CEW introduced its College Payoff Report in 2011. They established that, on average, higher education pays off with substantially higher lifetime earnings than those without college credentials. It has been a mainstay support in the argument over higher education value. Why then the growing skepticism, did they get it right?

Read on to find out.

“Aggregate statistics can sometimes mask important information.”

Ben Bernanke

Imagine deciding whether to go to college, and someone hands you a report saying it’ll earn you nearly a million dollars more over your lifetime. Sounds pretty convincing, right?

That’s precisely what the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW) claims in its 2011 report, The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings.1

But here’s the thing: that huge number might not tell the whole story. The CEW made some choices in how they calculated it. In this critique, we’ll dig into those choices, explain why they matter, and see if the premium holds up.

Ready? Let’s start by introducing the CEW and its report.

Introduction to the CEW and the “College Payoff” Report

The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW),2 established in 2008, is a highly regarded, nonpartisan research institute dedicated to exploring the intersections of education, labor markets, and economic opportunity.

Through its data-driven analyses, CEW provides valuable insights for individuals, educators, and policymakers seeking to understand how education translates into career success. Its work is widely respected and frequently informs policy debates at both state and national levels

Among CEW’s most impactful contributions is the 2011 report, The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings, authored by Anthony P. Carnevale, Stephen J. Rose, and Ban Cheah. (1) Since its release, this report has emerged as a pivotal resource in discussions about the economic benefits of higher education. It is often cited for its bold claim that a bachelor’s degree delivers a median lifetime earnings premium of $1.2 million, or 74%, compared to a high school diploma.

This striking figure has resonated widely, shaping the decisions of students, families, and policymakers who view college as a critical investment in future prosperity.

The college wage premium is central to the report’s argument. It is a key metric calculated using median lifetime earnings data from the 2007-2009 American Community Survey.

Definition of the college wage premium?

The college wage premium is a fancy way of saying “how much extra money you make by attending college.” It’s the difference in earnings between college grads and high school grads. It is published in three different versions:

- The college wage premium is expressed as a percentage advantage. The Federal Reserve estimated the college wage premium to be 75% in 2022. That means the median college graduate earned 75% more than the median high school graduate.

- The college wage premium is expressed as an absolute dollar advantage. If college graduates earn $52,000 annually, while workers with high school diplomas but no higher education credentials earn only $30,000, the college wage premium is $22,000 annually.

- The college wage premium is the absolute dollar earned over a lifetime. College graduates, on average, make $1.2 million more over their lifetimes.

The CEW focuses on the lifetime version, adding up what people earn over 40 years, from ages 25 to 64. Using “median” earnings (the middle amount, not the average), in a more recent update to their report, they say college grads make $2,268,000, while high school grads make $1,304,000. Subtract those, and you get the lower but still significant $964,000 premium, meaning college grads earn 74% more than a high school graduate with no additional education.

This premium is positioned as clear evidence of the college’s financial payoff. However, a closer look at these metrics reveals significant flaws in their calculation and interpretation.

Where could the CEW improve?

In evaluating college degrees using the college wage premium, the CEW makes four study assumptions that need reconsideration:

- Omitting Earnings and Costs before Age 25.

- Excluding Educational Costs.

- Failing to reflect the impact of taxes on earnings.

- Ignoring the time value of money.

Let’s explore each in more detail.

Omitting Earnings and Costs Before age 25

The CEW’s approach to evaluating college degrees using the college wage premium is as follows: ‘Synthetic estimates of work-life earnings are created by using the working population’s 1-year annual earnings and summing their age-specific average earnings for people ages 25 to 64 years. The resulting totals represent what individuals with the same educational level could expect to earn, on average, in today’s dollars, during a hypothetical 40-year working life.’

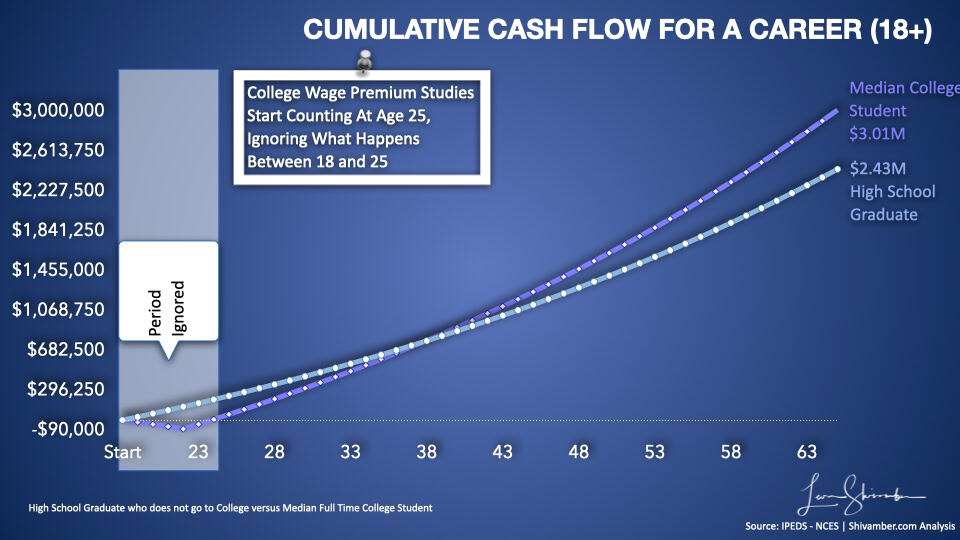

When comparing college graduates to high school graduates, the point of departure in these options is when they both graduate high school. The college student goes to College, while the high school graduate goes to work.

