When I went to college, there was rarely any doubt that a college investment made sense. Tuition and fees were much lower, and demand for graduates was high while supply was low. The result was a significant wage increase after college, more than enough to cover costs.

Since then, we have seen an explosion in the number of college offerings, fees have increased dramatically, and the supply of graduates has increased while demand growth slowed. Wages didn’t grow at the same rate that costs increased.

At present, the value of a college degree is a subject of intense scrutiny for high school graduates. The uncertainty they face is palpable, and there is a growing emphasis on understanding the return on investment of a college degree.

A simple Google search for ‘college return on investment’ yields 304 million results. This popularity indicates the growing attention and concern around this topic, a call for educators to adapt to the changing landscape.

In this article I will share with you the method I believe best captures the essence of the costs and benefits. If you agree with me, this method will help you objectively answer when college is a good investment, or help you decide which is the best choice for you.

Read on for the details.

“The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.”

Dr. Seuss

What do we mean by College Return on Investment?

A college return on investment (ROI) measures the financial value of a college degree to someone. Typically we talk about the return from the family/student perspective. However, we can apply the same methodology for measuring the return to donors, the government or even the college itself. We explore this ecosystem more full in the next piece: College return on investment? Whose ROI?

For now, lets stick with exploring how one goes about calculating the college ROI.

Attending college incurs costs you hope to recover through higher earnings after graduation. Indeed, college wont be a good investment unless you recover much more than the costs you incur.

These costs will occur upfront while attending college, while the increased earnings will happen after graduation and, hopefully, persist through retirement.

So, we need a method to effectively compare all the costs of attending college (tuition, fees, living expenses, etc.) to the increased lifetime earnings associated with having that degree.

Return on Investment Model

The typical high school graduate has several choices—whether to attend college, which college, which field of study, etc.). They may also have some financial constraints limiting what they can afford or how quickly they graduate.

Our investment model must be robust enough to help with decision-making.

Investors faced with multiple investment choices with similar complexities use the discount cash flow model to calculate the net present value of their various options. The better choice has the highest net present value.

Can we apply this model to a college investment?

Absolutely.

It is the most accurate method for adequately evaluating the various outflows and inflows and comparing choices.

