Some of our most reputable economists work for the Federal Reserve. Their policy thinking broadly influences economic decision-making and ultimately affects consumers’ pocketbooks.

When the Federal Reserve weighs in on a topic, they do so with considerable heft and authority. However, trust in the Federal Reserve has wavered along political fault lines in recent years. Democrats are more trusting, Republicans and Independents less so. (1)

Talking about the Federal Reserve can get political quickly, but I would like you to remove any political hat you are wearing for this discussion.

Let me narrow down the trust question for you. Do you trust the Federal Reserve, particularly its research about what is best economically for the American public?

This article is part two of my exploration of the Federal Reserve’s published research. If you have not, you should read my first piece on the Federal Reserve Blind Spot: “The Damage When Smart People Miss Critical Insights? A $1.6 Trillion Blind Spot”

Would their recent research publication on the value of college degrees rehabilitate my previous disappointment?

Read on to find out what happened, and see if you agree.

“Whoever is careless with the truth in small matters cannot be trusted with important matters.”

Albert Einstein

- Background – Federal Reserve Updates College Value Research

- The $30,000 Myth: A Foundation Built on Quicksand

- Here’s what the Fed got wrong:

- Costs are artifically low

- Grants and Scholarships are too high

- Net costs are much higher than they assume

- Why Do Researchers Ignore Room and Board Costs?

- These cost exist specifically because of the college decision.

- The compounding error and Why this matters:

- The institutional inertial bias:

- Time Is Money: Graduation Isn’t Always On Schedule

- The Tax Trap: Ignoring Uncle Sam’s Cut

- The Problem of Averages – What’s your major?

- The Failure Rate Fiction: It’s Worse Than They Admit

- A Lens Problem, Not a Malicious One

- Beyond the Numbers: What Families Face

- What We Need From College ROI Models

- The Path Forward: Honest Analysis for Hard Choices

- Final Thought: When Precision Becomes Deception

- Reference Sources

Background – Federal Reserve Updates College Value Research

Those who follow me know that over the last decade, I have had a side project that evaluates college degrees as investments.

There has been so much skepticism lately, some of it well-founded, but many verging on the silliness that accompanies ideological beliefs.

One influencer and successful entrepreneur recently argued that all college degrees are scams. I’d like to know if he visits non-degree medical practitioners when he needs a diagnosis.

You can imagine my excitement when the Federal Reserve announced on April 8th this year that they would release Research on the Economic Value of a College Degree.

Finally, the preeminent economic researchers would weigh in on this consequential topic, with timely research.

The release would come on April 16th in two blog posts:

- The first, “Is College Still Worth It?” would determine whether the economic benefits of a college degree outweigh the costs for a typical graduate. (2)

- The second, “When College Might Not Be Worth It,” as they pointed out, looks beyond the typical graduate: those who pay higher costs, take longer to complete their degree, or have below-average earnings. (3)

Sure enough, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York researchers presented their definitive answer to the question, “Is College Still Worth It?”

An emphatic vote of confidence…

Their answer? A confident yes. But don’t stop reading yet. There’s a lot more to this story before we start celebrating.

They said college still delivers a strong return on investment, about 12.5% annually for the median student.

It reads like a comforting verdict in an era of rising tuition and mounting student debt.

…And a buried list of caveats

At the same time, those researchers offered a more sobering analysis in the second article, looking beyond the typical graduate. This time, they acknowledged that for 25% of graduates in the bottom earnings quartile, the return on college is just 2.6%.

The issue isn’t that either analysis is technically wrong. The problem is that they’re delivered as separate stories, without integration or sufficient reflection on what the divergence reveals.

The consequences of this split messaging are serious for families making once-in-a-lifetime decisions. When the good news is published in one article and the risk is buried in another, it encourages selective attention and reinforces optimistic biases.

They conclude emphatically that college is worth it, except in some atypical circumstances discussed elsewhere, if you are interested.

