When does it make sense to use debt to finance higher education? Did the 42 million American who have borrowed $1.63 Trillion make the right decision? Is there a way up front to know if borrowing to finance college is a good idea?

Read on to find out.

“Debt is a trap, especially student debt, which is enormous, far larger than credit card debt. It’s a trap for the rest of your life because the laws are designed so that you can’t get out of it. If a business, say, gets in too much debt, it can declare bankruptcy, but individuals can almost never be relieved of student debt through bankruptcy.”

Noam Chomsky

The wealthy use debt as leverage to make more money. For example, if your investments generate 8% returns, and you can borrow money at 6%, then the investor would borrow and invest. To buy something big, it’s better for them to use debt than to liquidate their investments.

That’s not the same for the financially challenged. If you don’t have an excess of assets and income, debt is used to acquire something you couldn’t ordinarily afford. You would do so if the benefit of the additional spending exceeds the cost, including debt expenses.

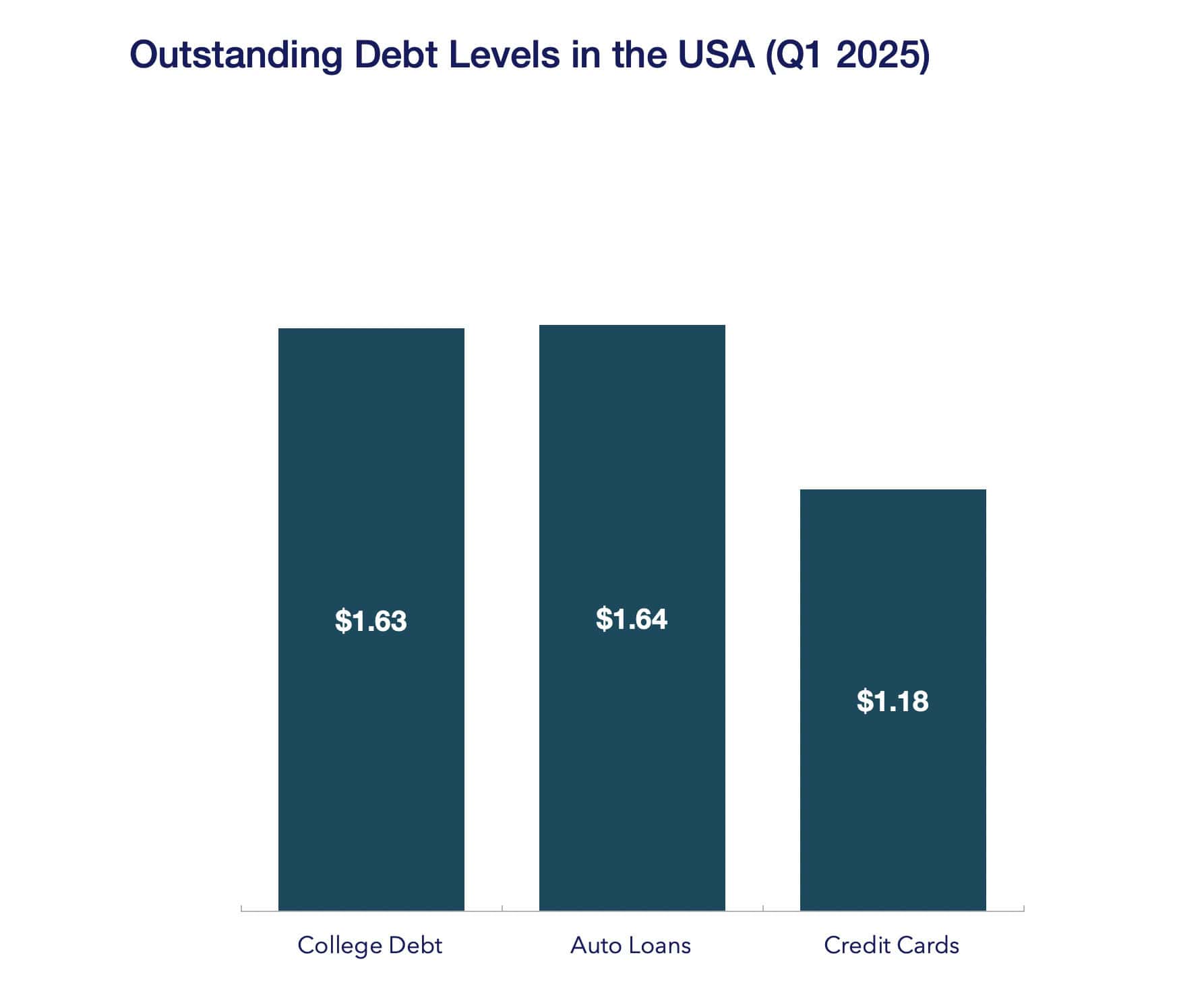

This is risky for educational debt since it cannot be removed even if the borrower declares bankruptcy. Yet, educational debt has grown dramatically and will stand at $1.63 trillion in 2025.(1) This is 38% higher than total credit card debt and almost equal to Auto Loans.

