US policymakers regularly criticize Europe’s Value-Added Tax (VAT) refund system, arguing it tilts trade dynamics in favor of European producers. European counterparts counter with a World Trade Organization (WTO) ruling that deems VAT refunds for exporters non-subsidies, suggesting compliance with global trade norms. Yet, does technical legality equate to equitable outcomes? Can the system lead to undesirable effects?

“The secret of life is honesty and fair dealing. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made.”

Groucho Marx

- Understanding VAT and Its Refund Mechanism

- Why the Debate Over VAT Refunds?

- The Mechanism: How VAT Refunds Warp Export Pricing

- The Dual Benefit: VAT Countries Win on Both Ends

- Why It Feels Unfair, Despite WTO Compliance

- The Bigger Picture: A Structural Advantage, Not a Subsidy

- Why doesn’t the USA use a VAT system?

- It’s not an export subsidy, but it is unfair

- Systems have specific advantages

- Economic Theories have caveats that matter

- Where do we go from here?

Let’s examine how VAT operates, its effects on domestic versus imported goods, and whether it structurally advantages VAT-based economies like Germany over non-VAT systems like the US. More importantly, let’s tackle how varying taxation systems affect outcomes versus a free market ideal.

A concise introduction follows for my American friends unfamiliar with VAT to help ground the discussion.

Understanding VAT and Its Refund Mechanism

To grasp how Value-Added Tax (VAT) operates, start by imagining a product’s lifecycle. Consider how it moves through various supply chain stages, from raw material supplier to manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer, and consumer. At each of these stages, value is added. VAT is a consumption tax levied on the incremental value at every point of the production and distribution process.

Sales taxes are consumption taxes like VAT, except they occur at a single stage, at the end of the chain.

What Is VAT?

VAT is a multi-stage tax. For example, a manufacturer pays VAT on the raw materials it buys (input tax) and then charges VAT when selling the finished product (output tax). The manufacturer can subtract the input tax from the output tax and remit the difference to the government.

Each business in the chain charges VAT on its sales and can deduct the VAT it pays on its purchases. This mechanism ensures that the tax burden falls on the end consumer, while intermediate businesses remit tax on the value they contribute.

Why Refunds Matter

Without refunds, VAT would stack taxes on taxes, inflating costs and distorting markets. Refunds prevent this cascade effect.

To clarify how VAT refunds work in practice and why they prevent double taxation, let’s illustrate this with a simplified example, assuming 19% VAT:

- A cheese producer sells to a store for €5 + €0.95 VAT = €5.95.

- The store pays €5.95, recording €0.95 as input tax.

- The store sells to consumers for €10 + €1.90 VAT = €11.90.

- The store remits €1.90 – €0.95 = €0.95 to the government.

The government collects €1.90 in total VAT, constituting 19% of the final value added to the supply chain. This demonstrates the system’s efficiency and fairness by preventing tax duplication. No party is taxed more than once on the same value.

VAT and Exports

VAT paid on inputs is refunded for exports, so goods leave the country tax-free. This ensures taxation occurs where consumption happens, not production. It’s a principle the WTO deems neutral, not a subsidy. In the export case, consumption occurs overseas, and the importing country decides what taxes to add, if any.

Key Takeaway: VAT taxes consumption efficiently, with refunds maintaining neutrality across borders. Like a relay race, each stage contributes once, counted only at the finish line, that is the consumer.

Why the Debate Over VAT Refunds?

There is nothing inherently wrong with the system described. Right?

On its face, VAT’s refund system appears well-intentioned and equitable, taxing consumption where it occurs, not production. But does this neutrality hold in practice?

When goods are exported, VAT paid on inputs is refunded, stripping domestic taxes from the price. A European car exported to the US carries no VAT. Its price reflects production costs alone, not the tax. This isn’t a subsidy; it’s a mechanism to avoid double taxation (VAT plus US Sales Tax).

The refund does not mean the manufacturer makes more money when the product is exported. They are merely getting back taxes they paid, assuming the product would be consumed locally.

The WTO says that’s not a handout. It’s not a subsidy to manufacturers. Technically, they’re right. But let’s explore how that rational system gives exporters a leg up against a lower-taxed non-VAT system and why the USA is left playing catch-up.