In starting their comparison at 25 years, the CEW ignores the period when the high school graduate accumulates a significant advantage. They do not incur any college costs and are earning a salary.

We use different sources and methodologies to create our synthetic lifetime earnings. In our model, adding the period between 18 and 25 years, the High School Graduate earns $130k during the four years our college student attends college.

Excluding Educational Costs

The CEW acknowledges college costs but minimizes their relevance, citing financial aid and variable pricing. Yet, this dismissal underestimates the financial burden borne by students and families.

The College Board (2023) reports a median net cost (after aid) of $14,000 annually for public four-year institutions. With only 44% of students completing degrees in four years (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022) and a median time-to-degree of 52 months, total costs often exceed $70,000.

For many households, these expenditures displace other investments. Federal Reserve data (2022) reveal that 46% of U.S. households lack retirement savings; the median balance is $87,000 among those with savings. Diverting $14,000 annually to college funding thus represents a significant opportunity cost, unaccounted for in the CEW’s premium. Including these costs would further diminish the net economic benefit of a degree.

The cost of attending College reduces the earnings premium estimated for college graduates. It should not be ignored.

Failing to Reflect the Impact of Taxes

Our federal tax system is progressive, taxing higher incomes at a higher rate. Further, we pay college costs with after-tax dollars, and tax deductibility is limited in value and timing.

BLS data (2023) show a median annual salary of $32,500 for high school graduates, incurring approximately $3,500 in federal income taxes (12% bracket). For college graduates earning $56,700, taxes rise to $8,000 annually (22% bracket). Over 40 years, this translates to $140,000 versus $320,000 in taxes, respectively. It’s a $180,000 differential. That $180k incremental tax reduces the advantage a college graduate’s lifetime earnings have over the high school graduate.

Ignoring the Time Value of Money

In its technical appendix, the CEW acknowledges criticism about the approach, ignoring the time value of money.

They use an example to argue why their conclusion does not change. They choose a discount rate of 2.5% because this represents the real interest rate of long-term government bonds. They show:

"Thus, the $2,789,000 lifetime earnings of a Bachelor's degree holder has a current lump sum value of $1,712,000, which is 39 percent less than the simple adding up of yearly earnings. Using discounted values, the dollar gap between Bachelor's degree holders and high school graduates falls to $786,000 (from nearly $1.3 million)."

"Even with discounted dollars, workers with a Bachelor's degree today can expect to have lifetime earnings $593,000 higher than workers with only a high school diploma. Therefore, it is still worth the time and investment to obtain a college education.”

"For those interested in present discounted values, simply reducing each of these numbers by 39 percent will result in a satisfactory estimate."

The College Payoff: Education, Occupation, Lifetime Earnings (2011)

We have several issues with this view.

Their choice of a 2.5% discount rate belies the view that higher discount rates are applicable for lengthy and risky investments. The current government funding rate is 5.4%, while Parent Plus student loans are 8.05%.

Financial investments of this nature typically require discount rates ranging from 8 to 20%, depending on the risk.

A higher discount rate would lead to a steeper than 39% discount than they recommend for explorers. Still, the gap shrinks even if we use the 39% discount.

How Does the CEW Stack Up to Other Studies?

The CEW is confident that the College Degree delivers a significant premium, but other research says, “Not so fast!” Here’s what some other experts found:

Brookings Institution (2022): The premium depends on your major. Engineering grads might double their earnings (100%+ premium), but arts majors sometimes earn less than high school grads. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work.3

HEA Group (2023): Students at 25% of institutions earn below the median high school grade. That’s right. Some college degrees leave you worse off!4

These studies show the CEW’s number is too simple. When you graduate, your major field of study, school, and even the economy change the premium. For some, it’s enormous; for others, it’s tiny or negative. The CEW’s report skips this nuance.

A Better Measure

We built our model that fixes the CEW’s flaws. We’ll include everything they left out and see what happens.