The impression they create is that the failures are not typical. We will examine this claim later.

For now, let’s focus on how they reached their conclusion.

The $30,000 Myth: A Foundation Built on Quicksand

The Fed’s analysis’s most glaring flaw is its cornerstone assumption: that four years of college cost just $30,000.

This isn’t a minor computational error; it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of what American families pay for higher education that undermines the 12.5% ROI claim.

Here’s what the Fed got wrong:

The researchers state that “the average net price of college, assuming it takes four years to earn a degree, totaled about $30,000 in 2024.” This figure is a staggering understatement.

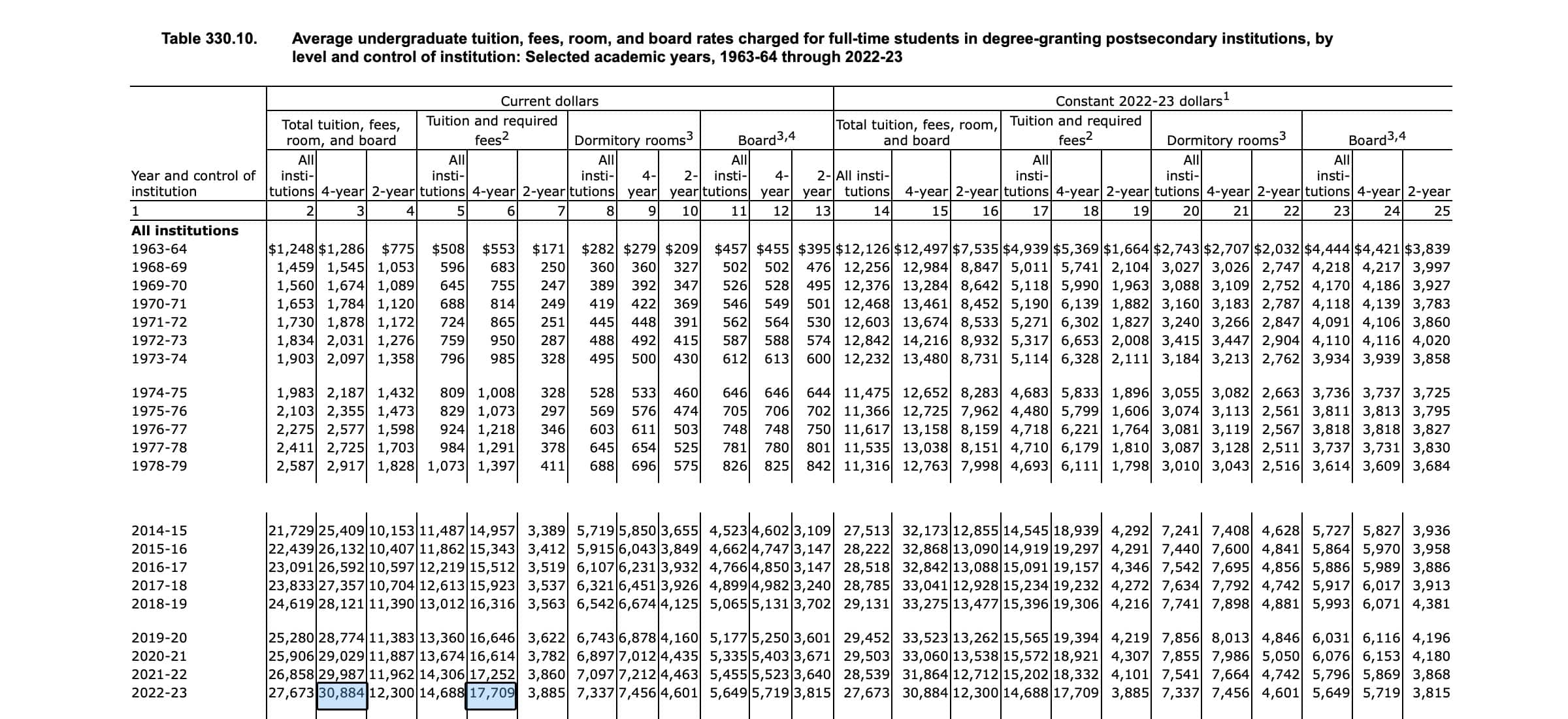

The authors determine the average out-of-pocket costs (around $21,000 in 2024) and then reduce this value by the average grant and aid received (around $15,000). They provide their sources: NCES (4) for the costs and the College Board (5) for the reductions to costs.

When considering costs, they ignore room and board, claiming those costs are incurred whether one attends college or not.

We disagree with this presumption.

It’s not inconsequential and certainly not atypical. Furthermore, it belies the opportunity for high school graduates who do not attend college to continue living at home at dramatically lower costs.

Costs are artifically low

Current data from the NCES shows the cost reality:

- Public four-year institutions: Average $9,750 per year tuition and fees, but $22,389 for tuition, fees, room, and board.

- Private nonprofit four-year institutions: The average tuition and fees are $35,248 per year, but the total costs include $49,654 for tuition, fees, room, and board.

- All institutions: The average tuition and fees are $17,709 per year, but the total costs, including room and board, are $30,884.

Grants and Scholarships are too high

The reductions for scholarships and grants are estimated at around $15,000, but they get this completely wrong.

Current data from the College Board Source they provided shows the error:

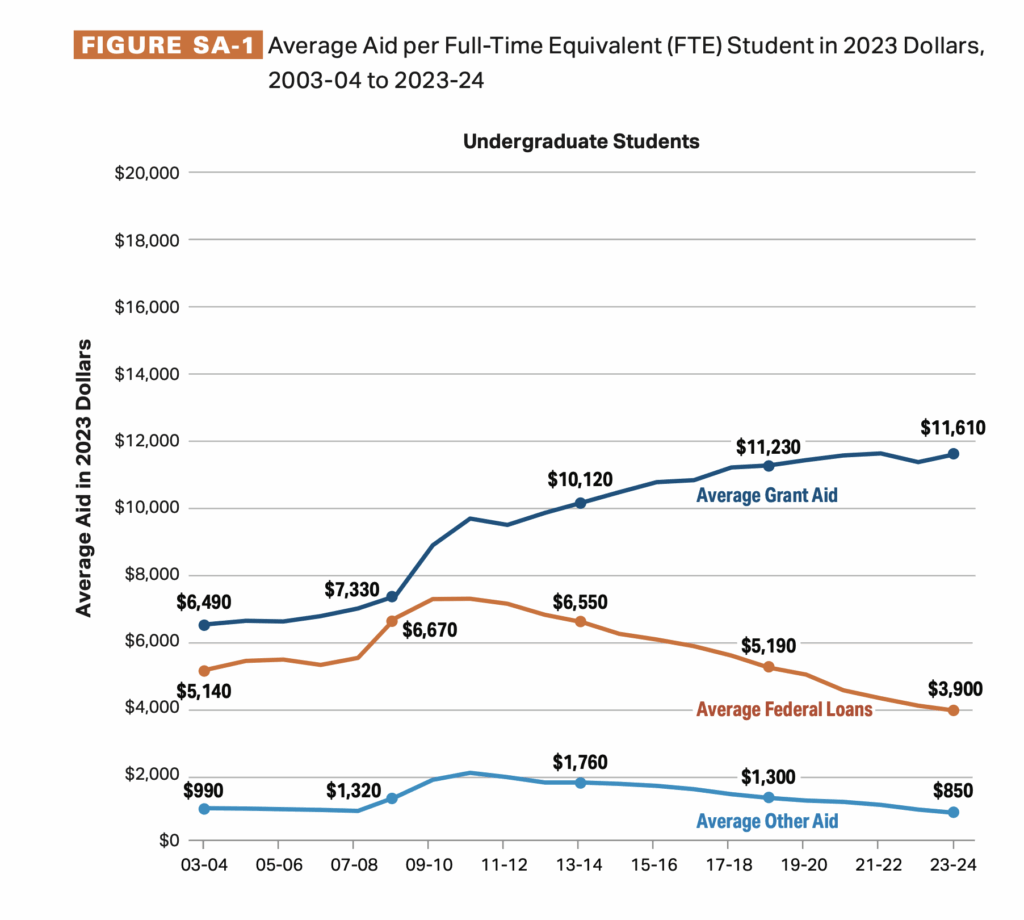

“In 2023-24, undergraduate students received an average of $16,360 per full-time equivalent (FTE) student in financial aid: $11,610 in grants, $3,900 in federal loans, $760 in education tax benefits, and $90 in FWS.” (6)

College Board Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2024

The College Board’s reductions include $3,900 of federal loans. These are not cost reductions; they are expensive, delayed payments. They should not be considered a reduction in costs.

When adjusted for this oversight, the average cost reduction due to grants should be $12,460, not $16,360 or the $15k mentioned by the Feds.

Net costs are much higher than they assume

Using the corrected numbers from these sources, we get annual and 4-year net costs of:

- Public four-year institutions: $9,929 per year and $39,716 over 4 years.

- Private nonprofit four-year institutions: $37,194 per year and $148,776 over 4 years.

- All institutions: $18,424 annually and $73,696 over 4 years.

The College Board reports that the researchers’ reference shows that the Net total Budget for four years at public four-year colleges ranges from $55k to $122k. For Private Institutions, that range is $62k to $232k.

The Fed’s $30,000 assumption isn’t just wrong; it’s bad for the average student by a factor of 1.8 to 7.7 times, depending on their unique financial situation and the institution they attend.

Why Do Researchers Ignore Room and Board Costs?

College return on investment (ROI) studies have a glaring blind spot that fundamentally distorts their conclusions about higher education’s value. While these analyses meticulously calculate tuition costs and post-graduation earnings, they systematically exclude room and board expenses, representing 44.5% of total costs at public four-year institutions and exceeding $53,000 over four years.

This exclusion isn’t merely an oversight; it’s a methodological flaw that renders most college ROI calculations misleading for the families who rely on them.

The traditional economic rationale is that “You Have to Live Somewhere.”