This isn’t about bending rules; it’s about how the rules themselves tilt the playing field. European producers sell cheaper overseas than at home, while American products face higher costs when entering Europe. Europe wins twice. Its companies thrive globally, and European governments cash in on imports.

The WTO might not call it unfair, but the numbers don’t lie. This system is a structural advantage for VAT markets, even if it’s not a technical violation. To be clear, it’s not the system that drives the unfairness. The relative difference in taxes and the fact that one partner does not use VAT create advantages.

The conceptual switch

At the heart of the debate is a conceptual switch that conveniently gets VAT countries to get it both ways.

VAT is a value-added tax on domestic consumption. It is collected at every stage where value is added.

However, all these value-added taxes are refunded when the product is exported. It’s no longer a value-added tax; it’s a consumption tax. The VAT economies want to leave it up to the country receiving the product, which adds little value when it’s completed, to receive the full taxes on all value-added.

Further, when products are imported, the VAT receiver wants to collect taxes on all the value created, even when little value is added. It’s no longer a Value-Added Tax; it’s a consumption tax.

VAT countries want to have it both ways.

The Mechanism: How VAT Refunds Warp Export Pricing

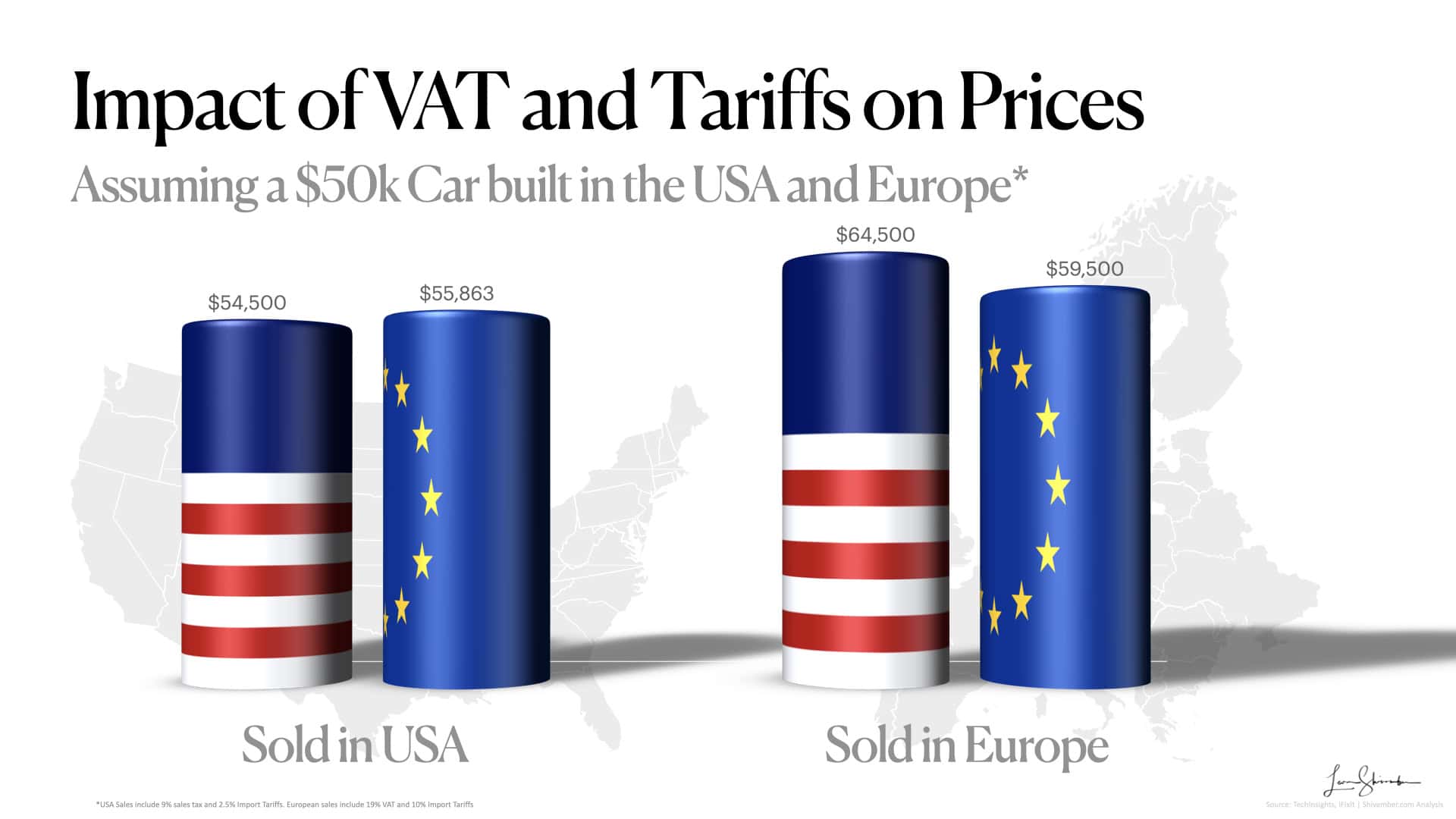

Using an example is the best way to illustrate how this all works. Let’s assume two cars with a $40,000 production cost, one from the USA and the other from Germany. We will consider a 20% gross margin at the higher end of industry norms for simplicity. That would mean they target base prices of $50,000 to cover their production, overhead, and profit.

Germany Domestic: In Germany, the German producer’s $50,000 will be sold to the consumer for $59,500 (assuming 19% VAT). The German Manufacturer gets $50,000, and the government collects $9,500 in VAT.

Germany to the USA: When the German producer ships that car to the USA, they must decide what value to use for landed cost. This varies depending on the company and how it wants to optimize its taxes on profits. In the interest of simplicity, we will ignore corporate tax optimization and assume that the producer has declared a landed value of $50,000. The USA will add a 2.5% trade tariff of $1,250. The consumer will have to pay about 9% in sales taxes on the subtotal of $51,250, adding another $4,613. The total price to consumers in the USA will be $55,863. It’s the same car but $3,637 (6%) lower than in Germany.

If you are American, I hear you saying, Wow, that’s great! The US consumer is getting a better deal than the German consumer. That’s because US pricing is closer to free market pricing than Germany. What could be wrong with that?

We need to examine the other side of the equation for that answer. Let’s examine American car sales.

