The Federal Reserve regularly reports on the state of wealth in America. One issue they frequently discuss is the wealth premium, like the wage premium, of college graduates.

The implication is that income and wealth are heavily influenced and indicative of the value of college.

In this essay, we examine the claim. Does the state of America’s wealth, and specifically the college wealth premium, say much one way or the other about college value?

Read on to find out.

“Wealth is the product of man’s capacity to think..”

Ayn Rand

Federal Reserve Researchers and countless other academic scholars have been documenting and exploring the College Wage Premium for decades. In the 1980s, faced with criticism that the wage premium measure ignored College Costs, the St. Louis Federal Reserve introduced the College Wealth Premium.

Most of the wealthy have retirement accounts and trusts. Knowing that does not mean we should go out and subsidize everyone’s signing up for a retirement account or trust. We know that merely having one of those will not necessarily raise the wealth of those who need one.

We instinctively understand there is a wide ocean between correlation and causation. Things that are frequently seen together and highly correlated don’t necessarily explain or cause the thing we observe.

Consider the following:

- Historically, the wealthy got college degrees because they could afford to.

- The exceptional student could get a college degree because they were exceptional. Armed with a college degree, they could amass wealth.

- People with college degrees were wealthier.

Should we assume that college degrees caused the wealth?

Knowing the above does not mean that subsidizing college degrees will generate wealth for those who are not wealthy or exceptional.

The wealthy could have generated more wealth without college degrees. The exceptional can derive wealth without degrees.

The premise that people with college degrees have more wealth does not prove that the current college degree choices will drive wealth. Because the wealthy drive expensive cars, it does not mean donors and the government should subsidize the purchase of expensive vehicles for those not wealthy. The same is true for college.

In the investment world, there is an omnipresent warning: “Past performance is no guarantee of future returns!”

We probably should have titled this essay “Researchers found that people who get more gifts have more gifts than people who don’t get gifts.” But we are getting ahead of our story.

Early College Wealth Research

In a 50-page report published in 2020 titled The College Wealth Divide: Education and Inequality in America, 1956-2016, the authors, in their introduction, pay homage to the problematic wage premium:

“It is a well-documented fact that the college wage premium has increased substantially since the 1980s (see, e.g., Levy and Murnane,1992; Katz and Autor, 1999; and Goldin and Katz 2007).”

Acknowledge the rational reality of supply and demand:

“This trend can be traced back to differences in the growth of the demand for and the supply of college-educated workers that are driven by skill-biased technical change, socio-demographic factors, and institutional features (Card and Lemieux, 2001, and Fortin, 2006).”

And lean in to the college wealth premium hypothesis:

“Recent work has begun to analyze the relationship between college education and wealth inequality (Emmons, Kent, and Ricketts, 2018, and Pfeffer, 2018) and demonstrates an increasing association between college education and wealth.”

Those are the first three sentences of the introduction.