The Base Case – No college

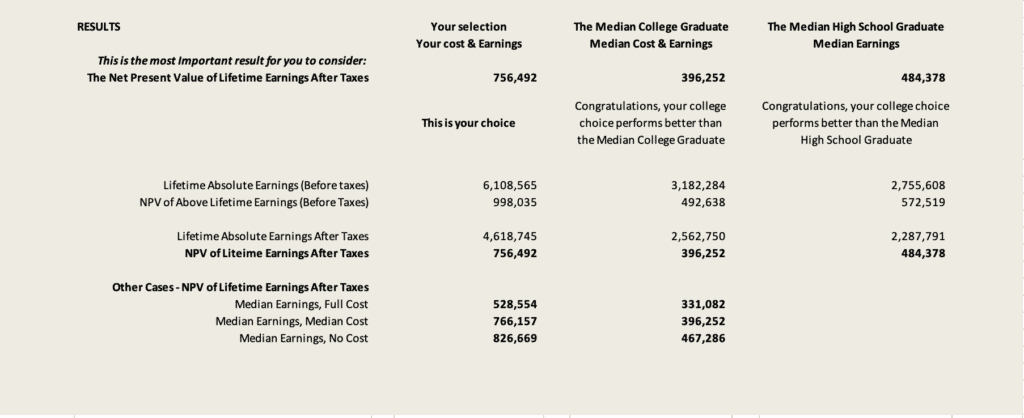

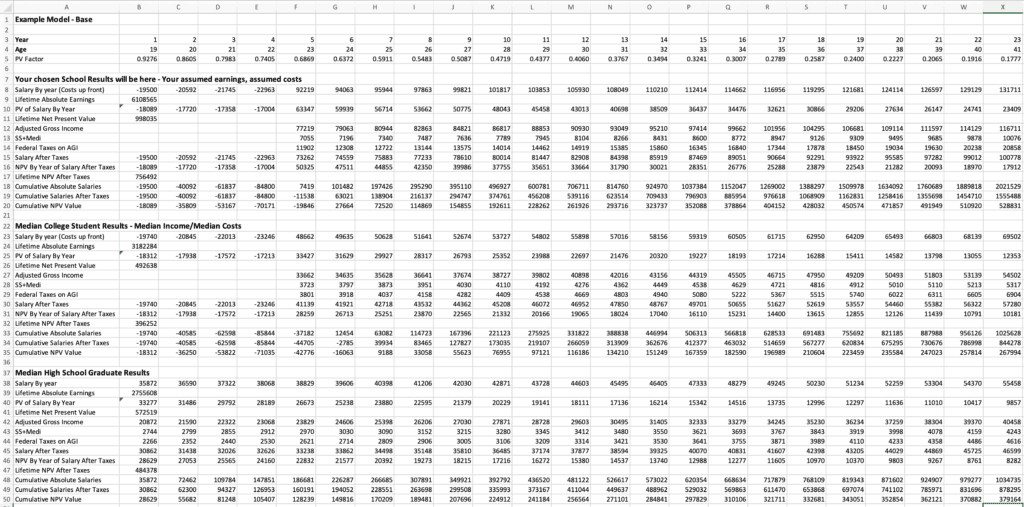

The first choice we should consider is the base case or benchmark. The base case is what happens to high school graduates if they do not attend college. We want to compare your college choice against this benchmark.

The high school graduate goes to work, and we calculate how much they earn over their lifetime.

For us to properly build the base case, we need to understand what the typical high school graduate earns and project what they will earn each year until retirement.

To keep things simple, our model assumes the high schooler graduates at 18 and continues to work until they are 65.

We use the national median salaries for high school graduates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

We increase the earnings each year by 2%, which is the long-term annual wage increase rate.

Note on High School Salaries: You can adjust the starting salary and growth rates based on your situation, skills, and expectations. We caution against the universal bias to consider ourselves above average and suggest you use the median as the baseline and calculate additional scenarios with your specific adjustments.

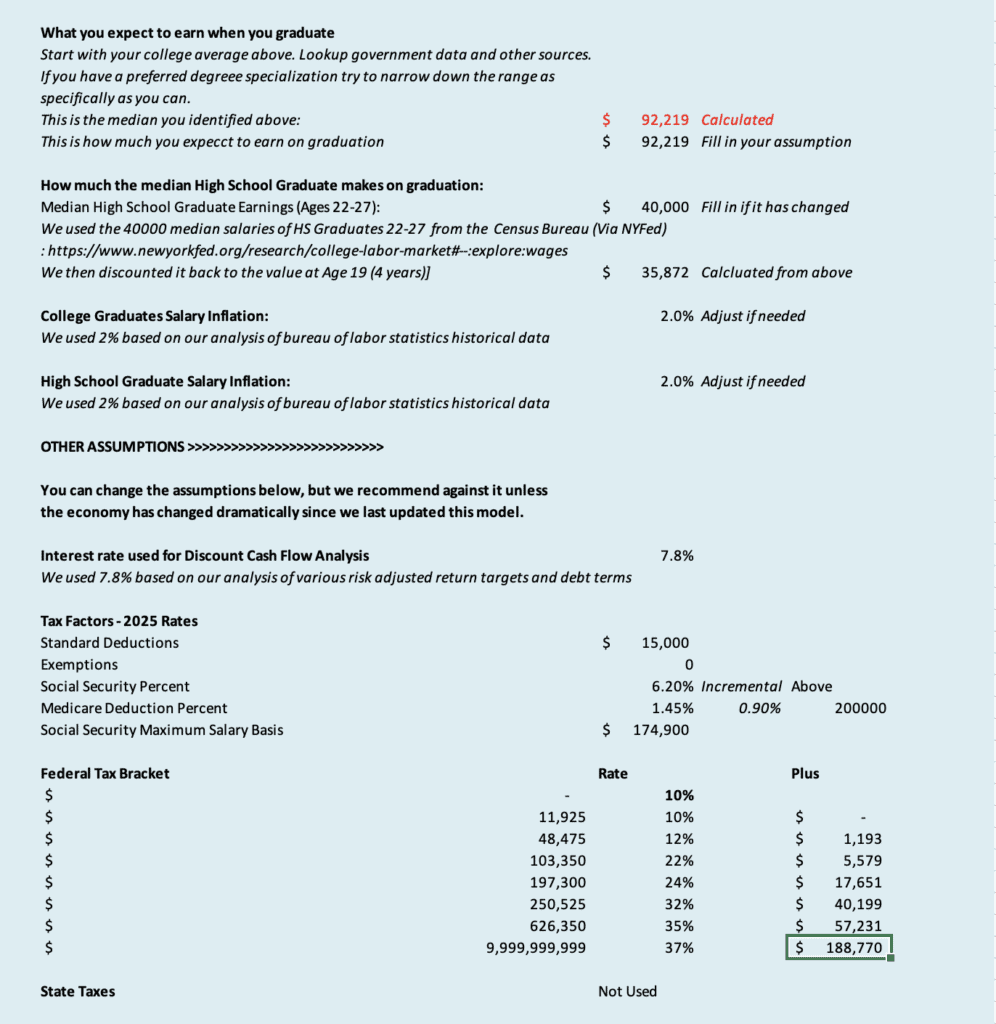

We calculate the taxes on those earnings using the current tax rate tables for a single person each year.