USA Domestic: The American producer sells their car to local consumers for $54,500 ($50,000 plus the sales taxes of 9%, $4,500). This price is very close to the $55,863 from the German producer. The difference is the additional costs of the small tariff (2.5%). Sales tax is the same: 9%. VAT producers are correct in that the refund allows the German car to be priced competitively in the USA next to the US competitor.

USA to Germany: When exported to Germany, that car faces a 10% EU tariff, or $5,000. The 19% VAT on landed cost is added for another $9,500. This pushes the consumer price in Germany to around $64,500 ($10,000 or 18% higher than the USA). This price is higher than the $59,500 from the German producer. The difference is the more significant tariff (10%). VAT is the same, 19%. VAT producers are correct in that the VAT is applied equally.

The exact cost shows up differently to consumers due to VAT, taxes, and tariffs:

| Manufacturer Location | Price in Germany | Price in the USA |

|---|---|---|

| German Producer | $59,500 | $55,863 |

| American Producer | $64,500 | $54,500 |

German cars cost less in the US than at home, while US cars cost more in Germany, driven by tax and tariff disparities. This pricing flexibility may enhance German competitiveness abroad.

Because of tariffs, German consumers pay more for American cars than for German cars. Further, even though little value was added in Germany, the German government collected $9,500, whether it was an import or local consumption.

In America, the German manufacturer can claim that the US consumer is paying less than the Germans, despite the higher price than that of the US producer.

Even though we used an example with both cars starting at the exact cost, the German consumer assumes they are being offered a basic American car at a luxury price, while the American consumer experiences being offered a good German car at a bargain compared to German consumers.

It gets better for the strategists.

Not a bargain, it is a luxury

Consumers don’t care about how prices are constructed, whether there’s a sales or value-added tax, or the rationale for either.

They intuitively believe that if a product is shipped to another country, there are additional costs to get it there and make it available for sale, so they expect the price to be higher.

You can understand that the German producer does not want local consumers to complain that the same car is sold elsewhere at a discount. Worse, they don’t want the American consumer to think they are getting a bargain. That goes against the luxury positioning.

There is great interest in obfuscating price comparisons across markets. One of the best ways is to create different product models. In Germany, BMW offers the 318i as an affordable entry point, but in the USA, it’s the 330i, with a larger, more aggressive engine and luxury fittings. These additional costs increase the US product price to approximately the same level as in Germany for its entry model. In the USA, the entry model is positioned as a luxury offering.