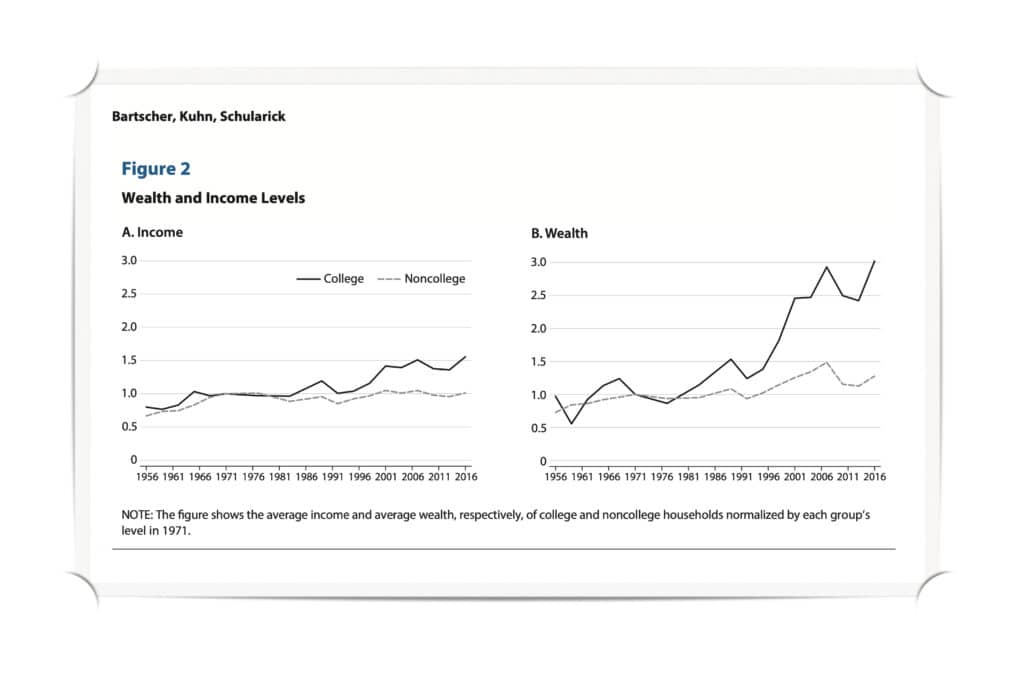

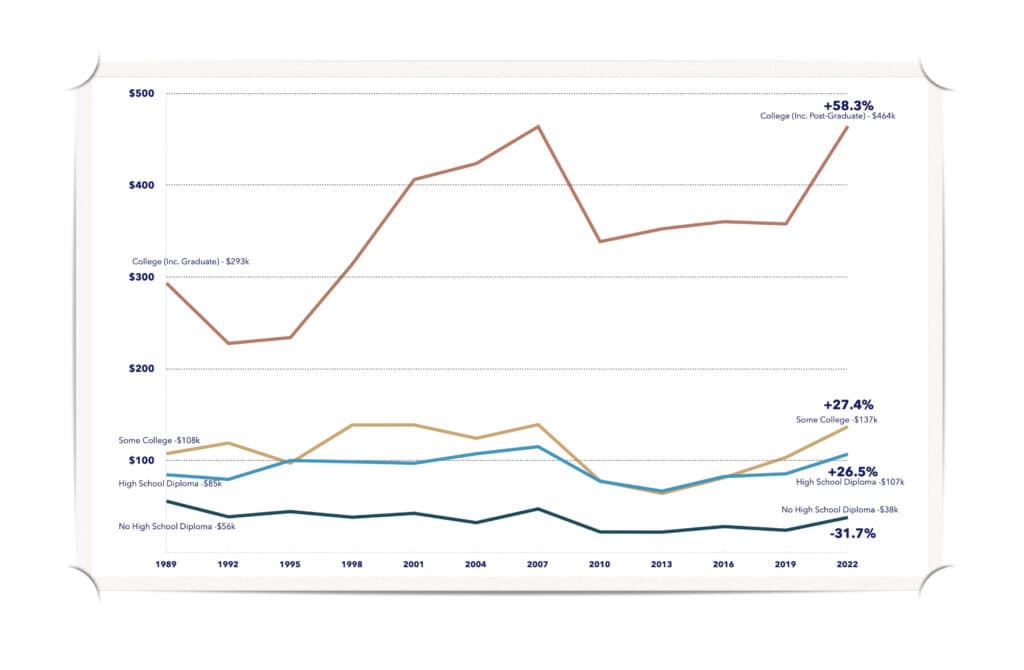

The abstract is even more up front: “We document the emergence of a substantial college wealth premium since the 1980s, which is considerably larger than the college income premium. Over the past four decades, the wealth of college households has tripled. By contrast, the wealth of noncollege households has barely grown in real terms over the same period.”

The above chart is typical of the observation. Wealth and Income of College Households outstrip non-college!

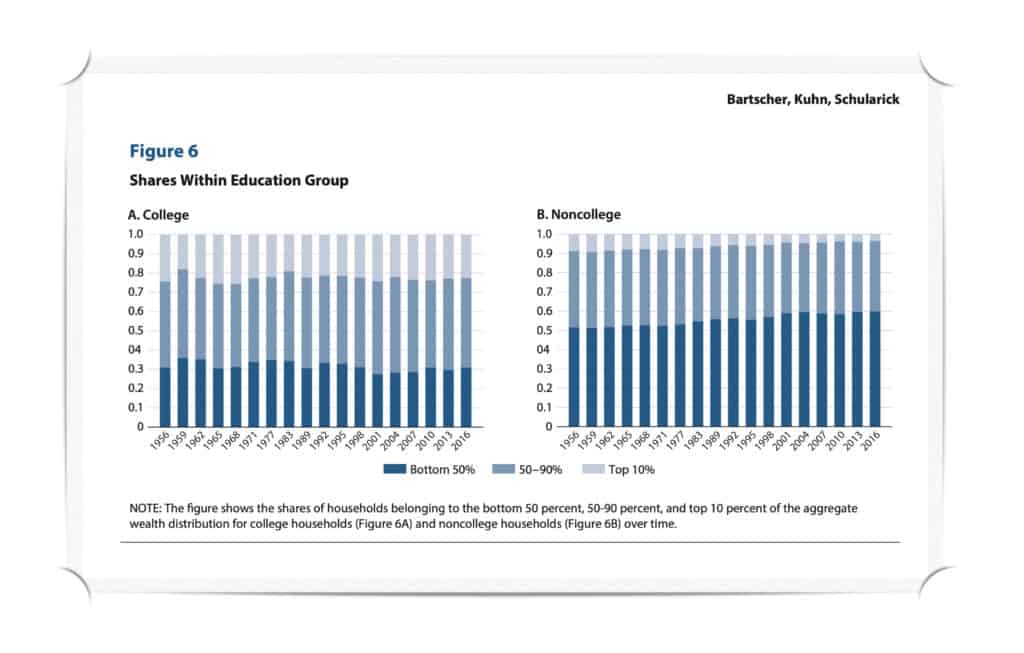

On the attached chart, you will find the other wealth distribution chart that is used. An observer tuned to the college premium story notices that far fewer college households (approximately 30%) are in the bottom 50% of US household wealth than non-college households (approximately 60%).