Is this high educational debt good for America, the families and students using it, and the students themselves? When does it make sense to use debt to finance education?

American Higher Educational Debt Cases

Students and families with significant assets or wealth rarely use government-sponsored or subsidized debt. They may not qualify. So, we should assume the following more realistic scenarios:

- Anton has decent grades and was accepted into several institutions. Because he and his family are financially challenged, he will receive a Pell grant of about $9,000 annually. He does not have an offer that covers full attendance. His lowest-cost choice requires $10,000 per year from Anton and his family. Anton and his family cannot afford the $10,000 and will have to borrow to attend college. Does borrowing make sense for Anton to attend college?

- Alice, like Anton, has good grades and was accepted into several institutions. She will receive a Pell grant of about $9,000 annually. Alice has narrowed her choices between a state school and a private college. Both will provide scholarships and grants that she will not have to repay. Her academic standing does not qualify her for an entire free ride at either school. The state school will cost $10,000 annually, and the private school an extra $20,000. She and her family can afford the $10,000 but must borrow to attend the private school. Does borrowing make sense for Alice to go to the more expensive school?

Each of these cases is a fundamental decision that many financially challenged Americans make regarding their choice to attend college: in one case, whether to attend, and in the other, whether to upgrade their choice.

Both of these choices matter to the students and their families. Both presume college is a good investment. But should we make that assumption?

The College Investment Assumption

The notion that college is generally a good investment is fatally flawed. That view leads to a higher degree of debt to attend college than would otherwise occur.

Some college degrees are incredible investments. Others could be better.

A college investment is a considerable commitment and must receive the requisite due diligence. This means thoroughly researching and understanding the potential return on investment for the chosen degree.

One should never consider debt funding for a college degree if that degree will not provide a good return on investment. It’s important to remember that not all college degrees are equal regarding return on investment.

Consider this: Would you take out a mortgage to buy a house if you expect the house’s value to decline? This thought-provoking question applies to your college investment as well.

Why should anyone borrow money to invest in a losing college proposition?

First, start with ROI

Choosing a college is a complex decision that requires weighing other viable options. This approach broadens your perspective and ensures you make the best decision for your future.

- Your base benchmark is graduating from high school and going to work.

- Next are technical, trade, or apprenticeship programs where one can work while gaining a specialty skill.

- Associate or Certificate programs are lengthier and could require giving up the work option, but they are shorter than the Bachelor’s.

- Do you attend full-time to minimize your time until graduation, or would you trade off having the ability to work longer until graduation?

- Are you interested in a post-graduate role? If so, you will need the necessary prerequisite undergraduate foundation.

- For all choices beyond high school, you will have multiple institutional offerings with varying cost impacts.

Finding the choice that best fits your needs and is an optimal investment is in your best interest.

Pick the best long-term outcomes that require your lowest financial contribution.

Please read our article on How to figure out a College Return on Investment again.

Understanding debt

Debt is a method of paying for your investment up front. It delays the payments you make, but it does not reduce the price.

If your investment generates a return higher than your cost of debt, then the debt makes sense.

Why, then, do we see so many complaints about college debt?

The answer is quite simple. Too many assume that college returns are positive or higher than the cost of debt. They are not always, and you should avoid them when it isn’t.

The inability to repay college debt is directly related to the subpar returns of some college degrees.

JB is a 40-year-old living in Illinois. With a Master’s degree and 12 years of teaching experience, JB makes about $53k a year and has $70k in unpaid college debt.

The median college student today has a salary of $50,806 (measured ten years after enrollment) and has paid approximately $85k for four years.(1) Our college investment model calculates the Net Present Value of Lifetime earnings after costs and taxes, and tells us that the median student must have a comparable salary of $58,063 to break even with the median high school graduate. Thus, the median college degree is a subpar investment.

JB is earning well below the breakeven, 12 years after leaving college, has also earned a Master’s degree, and likely paid more than the median costs due to those extra years. JB’s college return is below that of the median college graduate. No wonder JB is having difficulty with the college debt.

JB’s annual salary of $53k results in take-home pay of $44.5k after federal taxes, which will be lower when considering Illinois taxes. To pay off the loan in 20 years, when JB is 60, a $462 monthly payment is required (assuming a 5% interest rate), 12.5% of take-home pay. JB will struggle to pay off that debt!

Sadly, in America today, millions of JBs have subpar college investments and debt that will be difficult, if not impossible, to repay.

Worse, we continue to add to this list each year.