If you go to work after high school, you do not incur any incremental costs such as those for a college degree. So, we dont have to deduct anything additional from the earnings stream.

Finally, we take the earnings after subtracting taxes each year and calculate their worth on high school graduation date.

The total of all the earnings over your lifetime represents the net present value of your after-tax earnings as a high school graduate (HS-NPV-AT). You will measure your other options against this baseline.

Your college degree would be financially worthwhile if its net present value exceeds this benchmark.

Evaluating your College Choice

We need to build a similar model of all your costs and earnings related to your college choice.

Our model assumes the typical student goes to college full-time and graduates in four years.

In those years, you will incur expenses related to attending college. These include tuition, fees, living expenses, books, and other related costs.

You will reduce these costs by any scholarships or grants you receive from your chosen college. The remainder is your net costs to attend college.

Please note that we do not reduce the costs by any loans, only cost reductions you do not have to repay. You must repay any student loans you take to pay for college so they don’t reduce your costs. They only change when you pay those costs yourself.

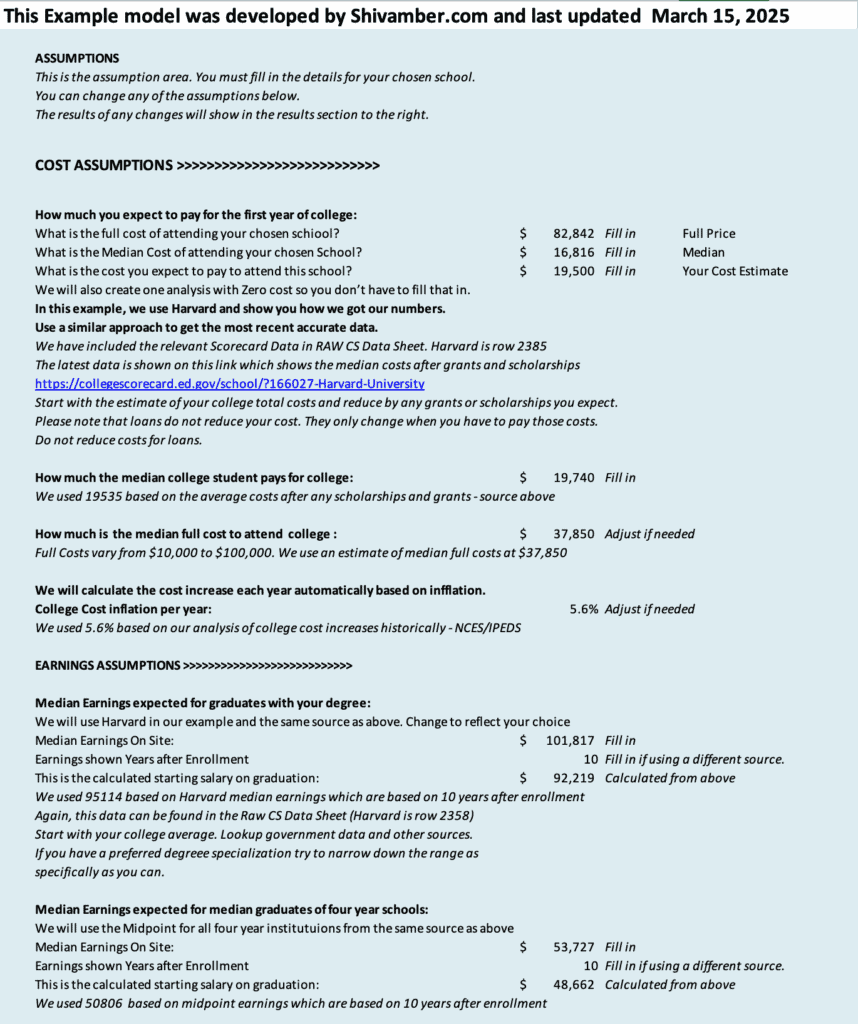

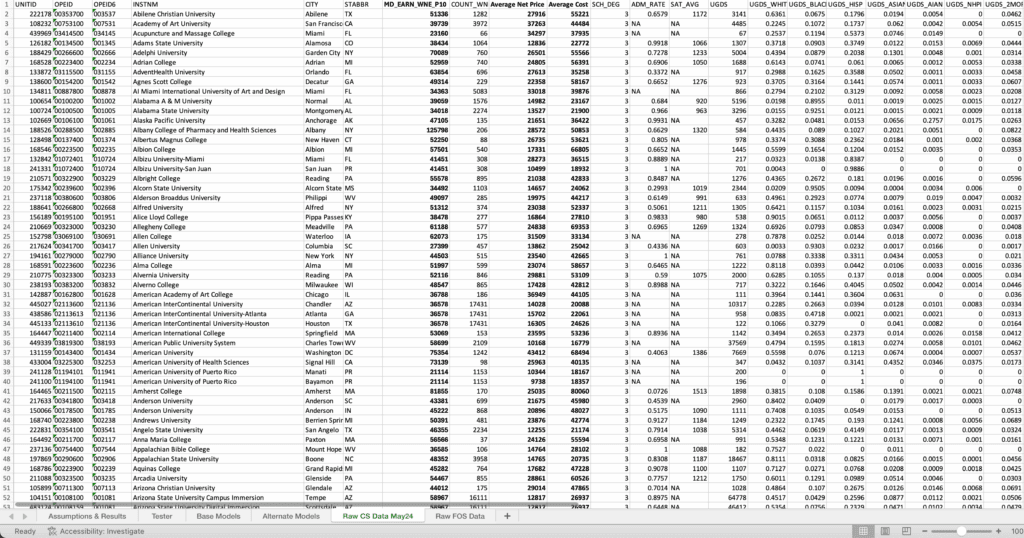

Note on College Costs: Our model starts with the College Scorecard median costs by college. However, we caution that their data is based primarily on students receiving aid. Use the college calculators wherever possible to estimate your estimated expenses. Assume you will receive assistance if you are an exceptionally talented student or a member of a financially constrained family. We suggest you also use the total price of your chosen institution as another comparison point.

To keep things simple, our model assumes you graduate college and continue to work until you are 65.

Note on College Salaries: The College Scorecard provides median salaries by college. However, the data they provide is “The median earnings of former students who received federal financial aid at 10 years after entering the school.” This number is likely inflated versus starting salaries after you graduate college. In our model, we give the benefit of the doubt to the college graduate. We use that salary and deflate it by about six years to determine your starting salary graduation.