The Dual Benefit: VAT Countries Win on Both Ends

This system doesn’t merely help VAT producers, it pads government coffers.

First, manufacturers can use VAT refunds to sell more cars overseas, boosting profits and securing jobs at home.

Second, when the American car rolls into Germany, the government imposes 19% VAT and a 10% tariff, pocketing about $14,500 per car (at a $50,000 landed cost). That’s revenue the German state keeps.

The USA doesn’t play the same game. Its 2.5% tariff on imported cars is peanuts compared to Europe’s tariff plus VAT. While Europe’s carmakers expand globally and its government collects additional taxes, American manufacturers struggle to compete, and the U.S. Treasury misses out on equivalent gains.

Why It Feels Unfair, Despite WTO Compliance

The WTO says VAT refunds are tax adjustments, not prohibited subsidies, because they are not direct financial contributions to producers. But fairness isn’t about legalese; it’s about outcomes.

Imagine a boxing match where one fighter gets to wear brass knuckles. Technically, it’s not against the rules if the refs allow it, but the other guy’s getting pummeled. That’s what this feels like.

European exports gain pricing power, while US exports face cost barriers, potentially skewing trade flows (e.g., Germany’s $85 billion US trade surplus in 2024).

The USA, relying on sales taxes and modest tariffs, can’t match that. Over time, this erodes American competitiveness. It’s not a level playing field, it’s a slope, and Europe’s standing at the top.

The Bigger Picture: A Structural Advantage, Not a Subsidy

This is not about individual products. Nor is it about whether the manufacturer receives a subsidy. It’s about economic architecture.

Want to make even more money and avoid USA tariffs? Set up assembly plants in the USA, take advantage of the lower assembly workers’ wages, and ship the high-value-added components from Germany without VAT. Those avoid tariffs.

Better yet, instead of shipping Continental/Michelin/Pirelli Tires from Germany, get them from Continental/Michelin/Pirelli USA. 50-70% of the content is raw materials(1) imported into Germany. The same tires can be manufactured in the USA. That simple shift reduces Germany’s export imbalance with the USA.

The benefits include the end-assembled product avoiding the USA 2.5% tariffs.

Along the way, you pick up some nationalistic American consumers who now think the car is built in America, so it’s American.

Germany’s VAT system is a cornerstone of its export-driven economy, helping it run a $300 billion trade surplus while the USA bleeds red ink.

American carmakers, battling foreign competition, are squeezed by a tax system exacerbating long-term vulnerabilities. Meanwhile, Germany’s playbook is, sell more abroad, deflate demand locally, tax imports at home. This strategy keeps its factories humming and its government coffers full.

The VAT system is a structural advantage that amplifies economic strength, while the USA’s tax setup exposes its industries.

Why doesn’t the USA use a VAT system?

Critics argue that the tilt is due to the USA’s use of sales tax rather than VAT, which most economies have moved to.

And they are right. If the USA introduced a VAT with the same parameters used by Germany, there would be no artificial tilting in favor of Germany.

Why hasn’t the USA embraced a VAT?