College ROI studies typically exclude room and board costs based on a simple economic principle: students must eat and live whether they attend college or work. One economic analysis explains, “Room and board would not be a cost since one must eat and live whether working or at school.”

This reasoning suggests that housing and food expenses represent basic living costs that occur regardless of educational choices.

Traditional economic analysis focuses on incremental costs, which exist solely because of the decision to attend college. Under this framework, only costs that wouldn’t exist in the counterfactual scenario (working instead of attending college) should be included in ROI calculations. This leads researchers to include tuition and fees while excluding room and board as “non-educational” expenses.

Many institutions favor this exclusion because it produces more favorable ROI calculations.

When the Federal Reserve estimated college costs at just $30,000 over four years, it essentially used a tuition-only model that made college appear dramatically more affordable and profitable than it was.

After all, the most significant costs were excluded, assuming they were the same whether attending college or not.

But are they?

The traditional economic argument that “students must live somewhere” fundamentally misunderstands how housing costs change when attending college. Young adults have significantly different housing options when working versus attending college:

In the Working Scenario, the High School Graduate:

- Can live with parents/family (typical for the 18-22 age group)

- Can choose lower-cost housing markets

- Can select housing based on income capacity

- Can share housing costs with multiple roommates

For the College Scenario, the student is:

- Often required to live on campus (especially freshmen)

- Tied to expensive college towns with inflated housing markets

- Limited housing options due to academic calendar constraints

- Subject to mandatory meal plans and housing requirements

Room and board costs have been rising faster than tuition in recent years. Between 2010 and 2020, housing costs rose 14% more than inflation, while tuition growth has slowed. This trend makes excluding these costs increasingly problematic for accurate ROI calculations.