A curious observer might pose a different question. Why are 30% of college households still in the bottom 50%? Before suggesting the mere absence of college is the cause, one should explore if there are other causes, perhaps more effectively driving the difference.

The college households include those with advanced and professional degrees. A failure rate of 30%, with college households still occupying the bottom 50% of the wealth distribution, either suggests a flawed analysis or that a high proportion of college households still have risk factors that result in lower wealth.

The researchers allude to this in their additional insights later:

“Looking at who makes it to the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution, we find that the share of noncollege households in the group has declined over time (Figure 2). By contrast, the share of college households making it to this group has remained remarkably stable over time. Our results therefore suggest that obtaining a college degree does not increase the probability of making it to the top 10 percent. A college degree seems to help households to keep pace, but not to reach the top.”(1)

“While we document a sharply rising college wealth premium in recent decades, it is important to note that causality can run in both directions. College graduates may hold more wealth due to their higher educational attainment, but there is also evidence that it is easier to obtain college degrees when coming from a wealthy family (see, e.g., Pfeffer, 2018, and Pfeffer and Killewald, 2018).”(1)

The Federal Reserve report in 2018 titled The Financial Returns from College across Generations: Large but Unequal summarizes it best:(2)

“We document three important ways in which inherited demographic characteristics influence family income and wealth:

- The head-start effect. Families headed by someone with certain “favorable” inherited demographic characteristics typically earn much higher incomes and accumulate much more wealth than families without these characteristics.

- The upward-mobility (or exceeding-expectations) effect. For families headed by someone with less advantageous inherited demographic characteristics, completion of a four-year degree typically boosts income and wealth far above the levels they would have achieved without a degree. These families move up the income and wealth rankings (relative to levels predicted by their inherited demographic characteristics) more than do college grad families with more favorable inherited characteristics.

- The downward-mobility (or falling-short) effect. Finally, we show that family heads with college-educated parents who are downwardly mobile in educational terms suffer notable negative consequences; these are people who do not finish college even though their parents did.

In other words, if you were wealthy, you generally had higher incomes and generated more wealth (#1), unless your child struggled academically (#3). And, if you were not wealthy, have grit and excelled academically, you could do better than even the wealthy(#2).

So far, we have a weak argument that the absence of a college degree is the problem. Maybe there are characteristics of people who have college degree, such as their wealth, that contributes to wealth, more so than the college degree itself.

Misleading Framing

Researcher bias and the way they analyze and present data can lead to conclusions that may be misleading.

In the conversation of college versus non-college households, there is a particular attraction to framing stories around an ethnicity or gender narrative because there are dramatic differences in the results when those lenses are used.

Whether that lens appropriately identifies the root cause is a critical determination that researchers should pay more attention to.