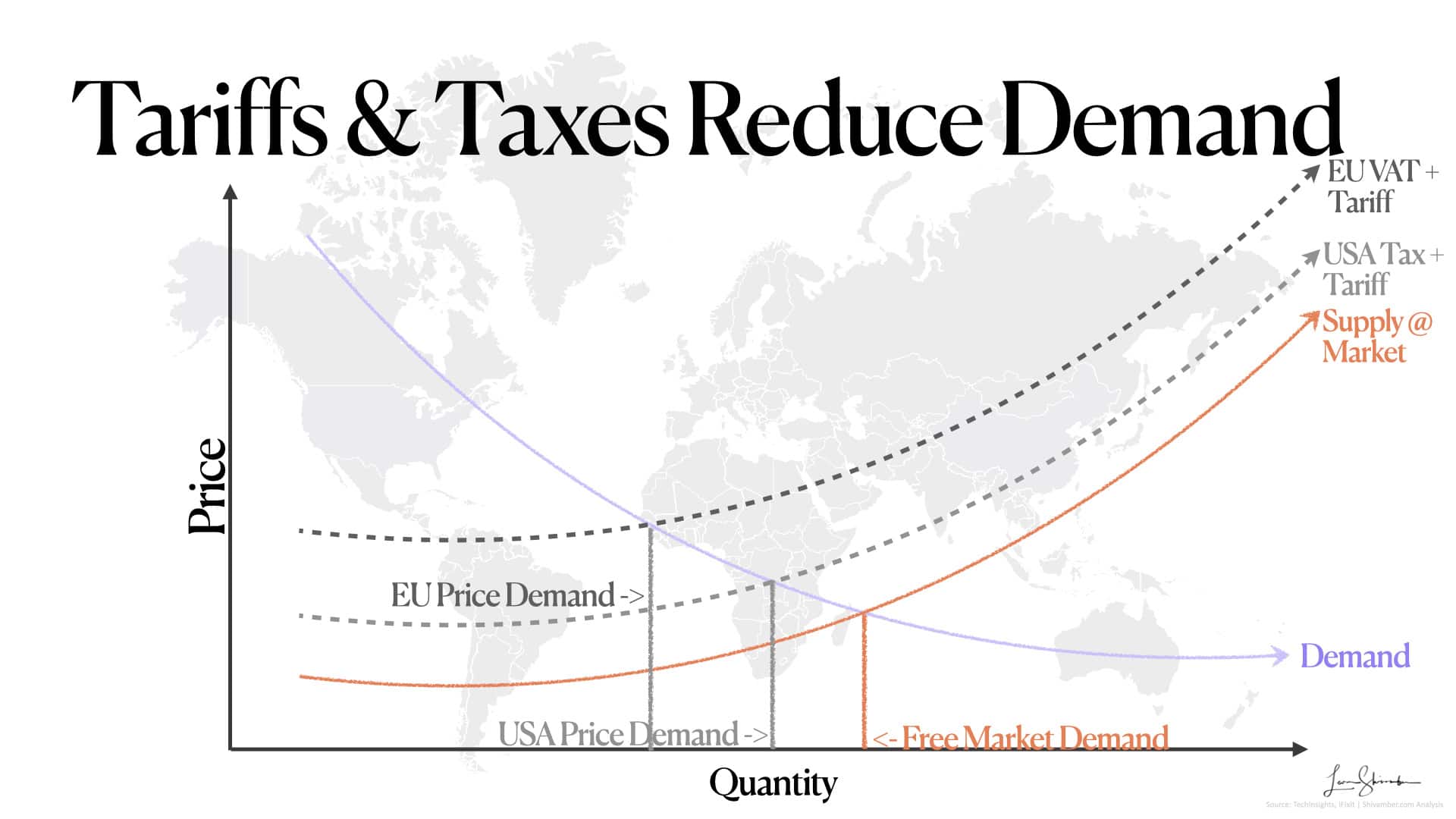

- VAT, like sales taxes, is regressive. They disproportionately impact lower-income households compared to higher-income ones. It takes up a higher portion of the low-income earnings. VAT countries may reduce the VAT rates for necessities and other essential goods, which helps reduce the burden. But the overall regressive nature remains. The higher the consumption tax, the more regressive it is. A VAT of 19% is far more regressive than, say, a 9% sales tax in a US municipality. Both are far from an ideal free market, but the higher VAT is worse.

- VAT, like sales taxes, reduces aggregate demand. Higher prices result in lower demand. The higher the prices are pushed artificially, the greater the reduction in free market equilibrium demand. A VAT of 19% reduces demand more than the 9% sales tax. Both are far from an ideal free market, but the higher VAT is worse.

- VAT, like sales taxes, is anti-savings. Critics argue that consumption taxes make savings more attractive. They do. However, they ignore that most savings are deferring consumption. We are not avoiding the tax; we are merely postponing it. The taxes mean less is available to save.

- VAT is associated with a bigger government and higher tax burdens. Conservative America opposes both.

Here is the paradox: despite the dysfunctional aspects of the trade comparisons shared earlier, adding a VAT in the USA would not change trade competition at the price level. Remember, the USA product shipped to Germany includes VAT. If the USA adds VAT, it will inflate the price of US products and imports by the same amount. The only difference adding a VAT makes is that the USA gets an additional boost to its tax collections. Like the VAT collectors, it could use the extra revenue to build infrastructure, reduce healthcare costs, and improve education, all benefiting producers. However, those benefits will take a long time to flow through the economy. The demand distortions would dwarf the benefits in the short term as we move further away from a free market.

