Higher education is a big business, which we have shown is complex and often misunderstood by the participants.

History has shown that complex businesses without clear accountability for performance results can drive long-term bad choices.

These bad choices compound and often result in severe systemic shocks. Think real estate mortgage markets, disregard for risk, and the resultant catastrophic meltdown, which devoured many mainstream businesses.

Are current higher education policies likely to buy the next meltdown, this time among college investors?

Read on for an examination of the higher education industry as we explore the likelihood of economic meltdown. First, we will look at how prices work at Harvard, a uniquely endowed and successful institution. Then we explore how their approach might apply to the rest of higher education.

“Debt is a trap, especially student debt, which is enormous, far larger than credit card debt. It’s a trap for the rest of your life because the laws are designed so that you can’t get out of it.”

Noam Chomsky

- What Can We Learn From Harvard?

- Who is paying all these Harvard fees?

- How are prices set at Harvard?

- Are grants and scholarships driving Harvard Prices upward?

- How about the rest of higher education?

- Flat/Down Net Prices

- Someone pays the subsidies

- Are subsidies driving price increases in higher education?

- Parallels with Real Estate Debt Crisis

- Reference Sources

- Read More In This Series

What Can We Learn From Harvard?

Harvard College was founded in 1636 by Puritans. They wanted to have enough clergy for the new commonwealth.

It is the oldest institution of higher learning in the USA.

Today, it is considered one of the most prestigious universities in the world and still has a graduate divinity program.

Harvard Degrees are limited. Whether they are deliberately supply-constrained or a managed scarcity, enrollment grows at a marginal pace each year.

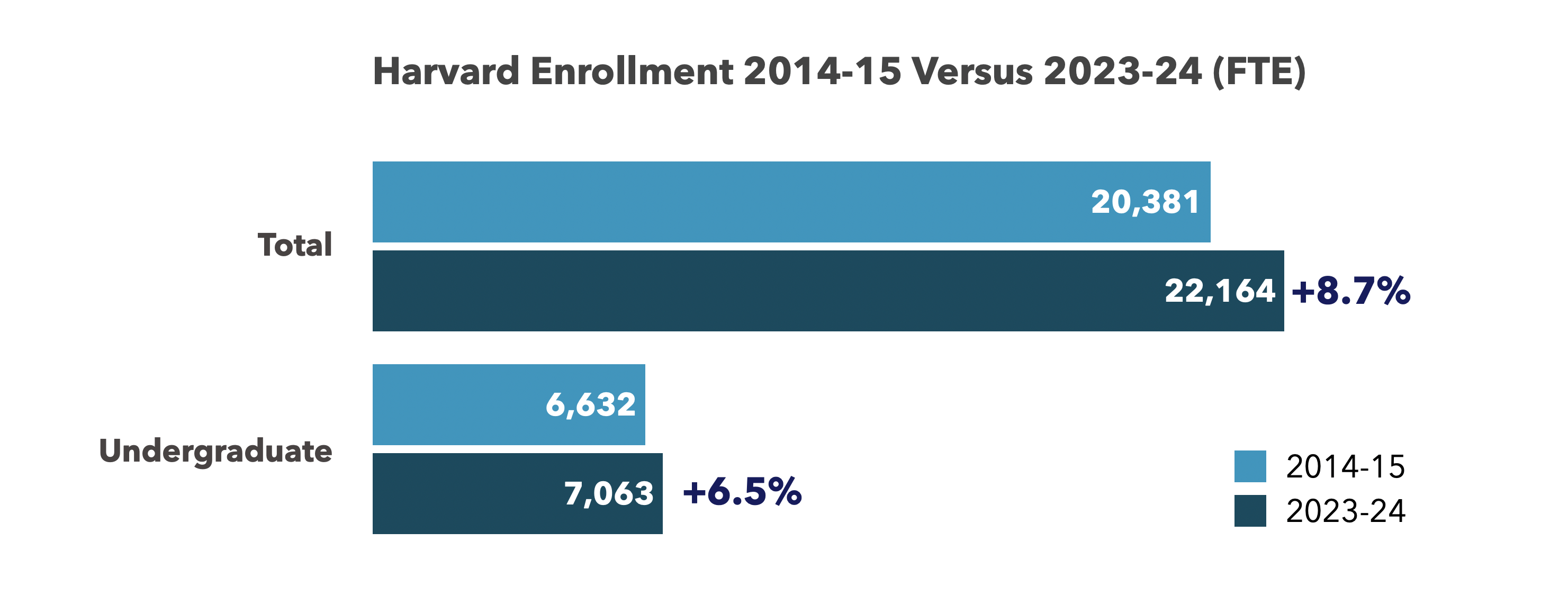

Between 2014 and 2024, the entire University grew enrollment by 8.7%, translating into a meager 0.87% growth per year. (1)

The undergraduate college grew at an even lower 0.63% per year.

Harvard degrees are eagerly coveted for several reasons:

- They are scarce (limited) and prestigious.

- Harvard is selective, so their incoming students are assumed to be high performers.

- It’s an impressive club to belong to for future networking.

- Most who enroll, graduate showing strong signals of intelligence, perseverance and social conformity.

- It’s a winning lottery ticket if you can get in. If you are academically excellent and of a lower income or from underrepresented communities, your degree could be fully funded at no out-of-pocket costs.

- On graduation, salaries are generally well above the national median, and many students will experience a great return on investment, even if society or their families’ returns are not so good.

Harvard undergraduate enrollment is so eagerly sought that wealthy parents will donate heavily or pay specialists large sums to increase their child’s chance of acceptance.