The opportunity cost differential between these scenarios represents $13,310 annually at public institutions. The median is understated due to the significant portion of students who live at home.

These cost exist specifically because of the college decision.

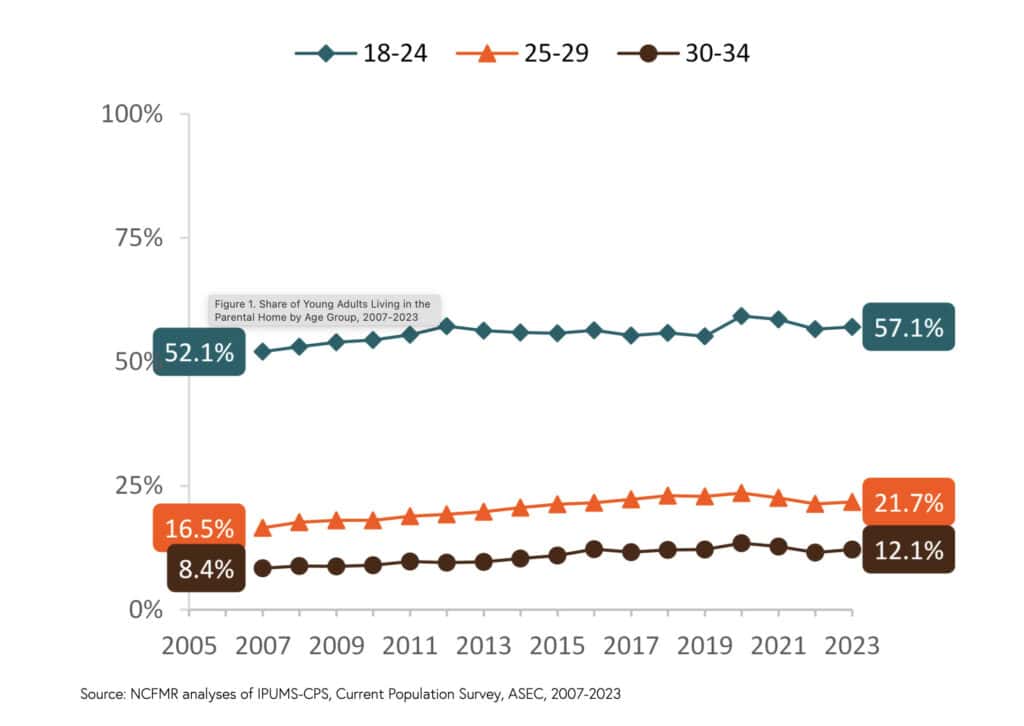

One final thought. Recent estimates show 57.1% of 18-24 year olds live at home with parents in 2023. (7) For those students, room and board are significantly lower than the mandatory costs paid when attending college.

The median incremental cost of an 18-24-year-old living at home is unlikely to approach those for room and board while attending college.

Assume for a minute that you have a child considering college. They could stay at home and go to college in town. Or they can attend another college out of state, which requires them to stay and pay for room and board. They may even need a car, which may not be necessary when living at home.

Let’s assume that both college choices have the same tuition and fees. Both are remarkably similar in that, historically, graduating students earn about the same amount. The only difference is that one costs less.

Do these choices deliver different investment returns? You bet they do.

Yet, the Fed researchers want you to ignore those incremental room and board costs when evaluating your college investment.

The simple reality is that college room and board are higher than alternatives and are directly related to college choice. Those who pay these bills know the truth.

They should be included in any investment analysis of college degrees.

The compounding error and Why this matters:

When the Fed explores alternative scenarios, it briefly tests a $85,000 total cost figure and finds that even this modest adjustment drops its median ROI from 12.5% to 10.1%.