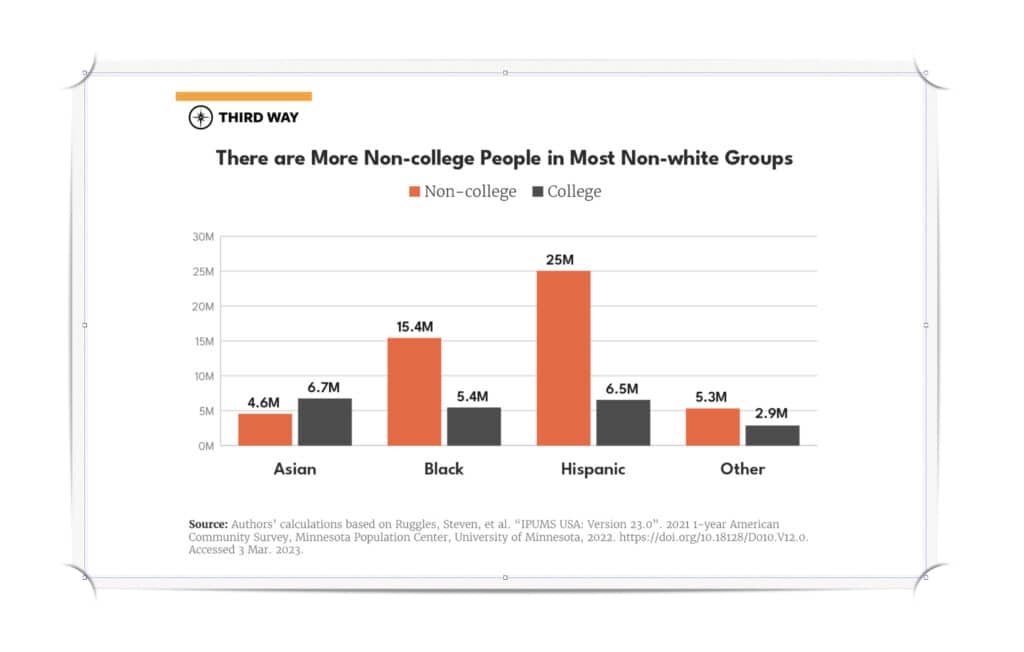

Here is a typical example of the flawed or misleading presentation of data. The researchers say: “Except for Asian Americans, there are more Americans of each race without a four-year degree than there are those with one.”(4)

The following chart accompanies this statement. It says There are More Non-College People in Most Non-white groups.

If non-college households are a problem, what does the chart frame as the primary challenge?

What does it say about whites?

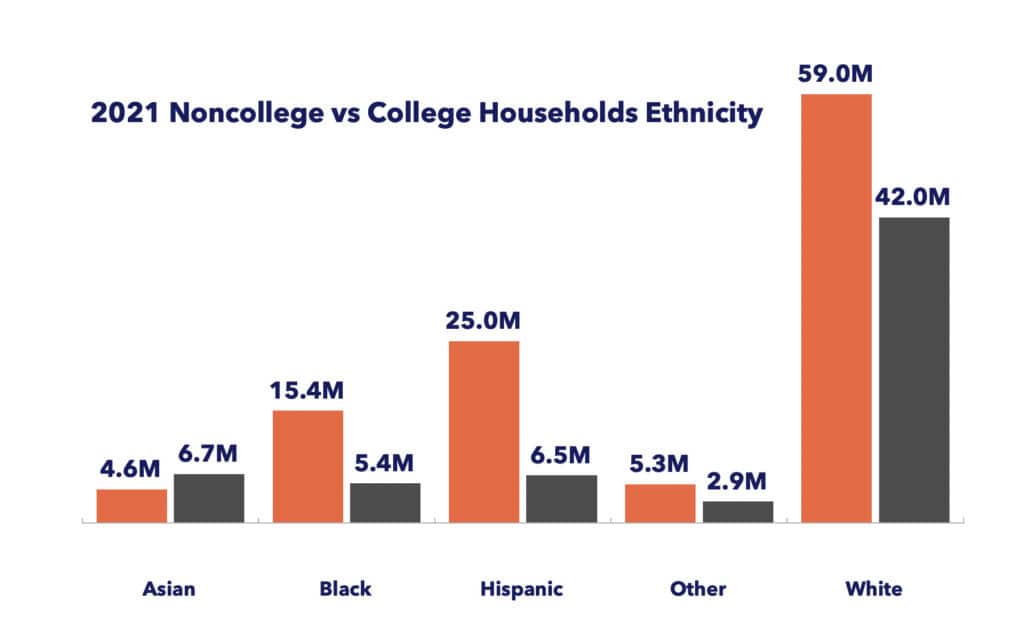

Here is what that chart looks like when it fully includes white households.

When fully presented, a few things should stand out:

- Asians have more in college than non-college. Why? What can we learn from that group?

- The largest non-college group by far is the white.

- Whites with 59M have more non-college than people of color who are non-college (42 million).

We ought to address the question by trying to understand the underlying characteristics that are root causes, rather than the framing around narratives.