Further, since salaries vary dramatically based on your chosen field of study, use its given median salary if available. You can find the field of study median salaries for your college in various databases online.

Once we identify your starting salary after graduation, we increase the earnings each year by 2%, which is the long-term annual wage increase rate.

You can adjust the starting salary after college and growth rates based on your situation, skills, and expectations. We caution against the universal bias to consider ourselves above average and suggest you use the median as the baseline and calculate additional scenarios with your specific adjustments.

We calculate the taxes on those earnings using the current tax rate tables for a single person each year.

Finally, after subtracting taxes each year, we take the expenses and earnings and calculate their worth on high school graduation date. That is the date when you are making the decision to pursue the alternate path, rather than the base case.

The total of all the earnings over your lifetime represents the net present value of your earnings after-tax and costs as a college graduate (CG-NPV-AT). You will measure these options against this baseline.

Your college degree would be financially worthwhile if its net present value exceeds the HS-NPV-AT benchmark.

Reference Sources

- U.S. Department of Education College Scorecard. ”College Scorecard.” Collegescorecard.Gov. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://collegescorecard.ed.gov.

- U.S. Department of Education College Scorecard. ”College Scorecard.” Collegescorecard.Gov. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/data.

- Ma, Jennifer, and Matea Pender (2022), “Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2022, New York: College Board. © 2022 College Board. https://research.collegeboard.org/trends.

- U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics. ”Digest of Education Table 326.10 Graduation Rate.” Nces.Ed.Gov. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_326.10.asp?current=yes.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. ”The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates – Distribution of Annual Wages.” Newyorkfed.Org. February 22, 2024. https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market#–:explore:wages.

- Daly, Mary C. “Is It Still Worth Going To College?” Research & Insights Economic Letter, no. 2014-13. Accessed July 14, 2024. https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/2014/05/is-college-worth-it-education-tuition-wages/.