Their sensitivity analysis shows costs of $112,000, dropping the ROI to 9.2%.

Why does this matter?

The Fed’s entire framework rests on this faulty foundation. Their confident 12.5% return crumbles when subjected to real-world cost data.

This isn’t a rounding error; it’s a methodological failure that renders their primary conclusion meaningless for the families relying on it.

It begs the question, what is typical? According to the Federal Reserve researcher, a typical college-going student and their family will incur an optimistically low cost of attendance.

The institutional inertial bias:

The Fed’s use of outdated, artificially low cost figures suggests an institutional reluctance to acknowledge the true scope of the college affordability crisis. Whether through data lag, methodological convenience, or wishful thinking, this assumption error transforms what should be a sobering analysis into false reassurance.

When your foundational assumption is off by 300-400%, everything built on top of it collapses. The Fed’s ROI calculation isn’t just imprecise, it’s fundamentally misleading.

Time Is Money: Graduation Isn’t Always On Schedule

The Fed’s second major flaw is assuming students graduate in exactly four years. Department of Education data tells a different story: (8)

Only 44% of students graduate in four years

56% do not graduate in four years

NCES – Department of Education – Fast Facts

Graduating within four years is not typical; it’s atypical.

That’s right. The typical college student is not described in the first article. They are more likely to be described in the second.

When the Fed adjusts its timeline from four to six years, even keeping its artificially low $30,000 cost baseline, the ROI drops from 12.5% to 7.1%. Combine graduation timelines with realistic costs, and the returns become even more sobering.

Extended timelines also carry hidden costs. Students who take five or six years to graduate face:

- Additional tuition and living expenses

- Delayed entry into the workforce

- Reduced lifetime earning potential

- Higher opportunity costs

Many students also experience career delays due to unpaid internships, graduate school preparation, or economic downturns, factors that don’t appear in the Fed’s neat four-year model but matter enormously to families planning their financial futures.

The Tax Trap: Ignoring Uncle Sam’s Cut

Perhaps most egregiously, the Fed calculates returns using pre-tax income while college is paid for with after-tax dollars. This isn’t a technical detail; it’s a fundamental misrepresentation of actual returns.

The math: College graduates typically face 22-24% marginal tax rates on their income premium. A $32,000 annual earnings advantage becomes roughly $24,000-$25,000 incremental take-home pay. Accounting for taxes reduces the Fed’s already-questionable returns by another 20-25%.

Real returns: Using the Fed’s methodology but adjusting for taxes:

- Their claimed 12.5% return becomes approximately 9.4%

- With realistic costs and timelines, actual returns drop to 3-6%

This isn’t a minor adjustment; it’s the difference between a “strong investment” and a marginal one.

The Problem of Averages – What’s your major?