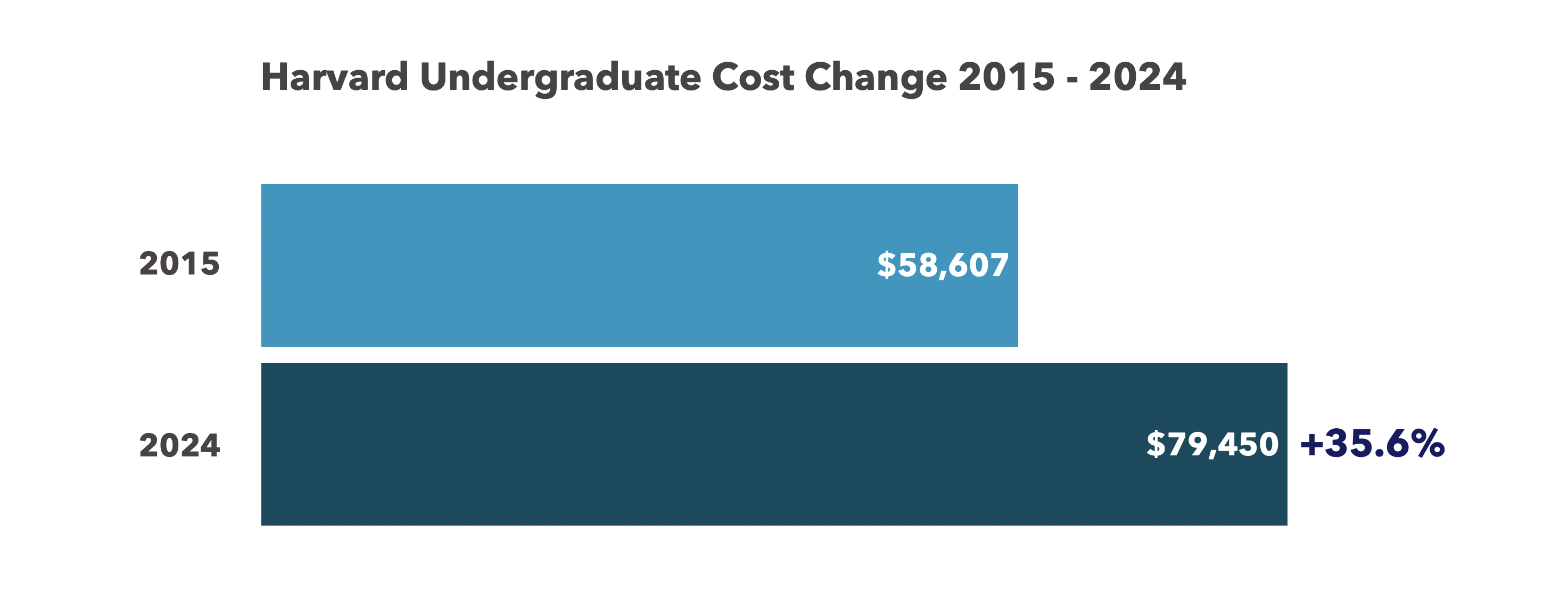

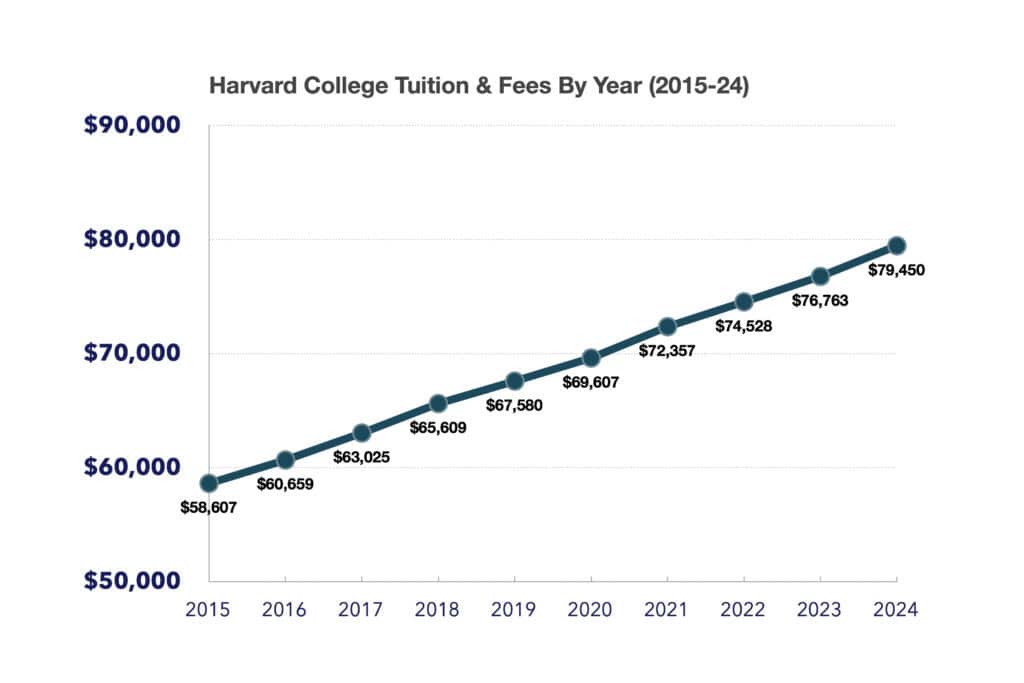

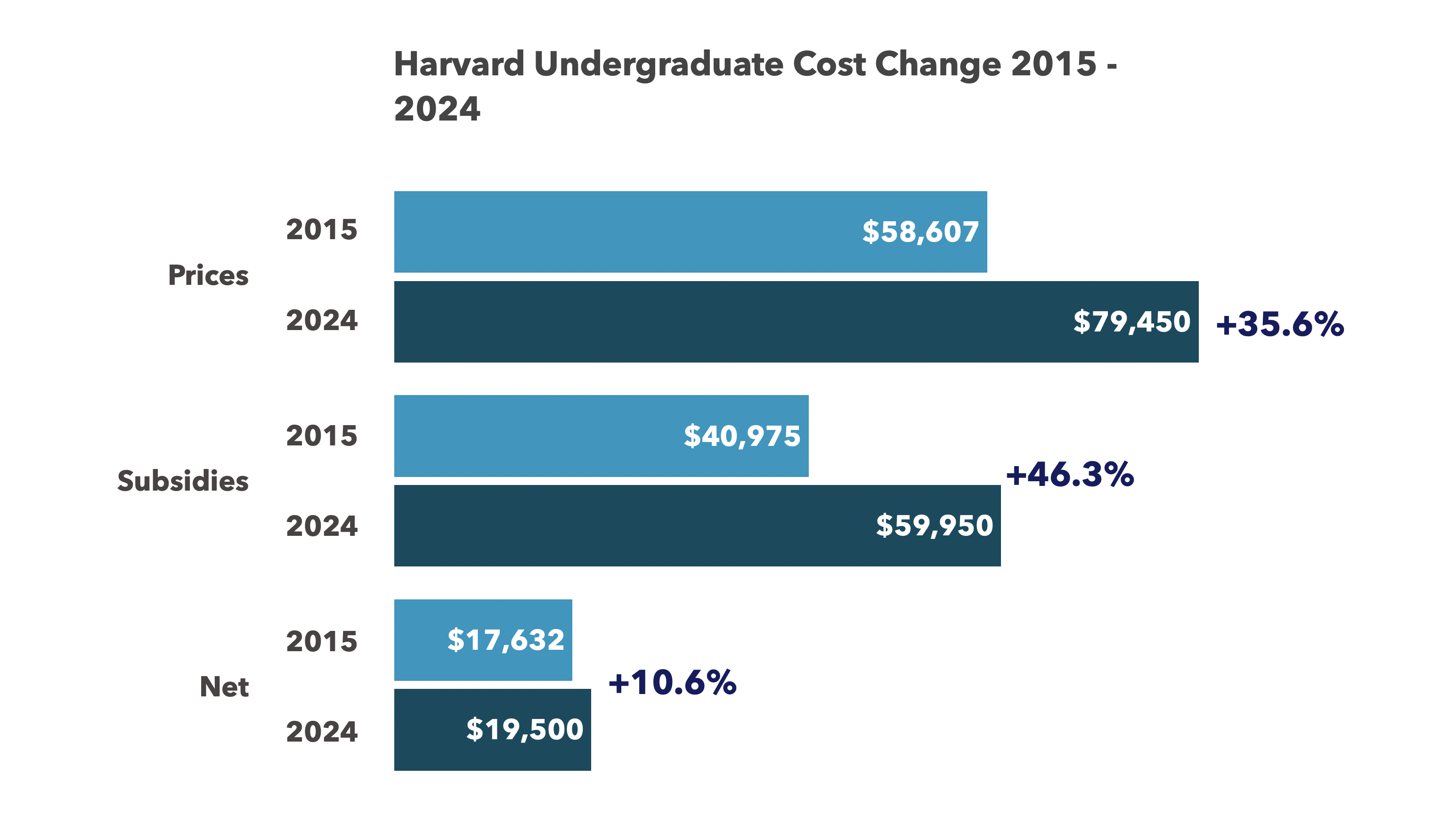

As one would expect, Harvard’s list price cost of attendance increased much more rapidly at 35.6% between 2015 and ’24.

However, only the wealthy families who pay the full cost experience those cost increases. The majority of Harvard undergraduates receive some award that reduces their out-of-pocket costs, which they are responsible for.

