The market assumed Apple was in trouble with Tariffs. At one point last week, it traded as low as $172 per share, a 34% drop from its peak. That price drop is building in massive pessimism around the business. Here is why that doomsday view is overdone.

“I’m not smart, but I like to observe. Millions saw the apple fall, but Newton was the one who asked why.”

William Hazlitt

First, the tariff approach was unlikely to hold (as of this writing, it appears to have been temporarily exempted). That’s a good thing. I will explain why below.

Second, people who assume Apple is doomed will likely discount many options available to Apple and any producers assembling products in China. This will be explained below.

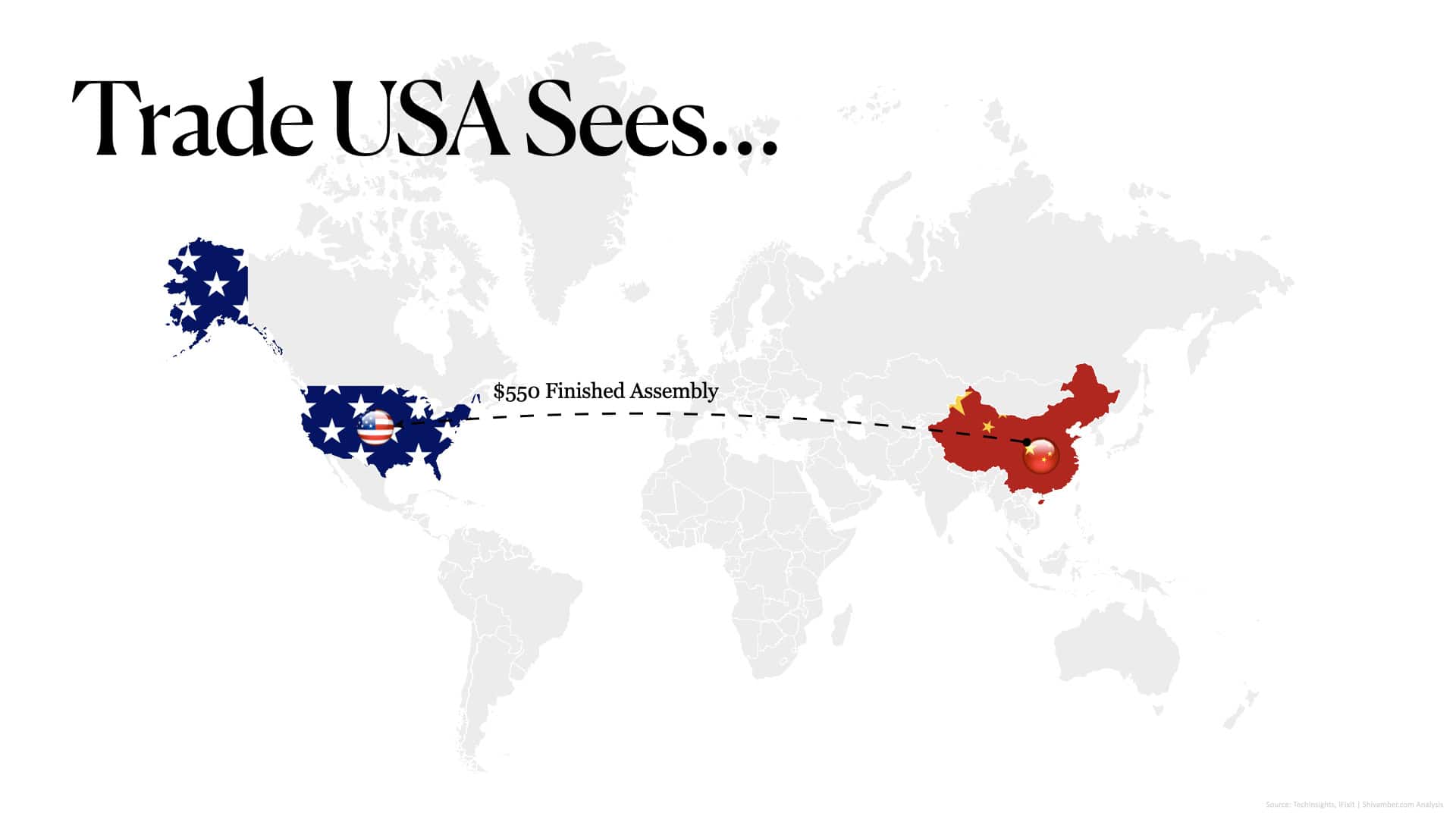

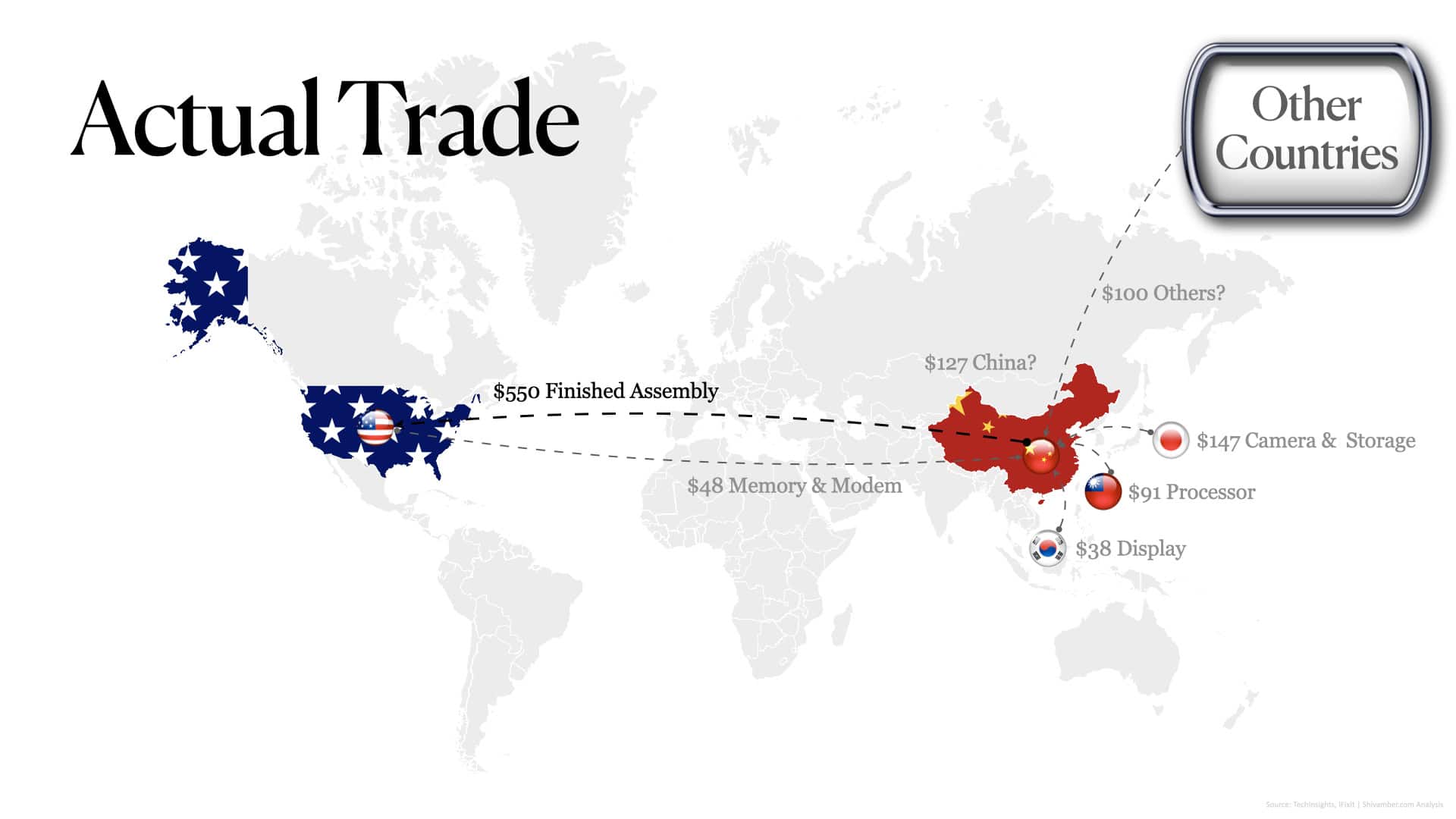

In exploring the above, it will become evident that those who declare this is only about China and want to limit the scope need to better understand the hidden flow of trade. I won’t spend much time explaining that issue here; I will tackle it comprehensively in another piece. I will leave you with a simple teaser: If we look at the hidden trade, not just the visible trade, China will likely continue to be a challenge, but other nations will also emerge as significant challenges.

But back to the Apple tariff problem. Some of what I cover will seem obvious, but it is helpful to understand if you want to figure out the underlying issues and challenges with the trade imbalance. Here is the scenario envisioned before the tariff exemption this weekend:

You’re about to snag the latest iPhone, but the price tag has ballooned by $800. The culprit? 145% Tariffs. You’d think those extra costs are sticking to China, but in reality, they end up hitting a lot of others, including the American consumer, and the innovation that powers our favorite American gadgets. It’s time to reconsider the tariffs on Apple products from China. Here’s why and how we can do it smarter.