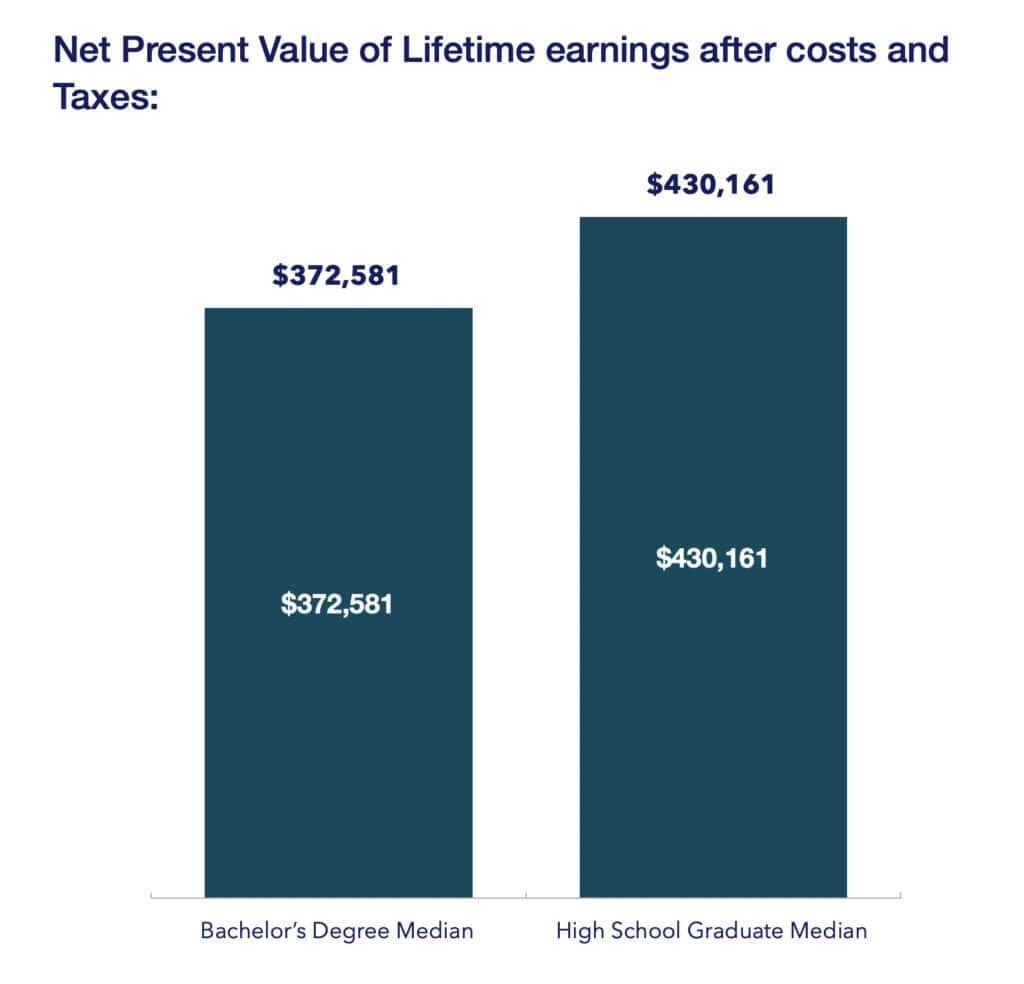

We start at age 18, include college costs, and pay attention to taxes and the time value of money. The result shows that the Net Present Value of Lifetime earnings (18 to 64) after costs and earnings for a Median High School Graduate, at $430,161, is higher than that of the Median College Degree, at $372,581.

The CEW College Payoff is misleading

The CEW’s $964,000 premium makes college sound like a no-brainer, but it’s built on shaky ground. Starting at age 25 ignores the head start high school grads get. Skipping college costs pretends tuition doesn’t hit your wallet. Ignoring taxes overestimates what you keep. Ignoring time value (using a zero discount rate) makes future earnings look more valuable than they are. The premium will drop or even turn negative depending on your numbers when we fix these.

Does this mean college is a scam? Not at all! It’s a game-changer for some, engineers or doctors can earn over $964,000 extra. However, the costs might outweigh the benefits for others, like arts majors or those at expensive schools. It’s not one-size-fits-all.

For you as a student, this means looking deeper. What’s your major? How much will you pay? What jobs can you get?

It’s a wake-up call for lawmakers: stop selling college as a guaranteed win with simplistic measures. Give students better data, like estimated lifetime earnings by major and school, so they can decide smartly. Incorporate tax and time value impacts in evaluating the differences between choices. The CEW’s report isn’t wrong; it’s just incomplete, and incomplete data can be misinterpreted and misleading. A fuller picture shows college can be worth it, but you must make the right choices!

Reference Sources

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Ban Cheah, and Emma Wenzinger. The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2021. cew.georgetown.edu/ collegepayoff2021.

- Carnevale, A. P., Cheah, B., & Rose, S. J. (2011). The College Payoff. Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2011 cew.georgetown.edu/

- Broady, Kristen, and Brad Hershbein. “Major Decisions: What Graduates Earn over Their Lifetimes.” Brookings.Edu. Brookings Institution, October 8, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/major-decisions-what-graduates-earn-over-their-lifetimes/.

- “Ensuring a Living Wage Through Higher Education.” Theheagroup.Com. The HEA Group, February 20, 2024. https://www.theheagroup.com/blog/ensuring-a-living-wage-through-higher-education.