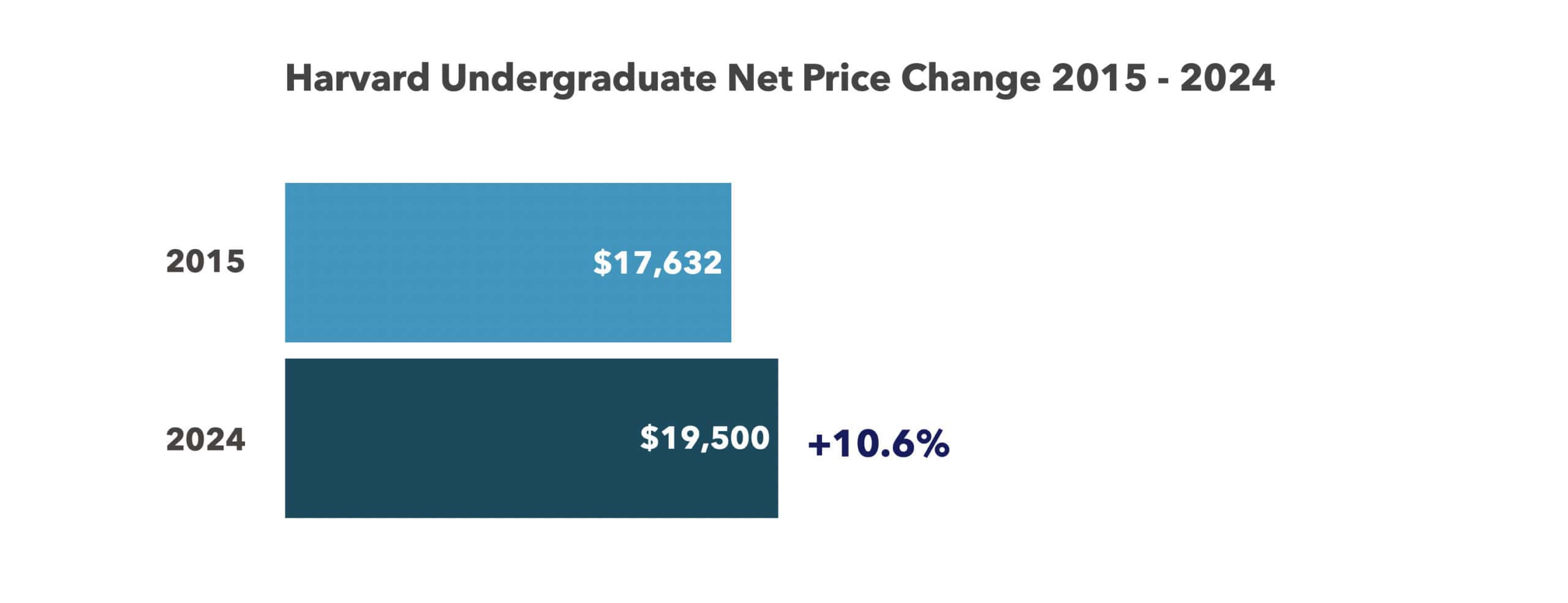

The out-of-pocket costs a student and family pay for attending college are the net price or net cost. These net costs vary by student and are affected by their academic performance and financial situation.

At Harvard, the Average Net Price in 2024 is a mere $19,500, which is well below the midpoint of all four-year colleges. It is 10.6% higher than it was in 2015.

While the cost of attendance is rising significantly (36%), the median price has not grown as fast (11%), keeping Harvard affordable for lower-income students and their families.

How does Harvard keep their net price low?

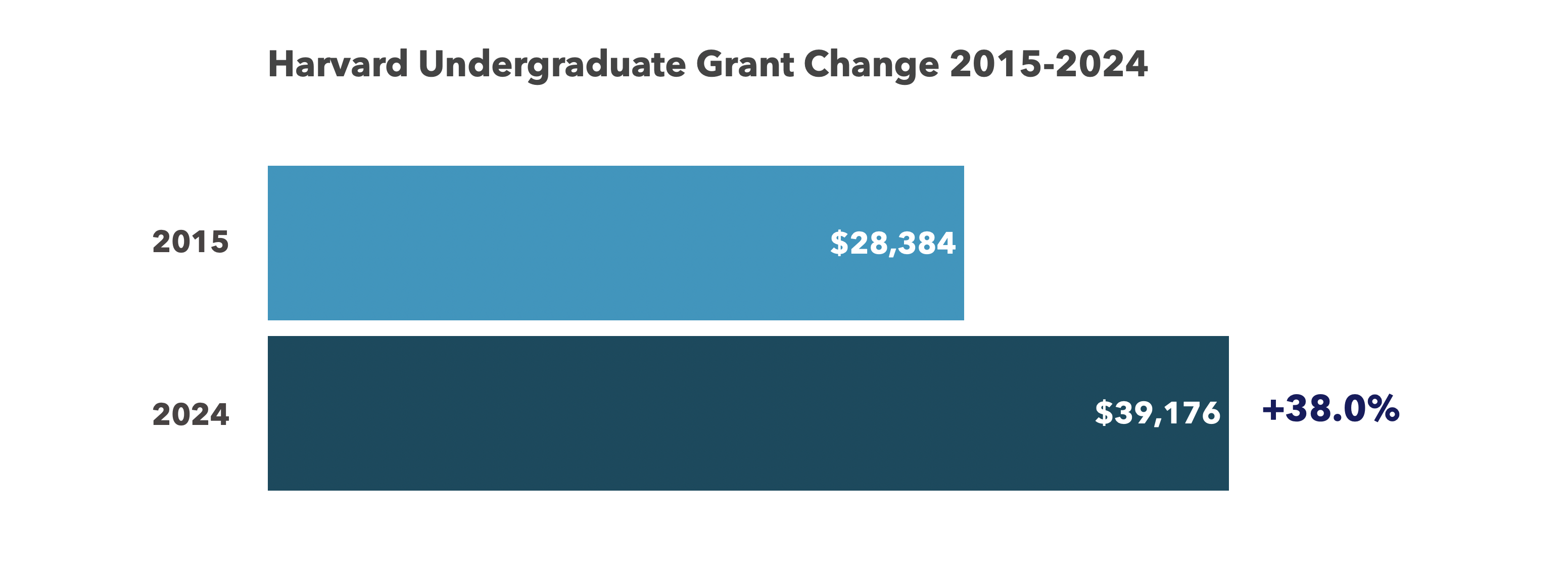

We start with the full cost of attendance (price list), which is reduced by scholarships and grants based on each student’s situation.

Scholarships and grants do not have to be repaid and drive real reductions in what the student or their family has to pay out of their own pocket.

Note that we don’t include loans in this calculation because loans do need to be repaid and are not a cost reduction but merely a shift in when those costs get paid.

As expected, Harvard and government grants that lower the net cost grew 38% over that time period.

If you are a lucky recipient of the highest level of grants, you can actually attend Harvard without incurring any of those out-of-pocket costs.

Your net cost in this case is zero.

But that does not mean Harvard gets nothing.

It implies that Harvard collected the full amount from another source. Someone else paid for you.

Who is paying all these Harvard fees?

About 50% of enrollment is made up of well-off families, and they will pay full prices, with some exceptions for academic excellence.

Others will pay less. The difference between what they pay and Harvard’s full Cost of Attendance is mainly made up by scholarships and grants, the biggest source being Harvard itself.