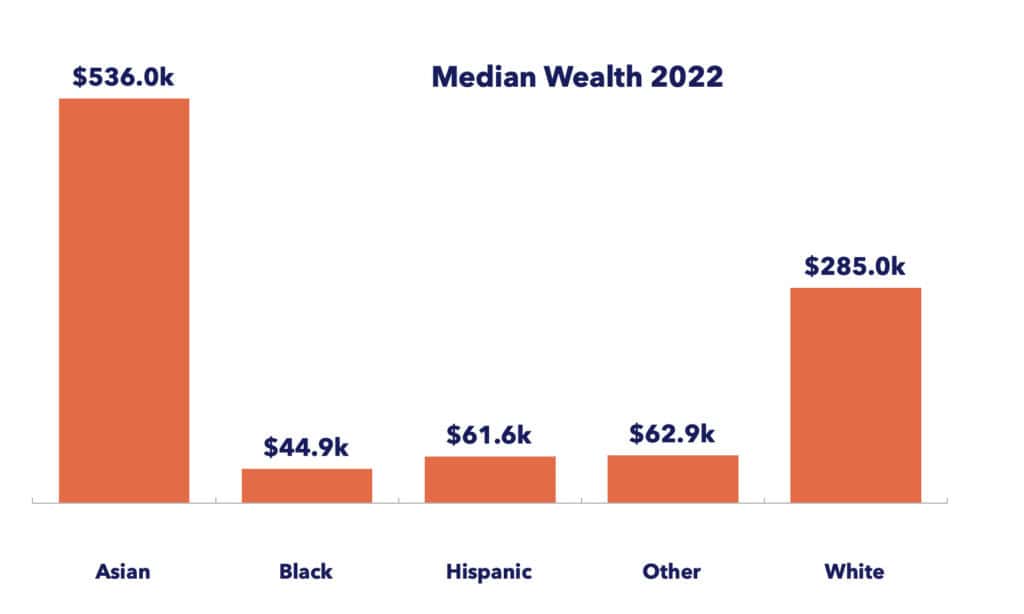

Here is another reason we might wish to learn about Asians:(7)

One more example from the same report.

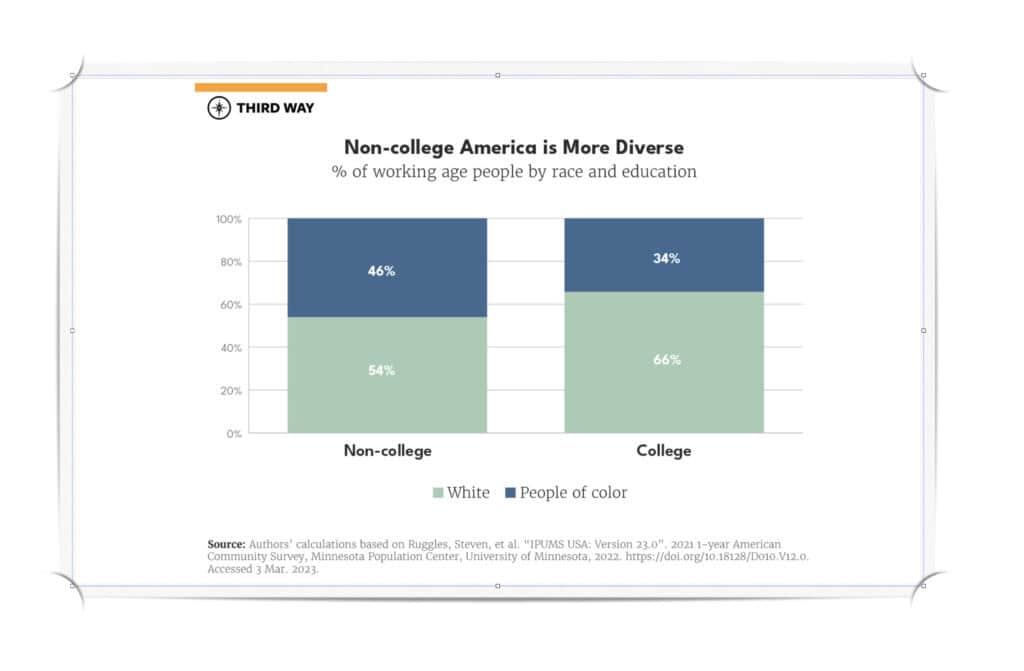

The chart asserts that Non-college America is more diverse because it has fewer whites. Should we assume that College is bad because it makes us less diverse? Should we avoid sending people to college if we want more diversity in society?

Silly reasoning. We agree. Researchers have an obligation to use data and the conclusions they draw more responsibly.

Before we suggest college as the solution to all our problems, we should consider whether and when college really fixes the underlying problem.

Let’s explore some alternate explanations of wealth.

Financial Literacy

In a section titled Financial Literacy and returns on Wealth, the Federal Reserve researchers point out: “Our results suggest that stock market exposure and business ownership are driving forces behind the rise in the college wealth premium.”(3) And, “One reason why college households hold different assets may be financial literacy.”

We agree. As pointed out in other chapters, even wealthy parents struggle with financial literacy, opting for lower-return prestige colleges. Financial literacy is essential when considering whether college would make a good investment.

More importantly, improving financial literacy does not require hefty investments in college degrees, nor does stock market exposure or business ownership generally.

Inheritance

Just one variable — how much you inherit — can account for more than 60 percent of U.S. wealth inequality, according to economists Pedro Salas-Rojo at the International Inequalities Institute at the London School of Economics and Juan Gabriel Rodríguez of the Complutense University of Madrid, who applied machine learning to previous editions of the same Fed data. (5)

A recent Federal Reserve report suggests the inheritance effect may be lower, at the 13 to 16% level. But we find many issues with he methodology used and conclusions reached. (6)

Who is receiving an inheritance?

