In the USA, nearly six thousand institutions offer higher education programs to students.

Many receive private support for their mission through donations from social impact investors, alumni, and foundations.

All of them receive some federal or state funding to support attendance partially.

Financially qualified students attending any of these institutions are eligible for Federal Pell Grants. They are generally at the lower end of income earners and asset owners.

The Pell Grant is a laudable attempt by the Federal Government to provide college cost relief to the financially challenged.

Here’s why and how those federal investments can do much better.

“An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

Benjamin Franklin

What is the purpose of the Pell Grant?

The purpose of the Federal Pell Grant is to provide financial assistance to low-income undergraduate students to promote access to postsecondary education. (1)

Critical aspects of the Pell Grant’s purpose include:

- Helping students with exceptional financial needs pay for college expenses, including tuition, fees, room and board, and other educational costs.

- They are increasing college affordability and accessibility for students from low-income backgrounds.

- Unlike loans, it provides need-based grants that do not typically require repayment.

- It supports undergraduate students who have not yet earned a bachelor’s degree and certain post-baccalaureate students enrolled in teacher certification programs.

- It is a cornerstone of federal student aid, established by the Higher Education Act of 1965 to help make higher education more attainable for those with limited financial resources. (2)

The Pell Grant aims to bridge the gap between a student’s expected family contribution and the cost of attendance at their chosen institution.

By offering this financial support, the program seeks to reduce barriers to higher education and provide opportunities for students who might otherwise struggle to afford college.

While Pell Grants aim to do a social good, policymakers and the taxpayers who fund them usually want to see their money put to good use and have a positive social impact.

The premise for supporting college attendance is that it leads to higher incomes and benefits the economy. One would expect to see higher taxes generated by these higher-paid college graduates.

Are those assumptions based on fact?

Do all college degrees return higher incomes and higher taxes?

How can policymakers evaluate the Pell Grant as an investment?

Do Pell Grants generate a high social benefit at every degree and institution?

A Model for Evaluating Pell Grants

We have developed a comprehensive model that quantifies the potential social impact of college investments and provides a consistent and normalized approach for evaluation.

On the government side, we assume the maximum Pell Grant of $7,395 for each of four years for a student. The total cost to the government is $29,580.

The total grant funds are a part of a student’s four years of full-time attendance (assuming that is the time for graduation).

We can estimate the value of each student’s education at their respective institution by calculating the Net Present Value of their Lifetime Federal Taxes generated (NPVLFT).

We can calculate the NPVLFT for the median college student nationwide and a benchmark or base model for the median high school graduate who does not attend college.

The student could have graduated from high school and gone to work, so the marginal impact is the incremental difference between the value created by a high school graduate and the Pell Grant.

In other words, it represents the additional value that the Pell Grant brings to the student and society compared to the scenario in which the student does not attend college.

The Pell Grant returns are the Incremental Net Present Value of Taxes created, divided by the total Pell Grant investment.

The Harvard Example:

The Department of Education provides data on Pell Grants awarded by Institutions, and the latest data shows that 1,251 Harvard students received $5,602,695 that year. (3)

The Harvard average total four-year costs are $353k, and an NPV of $292k. While the average Pell grant is about $4.5k, we will assume the maximum grant for simplicity, so the $29,580 funds 10% of a student’s cost.

The Net Present Value of the Lifetime Taxes for a median Harvard Graduate is $352k per student.

A median high school graduate who does not attend college creates an NPV of $111k in taxes.

Enabling this student to attend Harvard instead of going straight to work creates an incremental net present value of $241k in taxes per student ($352k-$111k).

Remember that Pell only funded 10% of the Harvard Education. So, the total marginal value created for that funding is $24.1k each (10% of the $241k). This investment return is well below the original Pell Grant ($29,580), which was invested in that student and generates a negative return of 18%.

Harvard is a great institution; its graduates are well-rewarded in the marketplace and receive very high salaries.

They generate a significantly higher average tax benefit to the nation. However, Harvard is costly, and the Pell Grant only funds a small portion of a student’s attendance.

Thus, investing in Pell Grants at Harvard is a losing proposition for taxpayers.

Indeed, Harvard can provide funding to all its students without Pell Grants.

The University of Phoenix Example

The University of Phoenix offers an instructive case study—one that reveals both the complexity of evaluating educational investments and the depth of systemic failure in higher education returns.

Consider the conventional narrative: Phoenix, a for-profit institution, received $197 million in Pell Grants for 51,990 students in 2017-18, making it the third-largest Pell recipient nationally. Maximum Pell Grants cover 43% of four-year costs. Yet median graduate salaries of $37,769 generate lower lifetime tax revenues than high school graduates produce. The Pell return? A devastating -123%.

This appears to validate the reflexive dismissal of for-profit institutions as predatory degree mills. But this interpretation misses critical nuances, and in doing so, obscures a far more troubling reality about American higher education.

The Damning Comparative Context

Perhaps most revealing is Phoenix’s performance relative to the broader institutional landscape. Analysis of the 5,400+ institutions reporting to NCES demonstrates that the University of Phoenix outperforms approximately 2,200 institutions, over 40% of all colleges and universities, in graduating students who earn above high school graduate benchmarks.

Pause to consider that implication: A for-profit institution widely criticized as exploitative produces better earnings outcomes than nearly half of America’s colleges and universities, many of them traditional nonprofits enjoying reputational advantages and public subsidies.

If Phoenix, with its flexibility and eliminated opportunity costs, struggles to generate positive Pell Grant returns, what does this reveal about the vast number of institutions it outperforms? The data suggests a systemic failure far broader than the for-profit sector.