The Harvard endowment has existed for almost four centuries. It was started by John Harvard, a clergyman for whom the college was named, with 779 pounds sterling.

Many Harvard fans have added to the endowment over the years. Today, it’s in excess of $50 billion, the largest higher education endowment in the world.

The endowment is run by investment managers and generates a return based on the asset classes in which it is invested.

Each year, Harvard Endowment sets aside approximately 5% of the endowment’s value for use by the colleges.

That $2.5 billion is the largest contributor to Harvard scholarships and grants. Other sources include third-party scholarships funded by other donors and paid to Harvard, or the state and federal governments.

Students from low-income families, for example, may qualify for Federal Pell grants, and Harvard will collect that money from the federal government to reduce the student costs.

How are prices set at Harvard?

Like most large, successful institutions, setting prices is integral to the planning process. It is done at each college independently.

Enrollment plans are reviewed along with faculty and staff implications, driving infrastructure needs. Throw inflation and broader economic conditions into the stew.

When the process is completed, there’s a budget that lays out expectations for how the College will be financially run for the next year.

The budget is what Harvard expects to collect to cover the costs of that college. When divided by the number enrolled, the average cost of attendance is calculated.

The proposed price increases are submitted to the board, which typically approves them.

As with most large institutions, a lot of work is involved in setting budgets and getting to plans for enrollment and cost of attendance. However the results tend to feel much more like than a long term extrapolation that trends regularly ever upwards.

Harvard can increase prices each year because it’s popular.

It’s so desired that it does not have much problem filling its enrollment. Many of those enrollees will pay much higher prices to get their child enrolled here.

Harvard has a substantial endowment that allows it to discount its out-of-pocket costs to attract those it wants to attend.

Are grants and scholarships driving Harvard Prices upward?

Economists will recognize Harvard as a highly desired, supply-constrained product. Grants and scholarships are subsidies to the school that allow flexible pricing. Most will predict price increases when supply-constrained products are subsidized.

The large increase in subsidies did not result in a dramatic increase in enrollment (only 6.5% for the decade), and it also did not result in dramatic reductions in net prices.

In fact, net prices increased.

The chart shows Harvard College costs increased by approximately 36% in the decade, and because of the increase in subsidies and higher prices to families that could afford full price, it could still hold its average net price to a small increase of approximately 11%.

One could argue that the subsidies allowed Harvard to regularly float its prices up while giving it lots of flexibility to tailor pricing to support a strategy of seeming affordable.

Harvard is among a small group of elite institutions with enormous financial flexibility due to its large endowment. For these elite schools, price increases appear to be a strategy aimed at collecting more from a willing-paying segment of the wealthy and then funding large subsidies to attract candidates who can afford less but are academically excellent.

For these institutions, most of which appear to be supply-constrained and significantly limiting enrollment growth, they can grow their prices fully confident that the combination of higher revenues from the well-off and higher subsidies can allow them to continue to look affordable.

But is that true for the less than elite? Are subsidies contributing to price increases in the rest of higher education?

How about the rest of higher education?