Apple Tariffs Deserve a Second Look

The heart of the issue is simple: tariffs on iPhones don’t work as they should. A disproportionate value of the iPhone comprises components sourced outside China, yet the tariffs punish those suppliers, American consumers, and innovation more than anyone else. There are even proven supply chain mechanisms that could soften the blow without breaking any rules. Let’s break it down.

The iPhone’s Global Roots Run Deep

The iPhone isn’t “made in China” in the traditional sense, it’s assembled there. In reality, it’s a global masterpiece. Think of it as a world tour: the processor hails from Taiwan, the display from South Korea, the rear camera array from Japan, and the 5G modem from the U.S. A Wall Street Journal article: “An American-Made iPhone: Just Expensive or Completely Impossible?” suggests the iPhone 16 Pro’s bill of materials (BOM) is approximately $549.73. Here’s the lineup:

| Component | Source Country | Cost Estimate |

| Rear Camera Array | Japan | $126.95 |

| Processor | Taiwan | $90.85 |

| Display | South Korea | $37.97 |

| 5G Modem | USA | $26.62 |

| Memory | USA | $21.80 |

| Main Enclosure | China | $20.79 |

| Storage | Japan | $20.59 |

| Battery | China | $4.10 |

| Other Components | other countries, including China | $200.06 |

Over 50% of the value of components comes from outside China. Labor and overhead added in China are estimated at less than 10% of the total cost, under $54.97. Yet, when tariffs hit the finished iPhone, they tax the whole $549.73, consisting of all those non-Chinese parts and American design.

Tariffs Hurt Americans More Than China

These tariffs are a boomerang, they come right back to hit U.S. consumers and the economy.

The content from China affected is estimated to be less than a third of the value. The complete content tariff scheme jeopardizes the other $424 contributed from different countries. Additionally, It jeopardizes the $500 markup Apple gets in the USA when it sells that phone.

Imagine a $800 tariff bump per iPhone. With Apple selling over 60 million units yearly in the USA, that’s $50 billion in extra costs to consumers. Apple might partially absorb it, hitting its profitability and shareholders. But much of it will come from the consumer wallet. That’s $50 billion less for Americans, including any portion Apple chooses to absorb, to spend elsewhere, potentially stalling economic growth.

Then there’s the job factor. Apple employs over 80,000 people directly in the U.S. and supports hundreds of thousands more through its app ecosystem and supply chain. Tariffs that squeeze Apple could mean less investment in innovation or even layoffs. It’s not merely reduced profitability and a higher price tag, it’s a ripple effect that could dampen innovation in the tech sector and beyond.

The Applicable Tariff Should Be Lower

A tariff on the entire content doesn’t exclusively hurt trade between the USA and China; it hurts trade between the USA and many other good trading partners. Consider the $126.95 camera accessory from Japan. It is counted as trade between Japan and China, but in reality, it’s trade between Japan and the USA, with a detour in China. We should look for ways to promote trade with partners, not reduce it.

When considering the content contributed by China, we estimate about one-quarter of the bill of materials. If we apply 145% tariffs on Chinese content (estimated $127), the bill added is $184, not $800. That equates to about 33% tariffs on the total bill of materials. If the administration wishes to penalize Chinese content, then that is the amount we should focus on. It’s a sizable penalty that will keep Apple focused on alternatives.

The administration’s solution requires Apple to reroute production of US demand outside China. There is talk of Apple supplying products from India. However, that solution requires time to reach the scale needed to meet the demand in the USA. It may never be able to supply the entire mix of products coming from China. Thus, Apple expects to live in a tariff world until the China-U.S. trade dispute is resolved.

In that tariff world, the most straightforward and ideal approach to implementation is to adjust tariffs based on Chinese content rather than apply them indiscriminately to the total BOM.

Suppose the administration does not want to tailor its approach to individual suppliers’ Chinese content. In that case, it should allow companies like Apple to adopt legitimate supply chain practices that can produce the same effect.

There are other ways to get the same effect.

Smart Historical Alternatives Exist

Alternative supply chain practices can be adopted to ease this tariff pain, which has been done before.

In the electronics industry, companies have used clever supply chain approaches to protect intellectual property (IP), including critically important competitive advantage information such as cost.

When I ran the electronic component supply chain for Arrow Electronics, we had systems that allowed suppliers of important technology components to tailor their supply price to end customers. Big OEMs like Cisco would receive a unique price for their components compared to other buyers of the same component from the same supplier. Prices were legally tailored to reflect the cost to serve customers, their importance, the volume of purchases, and the technical support required, among other factors.