Adding a VAT does not fix the trade distortions I have described. Indeed, such an action further shifts the USA from a free market ideal. Instead of requiring the USA to adopt a VAT to reduce the trading distortions between the USA and VAT economies, we should look for ways to minimize taxes. Wouldn’t that be better for consumers, trade, and growth?

It’s not an export subsidy, but it is unfair

When you hear someone defending the VAT refund with the answer that the WTO has deemed it legal and not an export subsidy, you will know the facts.

That technical legal argument does not contemplate the reality of the unfair advantage created. It’s not an export subsidy because the funds were not returned directly to the manufacturer for their use. But they did end up in the country!

The next time you see a European car cruising down the highway, remember: it’s more than European engineering that got it there, it’s European tax policy at work. The VAT refund system lets European companies sell cheaper overseas and increase the price of imports, giving its producers and government a one-two punch that the USA can’t match.

The WTO might call it fair, but the scoreboard says otherwise: Germany’s cars dominate U.S. roads, while American cars remain a niche in Europe. Policymakers must weigh these structural gaps, legal or not, as an economic reality. They create tilted playing fields.

Systems have specific advantages

When writing this, I was struck by the slight difference between fair and unfair, and how systems designed well to solve specific problems can lead to others.

Every system has tradeoffs. The VAT is a much better system than the sales tax used in the USA to reduce cheating and double taxation. It is also easier to implement politically, but more complex and challenging to administer.

I ran a simple trade simulation to examine what happens when five different strategies compete:

- Free of tariffs and taxes (close to the USA, but better)

- Import Tariffs of 20%

- Export Tax of 20%

- VAT of 20% on local sales and Imports, not on exports (Europe)

- VAT of 20% on local sales and Imports, not on exports, plus a 10% import tariff (like Europe on Autos)

The simulation assumed five economies of equal size with the same widget demand. Each country has a supplier producing the same widget at the exact cost. Supply chain cost effects and nationality preferences are ignored. The effective price in each market determines competitor unit sales, and we do it with high, medium, and low elasticity assumptions. We are looking for the equilibrium in sales due to the tariffs and taxes of the specific systems above.

The results?

Units Sold: The import tariff system always wins in units sold. The VAT Systems with an import tariff are second. The VAT without tariff and free trade are the same, and the export tax is far behind the others. This makes sense; import tariffs distort demand for the products that come in. The producer in that country gets domestic protection, yet is on a level playing field elsewhere, at least on unit pricing. The export tax makes your product less competitive elsewhere; it’s the biggest loser. It’s used when products are monopolistic, scarce, or controlled. The system that mimics the current European Automotive policy tilts unit sales in its favor because of the tariff.

Government Collections: The VAT plus Tariff combination significantly adds to the government coffers. Next was the VAT without tariffs. The import Tax alone was much lower, although higher than the Export tax alone. That is because the import tax was higher when the units sold came from an export tax market. Dead last, without any government collections, was the free trade system.

When we adjust country demand due to higher consumer prices (including tariffs and taxes), everyone sells less. Leadership positions do not change, and collections shrink.

As I pointed out earlier, the VAT system is not inherently unfair; it applies equally to competitors and local producers. However, it creates a hefty collection to add to government coffers, and pundits underestimate that impact.

A reputable UK organization provides a typical defense: “VAT raises £170bn, which is close to the cost of funding the NHS.” However, “The US does have national funded healthcare systems (Medicare, Medicaid, and Military and VA Programs) and, whilst they don’t provide the same breadth of coverage as the NHS, they cost US taxpayers almost the same (as a percent of GDP) as the NHS.” Thus, they argue that VAT collection is not an export subsidy.

This argument falls on its face. US healthcare costs far exceed those of anywhere else in the world. It’s approximately $14k per person in the USA versus $3k in the UK. Embedded in those costs are the disproportionate costs US consumers bear for research and development and subsidizing sales of life-saving treatments to low-income economies. More importantly, the US programs mentioned rarely cover the benefits of privately employed working Americans. They are aimed at retirees, people with disabilities, and government workers not involved in producing traded goods or services. The NHS covers production employees.