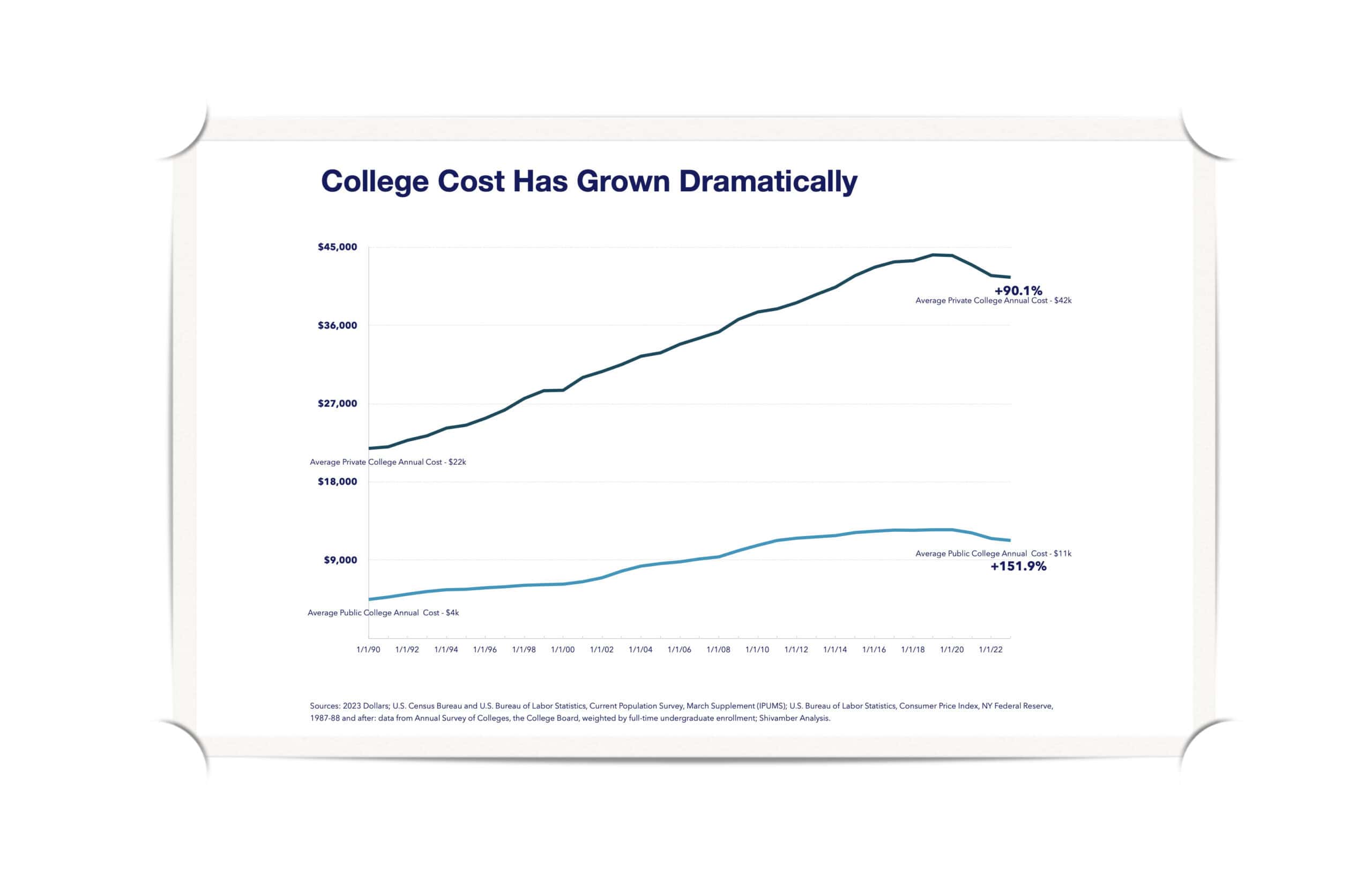

The attached chart shows the dramatic rise in average college prices since 1990. When adjusted for inflation, average public college costs have increased by 152%, and in private colleges, by 90%.

Absolute price increases have been much higher at 586% and 445%.

The astute reader might notice the recent decline in those costs, which are measured in 2023 dollars. That could be misleading, as college prices have continued to increase, although more slowly than inflation.

The relative decline is mostly there because inflation in 2023 is so much higher than in recent years, so college prices appear to have declined.

Further, in 2020, many colleges implemented freezes in tuition and fees due to the pandemic, which have been extended into 2023.

A small number of colleges have implemented price resets, where they have implemented price reductions.

It’s generally accurate to say that college prices have been rising for a long time and continue to do so. Recent price increases have been below the rate of increase that is inflation, but historically, they have been much higher than inflation.

Advocates argue that the sticker price is not that relevant, we should instead look at net costs. Net costs they argue represents what students and their families actually pay.

Let’s explore that perspective.

Flat/Down Net Prices

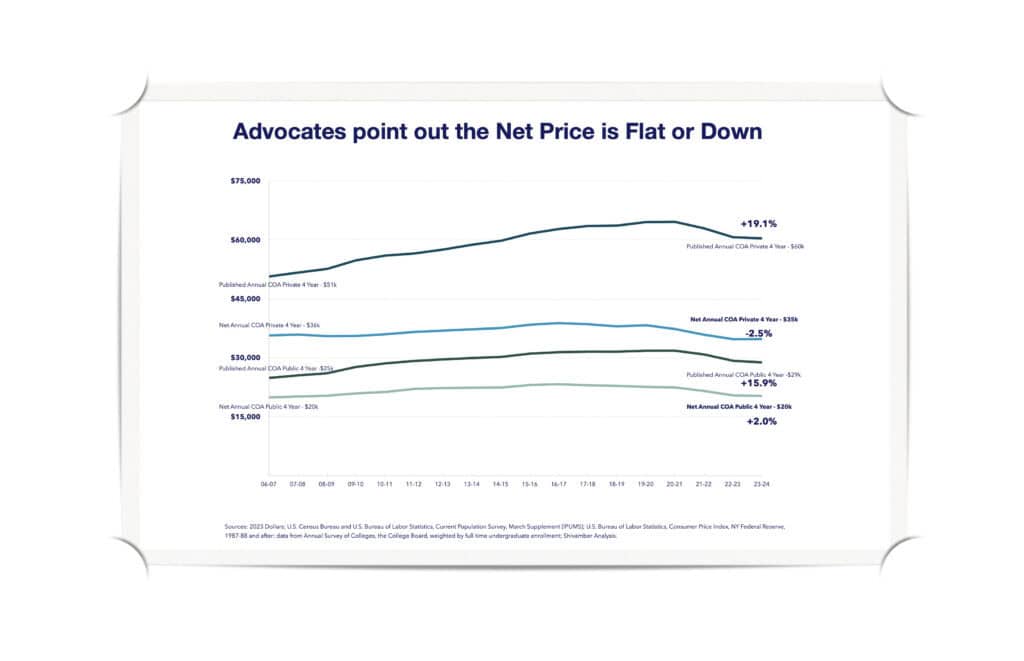

Looking at the attached chart, you will find the argument advocates make about Net Price being flat or down.

Private 4-year Average Cost of Attendance increased 19.1% between 2006 and 2024, yet Average Net Cost showed a 2.5% decline. Public institutions show a similar trend, although slightly up (2%) over the same period.

Again, keep in mind these are inflation-adjusted measures, so we still have the high 2023 inflation impact of showing a decline.

Nevertheless, given the large discrepancy between the change in Net and Published Price, we can agree that Net Price has not changed very much.

Published Costs or sticker price are the all in total costs expected to attend an institution.

Families with about $250k annual income and $250k assets are likely to pay the full costs. For all others, colleges will price-discriminate based on their interest in the particular candidate.

A package based on financial needs and academic excellence will result in a lower net cost.

The Net costs reflect the out-of-pocket expenses paid by those receiving grants or scholarships.

Several higher education researchers and advocates suggest that, since most students generally pay much less for college than sticker prices, and net costs reflect the out-of-pocket costs generally paid, sticker prices are misleading. To understand affordability trends, policymakers should track net prices, not sticker prices.(3)(4)

We disagree. They are both very important.