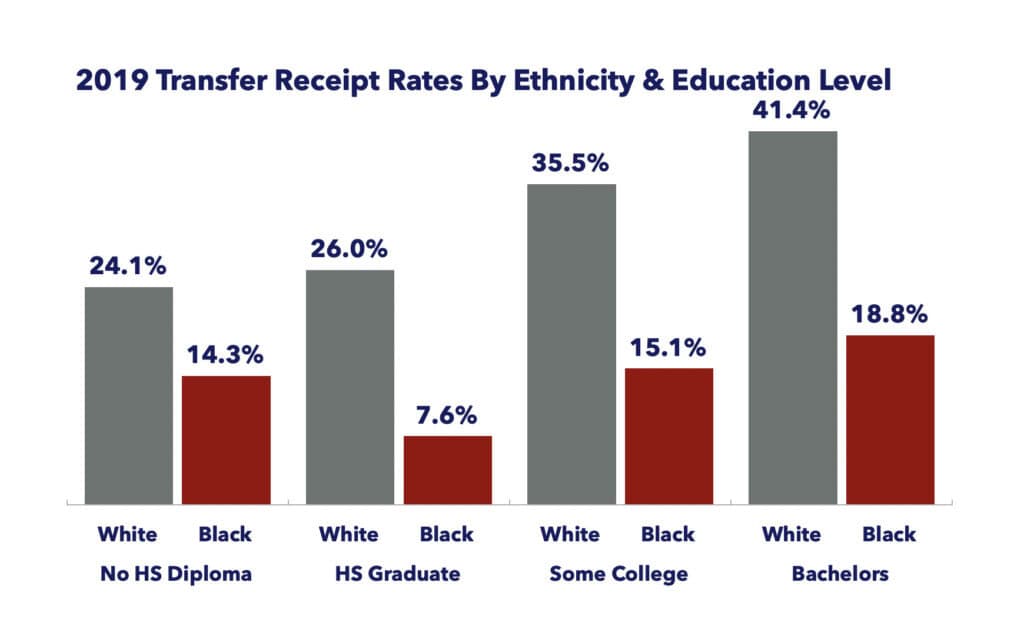

College graduates are the highest recipients of inheritances. Just look at the chart, which shows that regardless of the ethnicity of the recipient, bachelor’s degree holders receive inheritances more often than others. (7)

If college degree holders receive inheritances more often, then their reported wealth should be higher. That does not mean it should be attributed to their college degree, though. It might have more to do with who they are getting their inheritances from.

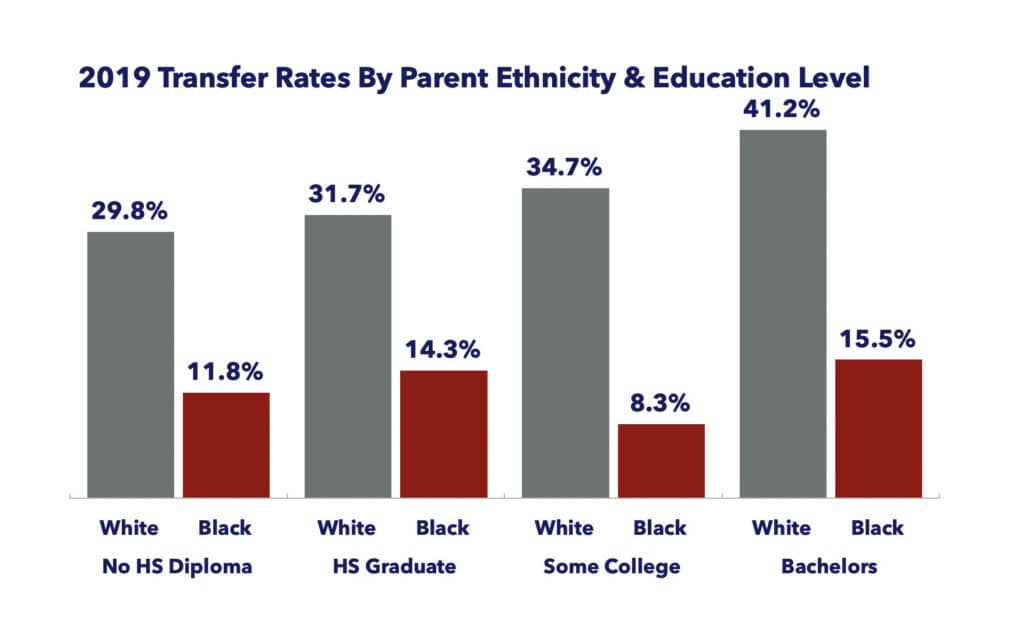

Who is leaving an inheritance?