The Inescapable Conclusion

This creates a disturbing calculus: Many Pell Grant recipients attending the University of Phoenix would generate higher lifetime earnings and greater tax revenues by entering the workforce directly after high school. Taxpayers would avoid the grant expenditure entirely while collecting more tax revenue over the graduate’s lifetime.

Yet Phoenix represents a superior investment compared to thousands of traditional institutions. These colleges combine Phoenix’s low graduating salary outcomes with the traditional model’s crushing opportunity costs—and often charge premium prices while doing so.

The University of Phoenix case illuminates an uncomfortable truth: When an institution purpose-built to serve working adults, operating at scale with substantial cost efficiencies, delivering genuine flexibility unavailable elsewhere, and outperforming 40% of all colleges still cannot generate positive returns on federal investment, we face a systemic crisis in how America deploys educational capital.

The question is no longer whether specific institution types succeed or fail. It is whether the entire framework through which we evaluate, fund, and credential higher education remains fit for purpose.

What about Top Schools?

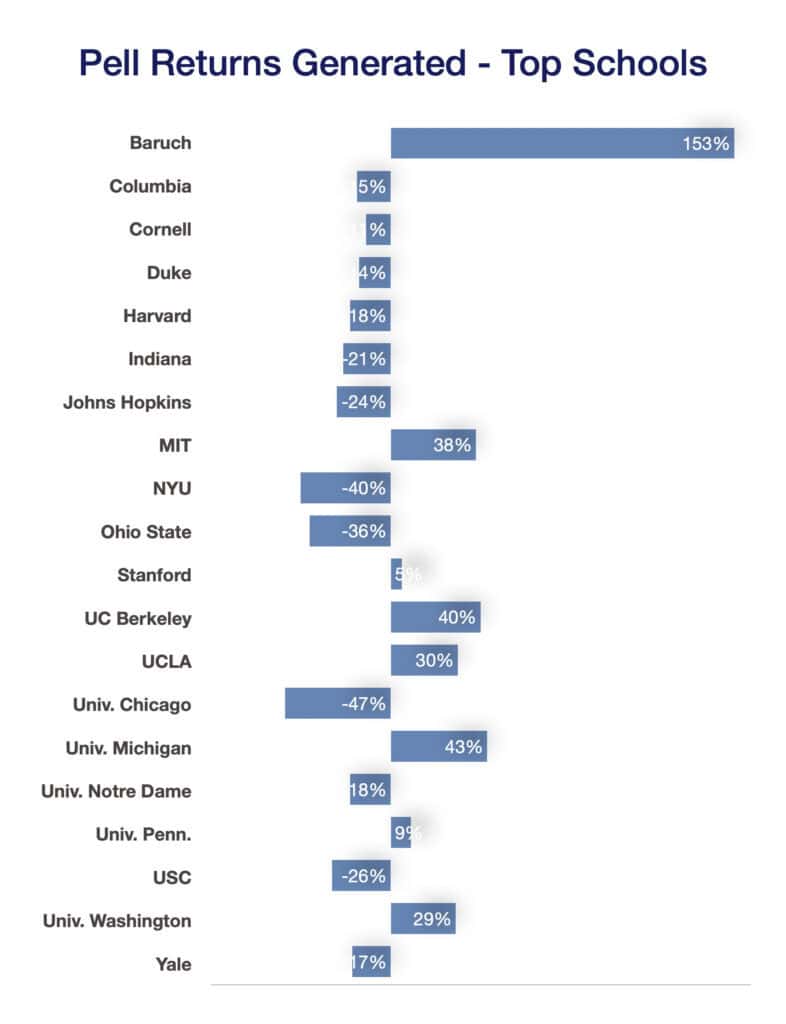

The marginal returns from Pell Grants in the top schools are generally bad propositions, though better than those of the median college graduate at a disastrous -66%!

We have determined that the median college graduate (earning below the median salary and paying above the median costs) generates subpar returns to the median high school graduate.

You may have noticed that several schools generate a positive return for Pell Grants. Why is that?

When the Pell Grant funds a degree that generates exceptional salaries at lower costs, the return on the Grant can be positive.

This disconnect demonstrates the challenge of famous institutions. These institutions generate high value for the individual student. However, their costs are so high that fewer can attend and are fundable with a specific donation or grant.

Could other schools better balance costs while generating high student values, allowing comparably high donor investment returns?

A high-return hidden investment gem

For the Pell Grant Returns to be high, the student must attend a college that is more affordable than those profiled and produce students whose value is also dramatically higher than that of the high school graduate.

One such institution that stands out is Baruch College, a part of the City University of New York System. Full disclosure: Baruch is my alma mater, and I am on the Board of the College Fund.

With its low attendance fees and high median student returns, it presents a unique opportunity for high returns on donor investments.

Due to its relatively low cost and high returns to graduates, Baruch excels.

The Maximum Pell Grant pays for 50% of a student’s tuition, and the marginal return is a whopping 110% over the original investment.

Yes, you read that right. The social impact return of donors’ investments in Baruch is almost eight times that of MIT, blowing away the results of the other schools profiled.

In our earlier chapter reviewing donor returns, we showed the many other comparisons that establish why Baruch College is a gem. It would be worth your while to review those again.

Implications for Policymakers

Pell Grants aim to help low-income high school graduates attend college.

However, depending on the chosen field of study and college, the student return could vary dramatically.

The Pell Grants are better used to fund students in reasonably priced institutions that generate good salary outcomes for their students.

Reference Sources

- U.S. Department of Education Federal Student Aid. ”Federal Pell Grants.” Studentaid.Gov. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://studentaid.gov/understand-aid/types/grants/pell.

- Pell Grant. (2024, May 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pell_Grant

- U.S. Department of Education. ”Distribution of Federal Pell Grant Program Funds by Institution.” Www2.Ed.Gov. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://www2.ed.gov/finaid/prof/resources/data/pell-institution.html.