Rant: Smart people always use inappropriate comparisons to make their argument sound rational. In this case, they claim equivalency because taxation at 9% of GDP is used for healthcare in the USA and the UK. There are several problems with this line of thinking: Why is 9% an ok number? Is a number lower than 9%, or higher than 9%, better? What does the 9% have to say about the quality provided? Are they the same? And, finally, as pointed out earlier, with economies being different in GDP size and population, the proportion of GDP is almost meaningless.

VAT collections may not directly affect production costs, but they provide infrastructure and other benefits that improve the position of national producers.

Economic Theories have caveats that matter

Economists argue that systems are equal based on assumptions of neo-classical economics. That means: rational behavior, utility and profit maximization, full and relevant information, and market equilibrium. They take a lot for granted.

Imagine you’re studying international trade, and someone tells you:

“A tax on imports is the same as a tax on exports.”

Sounds odd. Right?

But that’s what Abba Lerner’s Symmetry Theorem shows. Under the right conditions, taxing what comes into a country (imports) has the same effect as taxing what goes out (exports).

What Does the Lerner Symmetry Theorem Say?

In 1936, economist Abba Lerner introduced this idea to explain a surprising truth:

If a country imposes a tariff on imports, it will impact the economy, like imposing a tax on exports, assuming a few ideal conditions.

Let’s break that down.

Similar Economic Effects

Whether a country taxes imports or exports:

Prices change: Import tariffs make foreign goods more expensive, and export taxes reduce local producers’ income from selling abroad.

Production shifts: Higher import prices encourage local production of those goods, while lower export prices discourage production for foreign markets.

Trade decreases: In both cases, fewer goods are traded internationally.

Efficiency drops: Resources are reallocated in ways that may not be optimal, leading to economic inefficiencies.

An essential element in driving the symmetry is the impact of foreign exchange rates. For Example:

Import Tariff Scenario:

A country imposes a 10% tariff on imports.

This raises the domestic price of imported goods, reducing demand for foreign currency (since fewer imports are purchased).

The domestic currency appreciates, making exports more expensive for foreign buyers (similar to an export tax).

Export Tax Scenario:

A country imposes a 10% tax on exports.

This reduces the profitability of exporting, lowering the supply of domestic currency in foreign exchange markets.

The domestic currency depreciates, making imports more expensive (similar to an import tariff).

In both cases, the exchange rate movement neutralizes the direct price distortion caused by the policy, leading to equivalent outcomes for trade volumes and resource allocation.

Even though the policies look different, they cause similar trade, production, and consumption disruptions.

Why Is It Called “Symmetry”?

The term “symmetry” means the effects mirror each other:

A tariff on imported clothes has the same impact as a tax on exported electronics, because both distort trade similarly.

It doesn’t matter which direction the tax is applied in; the net result for the domestic economy is the same.

What Conditions Need to Be Met?

This symmetry holds if the economy is simplified:

Only two countries and two goods. Think “country A trades wheat for cars with country B.”

No extra costs or trade imbalances. That means no shipping fees, deficits, or surpluses.

Perfect competition. Everyone’s a price taker with no monopolies or market power.

These conditions make isolating the effects of tariffs and taxes more straightforward, but ineffective in a more complex world. What happens if export taxes are intended to protect national assets, when import tariffs are placed to protect national security skills, or to fight a competitor that manipulates its currency?

Policymakers have to deal with the simplifications

The theorem suggests thoughtful analysis when applying trade policies, even in a simple competition. We should; there’s too much at stake. That’s not the point. We live in a far more complex world, leading to unpredictable results. We should not argue strategic moves because we are beholden to economic theories or political ideologies.

The simple models rarely consider the effects of currency manipulation, building third-country trans-shipment facilities to circumvent restrictions, or taking advantage of the rules. They infrequently consider behavioral aspects such as nationalism and the resulting distortion of consumer preferences. Finally, they underestimate the “anarchic view of the world” and the validity/importance of strategic choices where protectionism may result from national security needs.

Where do we go from here?

The USA’s (sales tax plus small tariff) competition with Europe’s (VAT plus larger tariff) situation has a current equilibrium level. In Autos, for example, there is a 7.5% European advantage. Removing those tariffs would benefit both economies.

The European VAT has an approximate 10% advantage over US sales taxes in government collections. The best response is not to match the VAT system. Adding a VAT system to capture that 10% differential in the USA moves us further away from a free market.

Reducing taxes, tariffs, and other trade-distorting frictions should bring everyone closer to the free market. That ideal benefits everyone.