How did we get here with our Debt Balance?

In its report titled Buyer Beware – First Year Earnings and Debt for 37,000 College Majors at 4,400 Institutions, the Georgetown University Center of Education and the Workforce makes the following observations:(3)

- 27 percent of workers with an associate’s degree earn more than the median for workers with a bachelor’s degree,

- 35 percent of workers with a bachelor’s degree earn more than the median for workers with a master’s degree,

- 31 percent of workers with a master’s degree earn more than the median for workers with a doctoral degree, and

- Twenty-two percent of workers with a master’s degree earn more than the median for workers with a professional degree.

When it comes to choosing what to study and where to study, buyer beware.

Despite this incredible variability, the CEW, in its College Payoff report, frequently quoted by researchers, says:(4)

“No matter how you cut it, more education pays.”

They say, “Over a lifetime, individuals with a Bachelor’s degree make 84% more than those with only a high school diploma.“

They also conclude: “The difference in earnings between those who go to college and those who don’t is growing, meaning that postsecondary education is more important than ever.“

There are some qualifications for these findings in their reports, but these are nuances that few get to.

The CEW approach reflects the optimistic sentiment and communication about college outcomes and understates the risks.

The Federal Reserve says the same. College Administrators, Economists, and many other smart people echo this sentiment.

Too many vital voices overlook the challenges of generating a good return and, as a result, reducing concerns about the risk.

That optimism reduces the due diligence required of college investors. The result is far more bad decisions to pursue subpar college degrees, even if they involve debt.

The wealthy and well-off are equally misled in interpreting the value of higher education. However, their financial situation makes investment losses palatable. Indeed, the investment losses are invisible to many, including policymakers and educators. What do we think happens when the financially challenged ask for advice or consider a college education for their child? The people they seek advice from are unaware of the risks and ubiquity of subpar college investments.

Without improvements in financial literacy, expect the college debt crisis to grow.

Does College Debt make sense?

Let’s return to our two cases.

For Anton, the first question is whether his college choice is a good investment. Does this choice provide a return greater than that of a high school graduate? Borrowing to invest in a program that delivers subpar returns is a recipe for continuing financial jeopardy. If it does, debt should be considered; if not, look for alternatives that generate a good return. Those may include an associate’s degree, community college, an internship, or an apprenticeship. All of these are viable and valuable choices.