Good Reasons To Mask Prices

When the outsourcing movement began shifting dramatically from owned factories to outsourced electronic manufacturers, there was a concern about protecting import IP, such as component pricing.

Big electronic buyers worried that their price could be revealed to the competitors who could use that information to derive price concessions from component suppliers, diluting advantage. Worse, we began to see unscrupulous assembler pool demand for components receiving supply at the lowest cost and offering discounts to OEMs faced with higher supplier component prices. Some assemblers bought extra components at the lowest prices of their customers and supplied those to other customers at higher prices, pocketing the difference.

This loss of IP and potential pricing collapse became an existential crisis for component producers and their OEM customers. Companies like Cisco at the time desperately wanted to hide key component pricing from assemblers. This aligned with the interests and capabilities of distributors like Arrow, which provided engineering support to OEM designers. With no method to track component supply or extract a margin to fund engineering support, companies with design houses in North America and assemblers in Asia or other regions stood to lose all technical support. Worse, pricing could slide to the lowest experienced by the biggest customer of an assembler. Suppliers stood to lose higher margins received from lower volume OEMs.

Several methods were devised to address many of those concerns.

Kitting Services

The first iteration of supply chain solutions included various value-added services dubbed “kitting” services. I had a business in my portfolio of services that collected a kit of all the essential controlled components needed to supply the assembler. These were shipped and tracked separately from everything the assembler required and provided.

We sometimes provided the entire Bill of Materials and charged the OEM (like Apple) for those costs. The assembler provided their services in a separate bill to the OEM.

This approach added complexity but worked spectacularly for startups not interested in building their manufacturing capabilities. More importantly, it protected IP. The fastest-growing industry at the time, networking and communications, embraced this solution.

Unfortunately, for clients with high-volume requirements or low-margin production, partial kits did not scale. An additional dollar expense on millions of units quickly adds to a lot of money. For those cases, we needed a new solution.

Price Masking

Kitting requires suppliers to ship to a consolidation point, such as my value-added operation. The components are then shipped in a kit to the assembler, and the remaining components, after production, are returned to our value-added operation. Those extra steps added up, and with our new solution, we eliminated them.

Instead, suppliers ship components to assemblers, like Foxconn in China,at an artificial price or zero value. The pricing was of no competitive value, even if it leaked to other competitors (who might be using the same assembler). In this case, the IP owner (Cisco or Apple) pays suppliers directly for the component cost, adding it back to the BOM later. The assembler accounts for their bit, labor and local parts supplied. On receiving the final product, the OEM stitched together the prices for a complete accounting of the product value.

It is more complex accounting and shifts the timing of component cash flow, but the supply chain works the same way as if the assembler is buying everything.

The Assemblers did not like this approach. They lost purchasing leverage and competitive information. More importantly, assembler pricing models had always added a handling fee, calculated as a small percent of component value, and that was shrinking.

It worked until the people who ran manufacturing and supply chains no longer cared about protecting IP. They shifted all responsibilities to the assembler, except for negotiating significant component pricing with suppliers. They gave up tracking supply so that purchases at their prices were not diverted to other customers. Then, these solutions were no longer prevalent.

Perfectly Legal and Tariff Adjusting

These methods are not about dodging taxes but safeguarding proprietary information. Components used in products exported from China are imported duty-free into China because they’re destined to leave in a finished product. The assembler’s profits and value-add stay untouched, but the declared value of the assembled iPhone drops. That means tariffs apply to a smaller number, not the complete BOM stuffed with non-Chinese value.

These methods were not devised to cheat authorities, they are legitimate business plays to protect IP. But they can double as a tariff shield. With tweaks, Apple could lower its tariff exposure, keeping costs down for consumers without breaking trade rules.

Why This Matters Now

In a world where innovation zigzags across borders, tariffs on the entire iPhone feel like a relic. They miss the global reality of modern supply chains and hit American wallets hardest. But by rethinking these tariffs and tapping into proven strategies, we can protect consumers, fuel innovation, and craft a sensible trade policy.

Time to Think Different

Tariffs on the full value of Apple products are a blunt tool in a precision-engineered world. They tax a global network of creativity while leaving Americans to foot the bill. Let’s reconsider them, using a more rational tariff rate depending on content sourcing or with strategies like IP protection, not to skirt the law but to align trade with reality. In the spirit of Apple’s mantra, it’s time to think differently about tariffs and keep innovation thriving.

Apple and other Electronic OEMs have options:

- Get a reprieve on tariffs

- Move the supply of US demand out of China,

- Convince the administration to reconsider Tariff rates based on content source,

- Consider kitting foreign components to assemblers,

- Consider price masking of foreign components.