The same is true for those who are leaving the inheritances!

We presume that college degrees were historically a pathway to wealth. Wealthy parents could afford to send their kids to college, and academically excellent students who received scholarships or invested in college found themselves on an incremental wealth track.

We also show elsewhere that the current conditions of college costs and wages do not imply that this generation will have favorable results.

Over the last few decades, the conditions of college being largely value drivers have shifted. We know that in 2012, when we first started this evaluation, it had already shifted.

Those parents followed in the traditions of parents historically. They purchased college degrees for their children. But more importantly, as shown in the chart above depicting who is leaving inheritances, they also left them some portion of their wealth.

We are back to whether the analysis of college versus non-college wealth tells us anything about college degrees’ current/future value. So far, we have not seen the evidence in the analysis that a college degree will convincingly deliver better results if you are not wealthy or academically gifted.

Before we wrap up the wealth analysis, we need to explore the hidden inheritance, the gift every college graduate receives, which may be, in many cases, a socially subpar investment.

The hidden inheritance

With rare exception, every college student receives a significant monetary gift they never have to repay. Whether those gifts appear in the graduate’s wealth is a function of how well a college education translates into higher income.

The rare exception? A college student who pays the full cost to attend from their savings and loans.

We need to explain.

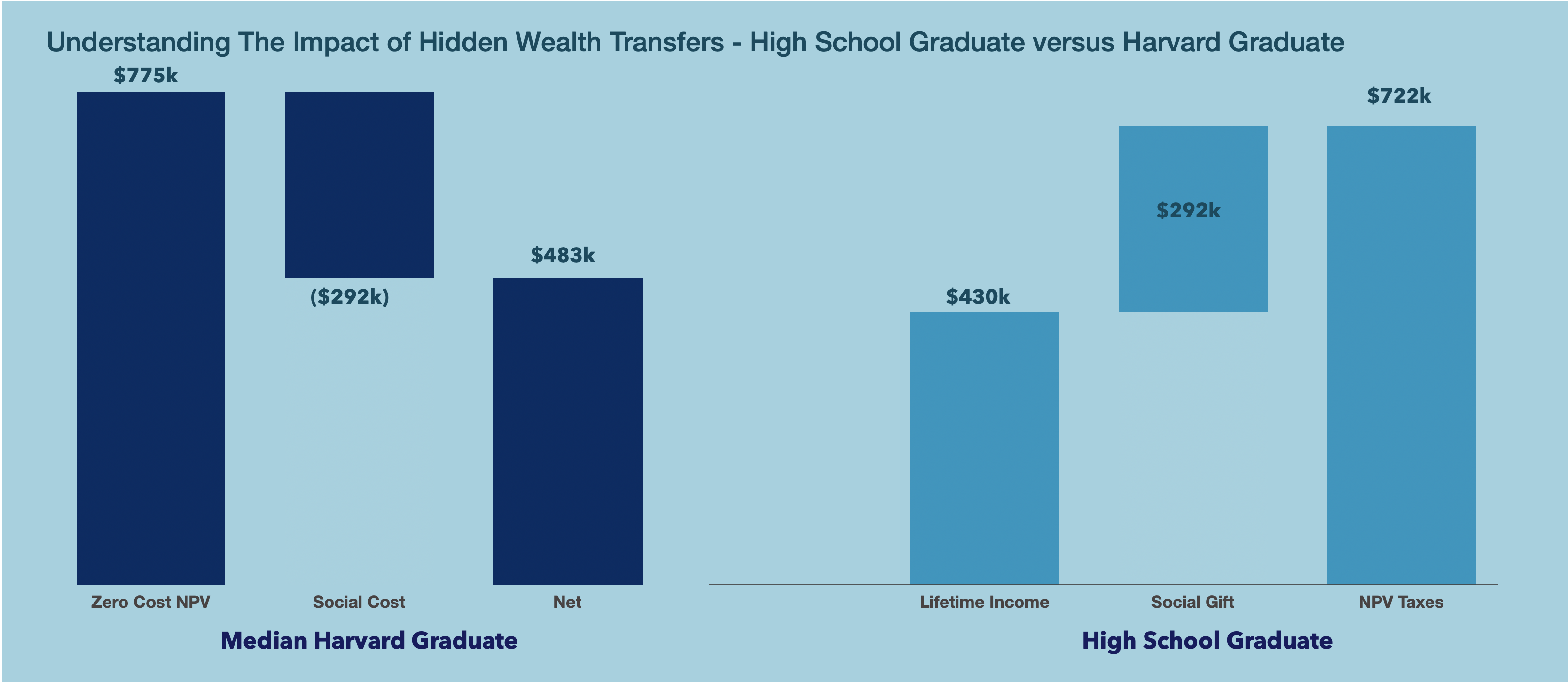

A four-year Harvard degree has an NPV full cost of approximately $300k.