Most students do not pay the full sticker price, and the net price varies for every student based on their circumstances. But, for a large segment of those enrolled, there is no aid, and they pay full price.

In 2019-2020, 26% of in-state public college students and 16% of students enrolled in private, nonprofit institutions paid the sticker price. (5)

Furthermore, a significantly large share receives small amounts of grant aid that would qualify as paying near full price. They are generally well off financially.

The fact that the well-off are paying full prices and low-income students are paying dramatically lower prices should not be assumed to be a fair system if it results in long-term instability.

The higher sticker prices paid for by the well off represent a social wealth redistribution by higher education that is used in many places as one contributor to subsidizing costs for lower-income families.

At what point do the higher prices paid represent a subpar investment for well-off families?

Our analysis suggests that only 11% of four-year institutions produce a return on investment greater than that of a high school graduate, when full costs are considered.

Someone pays the subsidies

Sticker prices matter because the difference between them and the net price represents a subsidy that someone is paying.

It’s great that many parents and their students will pay net prices that are dramatically lower. However, to get that net price, society has to chip in generally to make up the difference.

Subsidies come from the federal and state governments, donors who create scholarships or endowments, and institutions that redirect a portion of full-price fees paid by students.

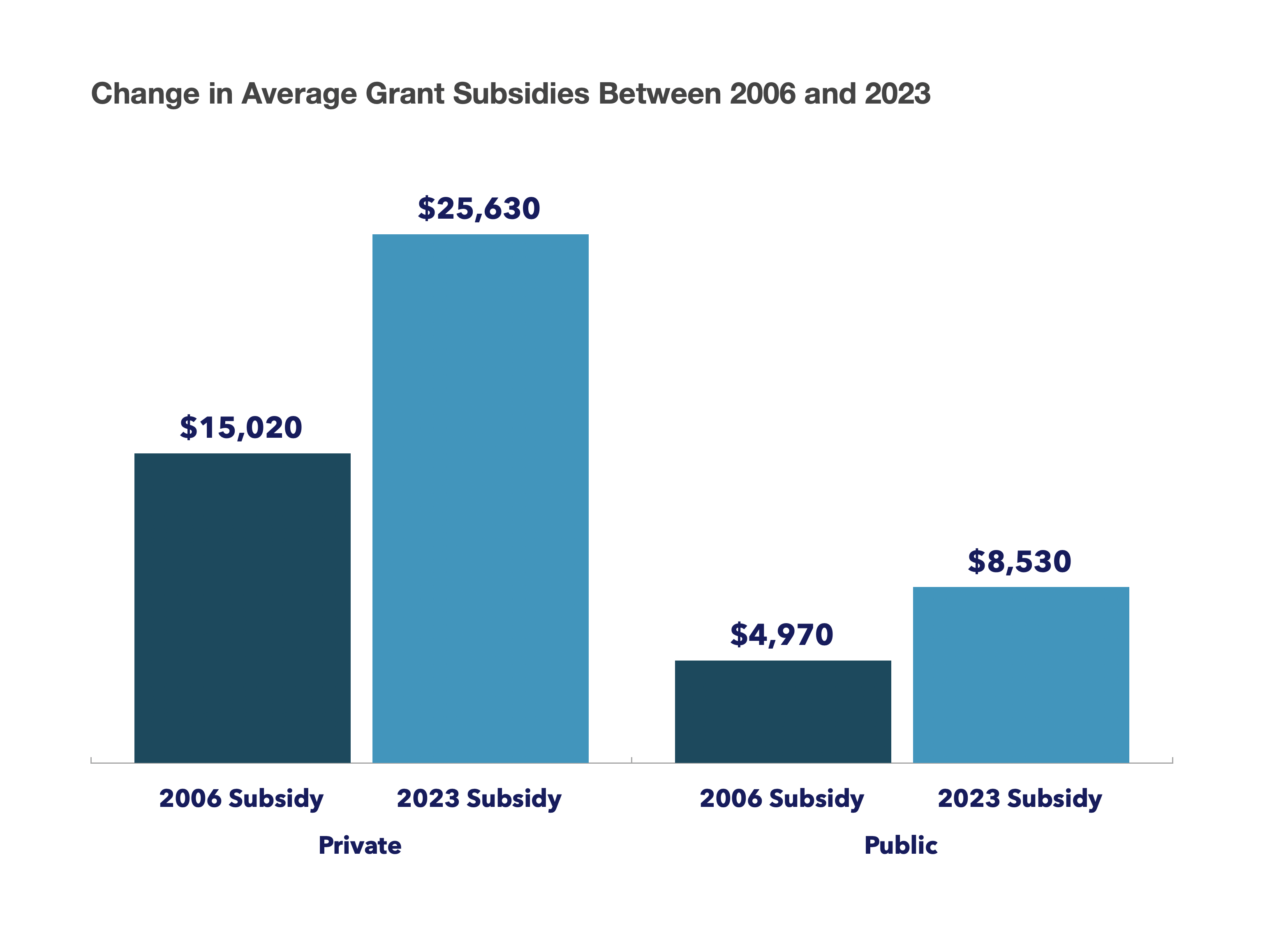

Between 2006 and 2023 Private Subsidies to reduce Sticker price grew 70.6% from $15k to near $26k. Public Colleges saw a similar 71.6% increase in subsidies.

Donors and taxpayers have increased their payments dramatically to keep net costs relatively flat.

How sustainable is this approach? Are subsidies contributing to higher sticker prices?

Are subsidies driving price increases in higher education?

In a 1987 New York Times op-ed titled “Our Greedy Colleges,” former Secretary of Education William Bennett wrote that “increases in financial aid in recent years have enabled colleges and universities blithely to raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase.”