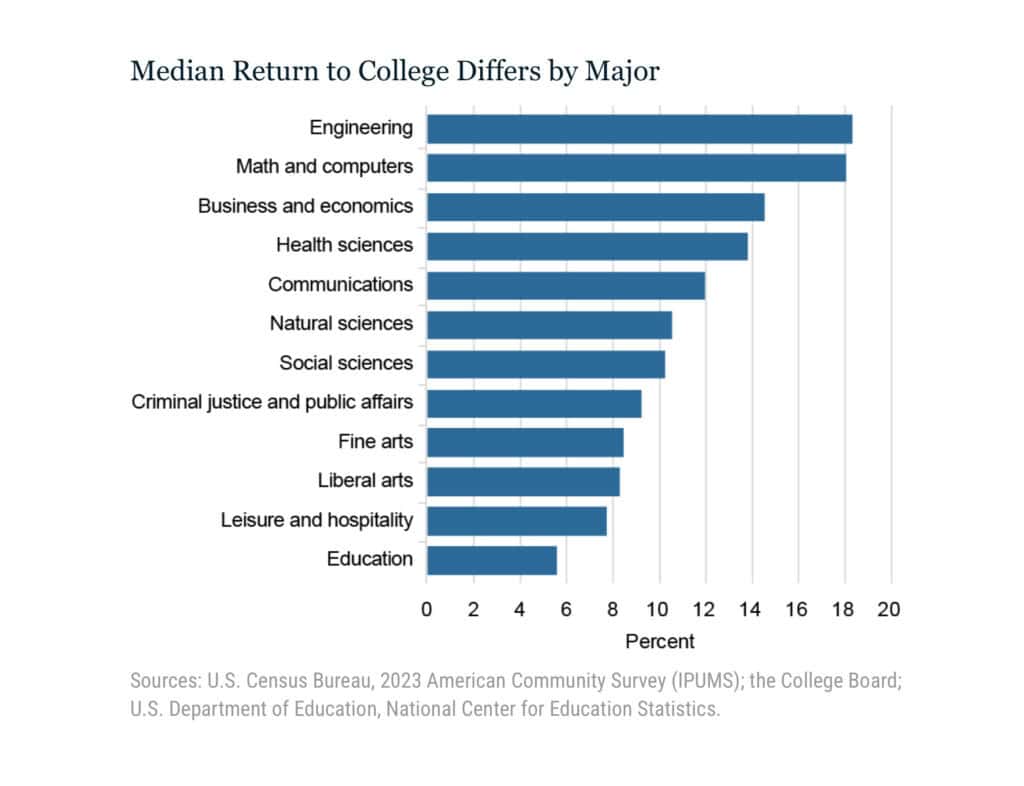

In their second article, the researchers look beyond the typical graduate and discuss the difference between College Majors.

They acknowledge a significant variation in the college degree ROI by select majors. While their overall ROI is estimated at 12.5% (using their methodology, which we consider inflated), an in-demand major like engineering, math, and computer science’s ROI is closer to 18%.

Fine arts, Liberal Arts, Leisure and Hospitality, Education range from around 8.5% to below 6%. That is before we make the corrections discussed above.

The typical college graduate does not study engineering, math, or computers. They study degrees with below-average ROI.

The Failure Rate Fiction: It’s Worse Than They Admit

The Fed estimates that 25% of graduates see returns of just 2.6%, a figure they describe as concerning but not catastrophic. However, this calculation relies on unrealistic cost assumptions.

- Using real-world cost data grounded in current tuition trends. Including room and board and more accurate grants reduces the ROI from 12.5% to between 9% and 10%.

- Adjusting for take-home pay, not just gross earnings, reduces the 9-10% to 7-8%.

- Accounting for longer time-to-degree as a standard outcome, not an edge case, reduces the 7-8% to 5-6%.

- Acknowledging variation by major and institution.. If some degrees generate ROI well below 12.5%, the above adjustments drive them even lower. For example, Liberal Arts at 8%, versus the 12.5% will now be closer to 0.5-1.5%.

- Including risk of non-completion and underemployment. Added all together, the typical college graduate is not as well off as the Federal Reserve researchers would have us believe.

The effective failure rate isn’t 25%. Our analysis suggests that more than half of the students would get better returns from alternative paths: vocational training, community college, or direct workforce entry.

This isn’t pessimism, it’s arithmetic. The Fed’s model systematically understates costs, overstates benefits, and ignores the financial realities facing American families.

A Lens Problem, Not a Malicious One

To be clear, this isn’t about accusing Fed researchers of deliberate deception. These are capable economists applying institutional frameworks they’ve refined over decades. The problem is that institutions, even sophisticated ones, develop blind spots.

The Federal Reserve has a vested interest in stability and optimism. Their research informs policy decisions that affect millions of lives. When their models suggest college is a “safe bet,” it supports broader economic narratives about human capital and productivity.