- Harvard receives approximately $300k for every student, regardless of what the student pays directly. The rest comprises payments by others, including donors or the government.

- If the parents pay all those fees, not as a loan to the student, then the student receives a $300k gift.

- If the parents or student pays nothing, the student receives a $300k gift. The costs are paid to Harvard by donors or through government grants.

The student’s direct responsibility, including their loans, is the only cost that shows up in their wealth accounting. The difference between what the student pays directly and the $300k full cost is a wealth transfer, a gift that the college student receives that they never have to repay.

Economists love to point out how net costs are much lower than full costs, but they ignore the fact that the difference between net costs and full costs is also a social cost in the form of a hidden wealth transfer.

No high school graduate who does not go to a subsidized education program receives these gifts. Indeed, these gifts alone could explain the difference between college and no college wealth.

Let’s use an example with the median Harvard Graduate shown below. We assume the college student pays nothing, and their lifetime earnings are worth $775k. The social costs of $292k were not shown in the student’s wealth account. The net social benefit is $483k. The High School graduate has a much lower lifetime income of $430k. However, if they had received that $292k social gift, their net worth would climb to nearly the same value as the Harvard graduate!

Conclusion

Researchers think the wealth premium, like the college premium, might be useful devices for compelling support that college degrees are overwhelmingly valuable.

We do not.

We have pointed out that preexisting wealth, academic excellence, visible inheritances, and hidden inheritances may have more to do with the observed wealth differences than the college degree value itself.

Cast an eye on the attached chart. It’s a standard chart used by wealth researchers and shows wealth over time by educational attainment.

The researchers see the gap between college and non-college as the main priority. The entire preceding discussion should have explained why this occurs without clearly making the case that college is a low-risk path to wealth.

More importantly, when we look at the chart, we see some interesting insights:

- There is very little difference between some college and a high school graduate. Considering hidden inheritances, one concludes that the college is good even if you don’t complete it crowd is wrong.

- The biggest wealth challenge we face as a country is the problem of households not completing a high school diploma!

Reference Sources

- Alina K. Bartscher, Moritz Kuhn, and Moritz Schularick. “The College Wealth Divide Continues to Grow.” Economic Synopses, No. 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.20955/es.2020.1

- Emmons, W.R.; Kent, A.H. and Ricketts, L.R. “The Financial Returns from College across Generations: Large but Unequal.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis The Demographics of Wealth 2018 Series, 2018, Essay No. 1; https://www.stlouisfed.org/household-financial-stability/the-demographics-of-wealth/the-financial-returns-from-college-across-generations.

- Alina K. Bartscher, Moritz Kuhn, and Moritz Schularick, “The College Wealth Divide: Education and Inequality in America, 1956-2016,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, First Quarter 2020, pp. 19-49. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.102.19-49

- Colavito, Anthony, Joshua Kendall, and Zach Moller. “Worlds Apart: The Non-College Economy.” Thirdway.Org. Third Way, May 19, 2023. https://www.thirdway.org/report/worlds-apart-the-non-college-economy.

- Van Dam, Andrew. “How Inheritance Data Secretly Explains U.S. Inequality.” Washingtonpost.Com. Washington Post, November 10, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/11/10/inheritance-america-taxes-equality/.

- Sabelhaus, John, and Jeffrey P. Thompson. “The Limited Role of Intergenerational Transfers for Understanding Racial Wealth Disparities.” Bostonfed.Org. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, March 7, 2023. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2023/the-limited-role-of-intergenerational-transfers-for-understanding-racial-wealth-disparities.aspx.

- NOTE: We mention this report here because of its recency, and finding that suggests inheritance may have a lower effect than we hypothesize. We have issues with the report, methodology and findings.

- The above capture illustrates some of the challenges. Wealth will be heavily influenced by age, years at work, whether the household is single or married. The most effective comparison of college impact on. lifetime would look at the subset of households that have had the full lifetime and compare college and noncollege. However, looking at households over 65 would represent folks that graduated from college some 40 years ago. This is likely a period when college degrees were substantially value creating, versus today’s environment. We have pointed out elsewhere our concerns about the measurement of lifetime earnings and shown how the value proposition shrinks over time.

- We contend the wealth analysis shows a lot more than the value of college and is not indicative of whether a current college degree will turn out to be more valuable in the long term.

- Aladangady, Aditya, Andrew C. Chang, and Jacob Krimmel. “Greater Wealth, Greater Uncertainties: Changes in Racial Inequality in the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federalreserve.Gov. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October 18, 2023. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/greater-wealth-greater-uncertainty-changes-in-racial-inequality-in-the-survey-of-consumer-finances-20231018.html.