Moreover, he added, “Federal student aid policies do not cause college price inflation, but there is little doubt that they help make it possible.”(6)

The Bennett Hypothesis is the name we use to represent the notion that subsidies broadly may have an unintended consequence of driving price increases in higher education.

The Congressional Research Service explored the Relationship between Federal Student Aid and Increases in College Prices in 2014.(7) Nine empirical studies had been published at the time using various metrics to isolate the effects.

The CRS survey did not find a high degree of consensus among the reports. However, the four studies that focused simply on list prices each found support for the Bennett Hypothesis.

A recent survey, The Bennett Hypothesis Turns 30, examined 25 studies. A majority found some effect of federal subsidies on the price of higher education in at least one segment of the higher education market. (8)

Our examination of the issue led us to review the rational goals and behavior of higher education administrators. We ended up agreeing with Bowen’s laws and their implications.

Howard Bowen was an American Economist. He is renowned for his book Social Responsibility of a Businessman, which is a foundation for today’s corporate Social responsibility (9). He was also President of Grinnell College, the University of Iowa, and Claremont Graduate University.

In 1980, Howard Bowen published The Costs of Higher Education, in which he posits a Revenue Theory of Costs, which is now known as Bowen’s laws:(10)

- “The dominant goals of institutions are educational excellence, prestige, and influence;

- There is virtually no limit to the amount of money an institution could spend for seemingly fruitful educational ends;

- Each institution raises all the money it can;

- Each institution spends all it raises;

The core idea behind Bowen’s theory is that university costs are primarily determined by available revenue rather than actual needs or efficiency considerations.

As universities raise more money, they tend to spend it all in pursuit of excellence and prestige, leading to a continuous upward spiral of revenues and costs.

We agree and see subsidies as a significant contributor.

Parallels with Real Estate Debt Crisis

We have experienced a Real Estate Debt Crisis and the ensuing meltdown as it unraveled. We are working towards a similar crisis and meltdown in Educational Debt today.

The real estate crisis and the current higher education debt crisis share some similarities but also have key differences:

The Similarities are striking:

- Unsustainable debt burdens: Both crises involve individuals taking on large amounts of debt that become difficult to repay.

- Government policies encouraging borrowing: In both cases, government policies promoted borrowing for homeownership and higher education.

- Impact on wealth building: Both crises hinder wealth accumulation, particularly for younger generations.

- Disproportionate impact on minorities: Both crises have had a more severe effect on minority communities.

There are some important and challenging differences:

- Market dynamics: The housing crisis was driven by speculation and loose lending, while the education crisis stems from systemic push for college enrollment, limited financial literacy around the value of college, rising costs, and flat wages.

- Nature of the asset: Homes are tangible assets that can appreciate, while education is an intangible investment.

- Discharge in bankruptcy: Unlike mortgage debt, student loan debt is extremely difficult to discharge in bankruptcy.

While the housing crisis triggered a global financial meltdown, the student debt crisis has been a more isolated, gradual, long-term economic drag.

However, the skepticism around higher education grows as the value does not materialize for many saddled with long-term debt and their families with diminished retirement accounts.

While both crises involve excessive debt burdens, the student loan crisis is more deeply rooted in structural issues around valuing higher education, education costs, and labor market returns, making it a complex, long-term challenge.

Addressing the student debt crisis will require policy changes around education funding and debt forgiveness.

The entire higher education ecosystem of students, parents, donors, institutions, and governments will have to face the need for better financial literacy around higher education investments.

This will improve as there is more institutional transparency and accountability in performance.

Or else, prepare for the educational debt meltdown!

Reference Sources

- Harvard University Office of Institutional Research & Analytics. “Fact Book: Student Enrollment.” Oira.Harvard.Edu. February 23, 2024. https://oira.harvard.edu/factbook/fact-book-enrollment/.

- College Board and National Merit Scholarship Corporation. ”Trends in College Pricing 2023.” Research.Collegeboard.Org. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://research.collegeboard.org/trends/college-pricing/highlights.

- Georgetown University The Feed. ”Still following College Sticker Prices? Ignore Them, Report Says.” Feed.Georgetown.Edu. April 26, 2024. https://feed.georgetown.edu/access-affordability/still-following-college-sticker-prices-ignore-them-report-says/.

- Levine, Phillip. “College Prices Aren’T Skyrocketing—But They’Re Still Too High for Some.” Brookings.Edu. The Brookings Institution, April 24, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/college-prices-arent-skyrocketing-but-theyre-still-too-high-for-some/.

- Levine, Phillip. “Ignore the Sticker Price: How Have College Prices Really Changed?” Brookings.Edu. The Brookings Institution, April 12, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/ignore-the-sticker-price-how-have-college-prices-really-changed/.

- Bennett, William J. “Our Greedy Colleges.” Nytimes.Com. The New York Times, February 18, 1987. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/18/opinion/our-greedy-colleges.html.

- Stoll, Adam, Shannon M. Mahan, and David H. Bradley. “Overview of the Relationship between Federal Student Aid and Increases in College Prices.” Crsreports.Congress.Gov. Congressional Research Service, August 22, 2014. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R43692/4.

- Robinson, Jenna A. Ph.D. “The Bennett Hypothesis Turns 30.” Jamesgmartin.Center. The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, December 1, 2017. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED588382.pdf.

- Caulkins, Doug. “President Howard Bowen & Corporate Social Responsibility.” Grinnell.Edu. Grinnell College, December 20, 2013. https://www.grinnell.edu/news/president-howard-bowen-corporate-social-responsibility.

- Howard Bowen. (2024, August 28). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Bowen