However, institutional comfort with existing methodologies can drift into institutional complacency. The Fed’s researchers are solving the problems they know how to solve, using the tools they’ve always used, rather than asking whether those tools still fit the situation.

The real challenge: When economic models become too detached from economic reality, they stop serving the people they’re meant to help.

Families don’t live in spreadsheets. They live with tuition bills, student loan payments, and career uncertainty that the Fed’s models barely acknowledge.

Beyond the Numbers: What Families Face

The Fed’s analysis exists in a vacuum, divorced from the lived experience of American families. Here’s what they miss:

Financial stress: With 43 million Americans carrying $1.78 trillion in student debt, families are making desperate calculations about mortgage payments, retirement savings, and basic financial security.

Regional variation: The Fed’s national averages obscure massive regional differences in college costs and post-graduation earning potential.

Career uncertainty: In an economy where entire industries can be disrupted overnight, the Fed’s assumption of steady, predictable career earnings is increasingly naive.

Mental health impacts: The psychological toll of financial stress, career uncertainty, and debt burden doesn’t appear in ROI calculations but shapes millions of lives.

What We Need From College ROI Models

We’re not asking for perfection.

We ask for intellectual honesty and methodological rigor that serve families rather than institutions.

Essential improvements:

- Use current, accurate cost data that reflects what families pay

- Adjust for take-home pay, not just gross earnings

- Model realistic graduation timelines as the norm, not the exception

- Account for regional and institutional variation in both costs and outcomes

- Include non-completion risk in baseline calculations

- Acknowledge career uncertainty in long-term projections

- Adjust for the time value of money, no investment that incurs costs up front but receives benefits over an extended period should be completed without a time value analysis.

The bigger picture: ROI models should help families make informed decisions, not provide false reassurance that preserves institutional comfort.

The Path Forward: Honest Analysis for Hard Choices

College can be worth it for some students, in some programs, and under certain circumstances. But the days of treating higher education as a universally safe investment are over.

What families need:

- Transparent, realistic cost projections

- Major-specific outcome data

- Regional employment market analysis

- Alternative pathway comparisons

- Risk-adjusted return calculations

What policymakers need:

- Honest assessments of higher education’s limitations

- Analysis of vocational and alternative career paths

- Recognition that college isn’t the only path to middle-class prosperity

What researchers need:

- Methodological humility

- Willingness to challenge institutional assumptions

- Connection to real-world family experiences

Final Thought: When Precision Becomes Deception

The Fed’s 12.5% ROI claim sounds precise, authoritative, and reassuring. But precision isn’t the same as accuracy.

When models rely on outdated costs, idealized timelines, and institutional biases, they become less a mirror of economic reality and more a projection of institutional comfort.

Families deserve better.

They deserve research that acknowledges the actual costs, realistic timelines, and uncertain outcomes that define modern higher education.

They deserve models that help them navigate difficult choices rather than models that make institutions feel better about their recommendations.

The college affordability crisis isn’t solved by pretending it doesn’t exist.

It’s solved by honest analysis, realistic expectations, and policy responses that address the gap between institutional promises and family realities.

If we want to restore trust in higher education and the research that supports it, we need to start with humility, better questions, and the courage to admit when our models no longer serve the people they’re meant to help.

College is still worth it for some. We need to stop pretending it’s a safe bet for everyone because the data, when honestly analyzed, tells a very different story. Until we confront the root causes, we will continue to disappoint many American families investing in college degrees.

Reference Sources

- https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w33684/w33684.pdf

- https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/04/is-college-still-worth-it/

- https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/04/when-college-might-not-be-worth-it/

- https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_330.10.asp

- https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/Trends-in-College-Pricing-and-Student-Aid-2024-ADA.pdf

- https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/Trends-in-College-Pricing-and-Student-Aid-2024-ADA.pdf

- https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/loo-young-adults-in-the-parental-home-2007-2023-fp-24-02.html

- https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=569