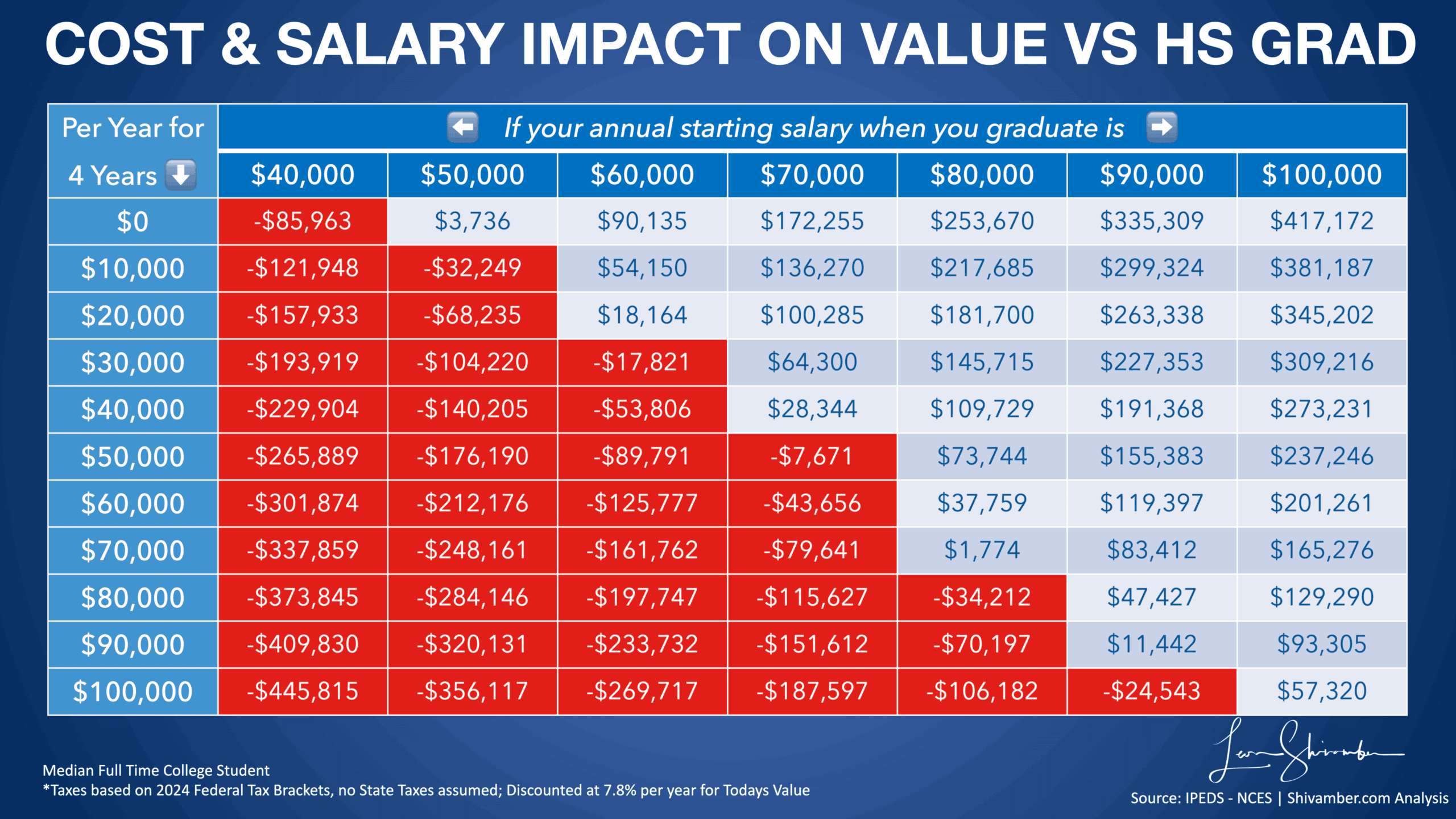

Anton should calculate the ROI for his chosen field of study at his selected college using our proposed approach (Net Present Value of Lifetime Income after cost and taxes). We have provided a sample spreadsheet and instructions for doing so. For our discussion here, we have a temporarily relevant shortcut (the underlying assumptions change over time, which is why you need to use the spreadsheet method). Based on the current macro assumptions, we present the following chart, which compares salary and cost assumptions for a given choice and a high school graduate. For example, if a student expects to earn $40,000 when they graduate from a four-year program and attend college free of cost ($0 annually), their return is estimated at $85,963 below a high school graduate who went to work. That student would have to earn a starting salary of $50,000 to exceed the breakeven (by $3,736).

Taking Anton’s choice of $10,000 annual costs to attend college, we find that the break-even lies somewhere between $50,000 and $60,000 starting salary (the spreadsheet provides a precise number, but let’s assume $54,000). If the college has a track record of placing students in Anton’s chosen field of study with starting salaries above $54,000, then we can say that the college delivers a good ROI. Our model uses a 7.8% discount rate, so debt makes sense if earnings are above $54,000 and the loan rate is below that rate.

Alice should first evaluate the choices as investments before the question of debt. Which college return on investment is better? You may be surprised that sometimes, higher-cost colleges have better returns if the costs are not significantly higher, but the graduating students earn dramatically higher wages. The reverse can also be true. The school with the better return should be chosen, as long as the investment return is higher than that of a high school graduate.

Using our handy cheat sheet, let’s assume that Alice’s state college, which costs $10,000 annually, has a track record of graduating students in her field of study with salaries of $60,000. In that case, the ROI provides a net benefit of $54,150 over a high schooler. If the private school with $30,000 annual costs has a track record of $70,000 graduating salaries, then the ROI net benefit is $64,300. This will make the private school a better choice despite the extra fees. On the other hand, if starting salaries from the private school are not noticeably better, say $60,000, that would generate an ROI loss of $17,821. Not a good idea!

The shortcut gives you some sense of the tradeoffs between colleges based on their costs and earnings outcomes. The best way to fully reflect a student and family’s unique choice is to research it, find the relevant data, and calculate the return on investment.

Pick the solution that generates the best positive return over a high school graduate, and where you will excel. If all your choices are subpar investments, that is negative ROI relative to a high school graduate, then debt should not be considered. Look for other alternatives as we have outlined above.

College Debt is an Investment – treat accordingly

The decision to invest in a college education is complex and significant, requiring careful consideration.

While some degrees can be precious investments, others may not provide a good return.

Assessing the potential return on investment for any college degree before taking on debt to fund it is paramount.

Improve financial literacy around college choices, or be prepared for more debt forgiveness!

Reference Sources

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York Center for Microeconomic Data: Household Debt and Credit Report (Q1 2025). https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc

- U.S. Department of Education College Scorecard. https://collegescorecard.ed.gov

- Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, Buyer Beware: First-Year Earnings and Debt for 37,000 College Majors at 4,400 Institutions, 2020. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/collegemajorroi/.

- Anthony P. Carnevale, Ban Cheah, and Emma Wenzinger. The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2021. cew.georgetown.edu/ collegepayoff2021.

Read More In This Series

Next

A Critical Analysis of College ROI Research – Georgetown University The College Payoff