McKinsey research shows that asking the wrong question leads to solving the wrong problem.[1] And right now, America is asking, “How do we stop foreign workers from taking jobs?” when we should be asking, “Why are we producing millions more graduates in fields the economy doesn’t need, and not producing those the economy wants?”

Think you can frame problems effectively? Would you make better decisions than your elected officials? Let’s find out.

“The moment we want to believe something, we suddenly see all the arguments for it, and become blind to the arguments against it.”

George Bernard Shaw

- Why Smart People Solve Wrong Problems: The Forces That Lead Even Brilliant Leaders Astray

- Four Systematic Forces Push Leaders Toward Wrong Solutions

- H-1B and OPT Programs Aren’t Broken, They’re Rigorous, Adjudicated Processes With Real Oversight

- The Senator’s Dilemma, And Why Our Leadership Needs Better Support

- Visa Workers Account for 1 Million Jobs, The Crisis Affects 25 Million Graduates

- Nearly 25 Million College Graduates Face Unemployment or Underemployment

- Even Eliminating Every Visa Worker Would Address Only 4% of Affected Graduates

- Even Narrowing to STEM Fields, Visa Workers Explain Only 12% of Graduate Struggles

- The CS Paradox: 3.55x More Visa Workers Than Affected Graduates, Yet Only 6.1% Unemployment

- Domestic Oversupply and AI Automation, Not Visa Competition, Explain CS Graduate Unemployment

- The Senator’s Key Evidence Rests on 75 Survey Responses, With a 1.7% to 13.9% Confidence Interval

- China Graduates 4.5x More STEM Students Annually, Visa Programs Are How America Retains Competitive Advantage

- America Faces Critical STEM Shortages While 25 Million Graduates Struggle, Because We Train for the Wrong Fields

- Restricting Visas Sacrifices Talent Retention and Competitive Advantage, For 4% of the Problem

- Solving the Crisis Requires Visa Program Fixes, Not Elimination, Plus Comprehensive Higher-Ed Reform

- Target Documented Abuse Through Wage-Based Selection and Enforcement, Keep Talent Retention Mechanisms

- Require Outcome Transparency, Gainful Employment Standards, and Strategic Workforce Development

- No Major Policy Vote Without Comprehensive Analysis of Scale, Root Causes, and Unintended Consequences

- Restricting Visas Won’t Solve the College Employment Crisis; It Requires Harder Work: Higher-Ed Reform

- Smart Leaders Deserve Better Analytical Support—And Political Space to Change Their Minds

- This Isn’t Just Policy; Every Organization Faces the Same Wrong-Problem Risk Without Dissent Culture

- Reference Sources

You’ve just been elected to the U.S. Senate. Congratulations. Now here’s your first crisis:

A constituent, a physics graduate, sharp and hard-working, can’t find a job. Their parents are furious. They spent four years and invested $150,000 in that degree. Then another email arrives. And another. Engineers, computer scientists, mathematicians, all struggling. Your inbox is flooding with stories of American graduates losing out.

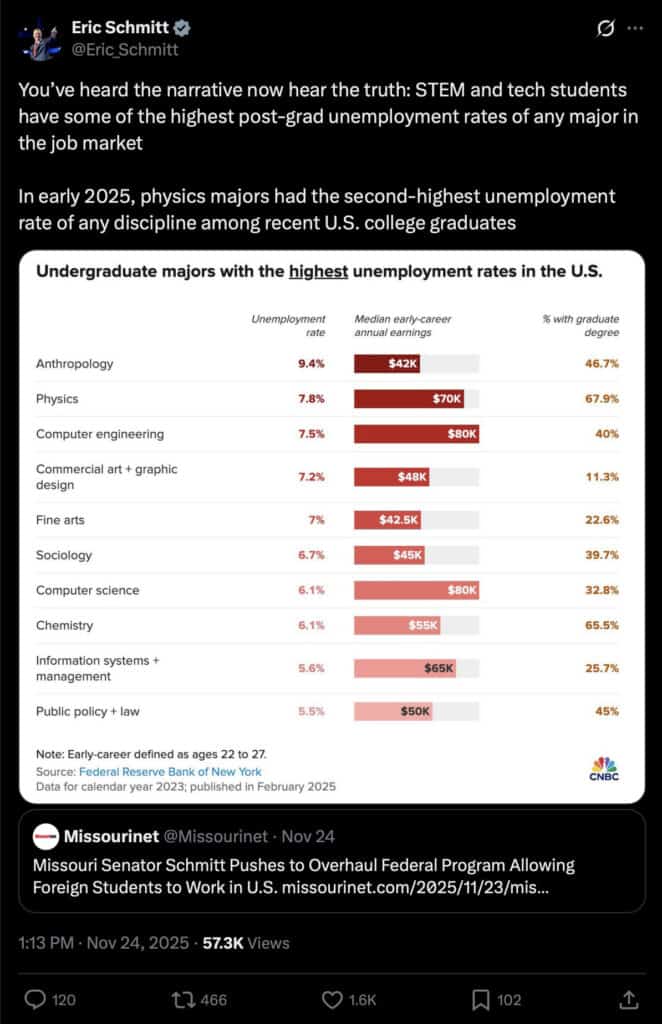

You check the Federal Reserve data. Physics graduates face 7.8% unemployment—second-highest among all majors.[3]

Your staff pulls more numbers: foreign workers on H-1B and OPT visas hold roughly 1 million jobs in America.[19][20] The connection seems obvious.

What would you do?

If you’re thinking “restrict those visa programs and protect American workers,” you’re not alone. That’s precisely what is being proposed as you read this in 2025.[2] It’s intuitive. It’s visible. It shows you’re taking action.

There’s just one problem: 25 million American college graduates are struggling to find appropriate jobs.[17][18] Even if you eliminated every single visa holder tomorrow and perfectly replaced each one with an American graduate (economically impossible, as we’ll see), you’d help at most 4% of them.

Where do the other 23 million go?

Still confident in your decision? Or are you starting to suspect there’s something deeper going on, something that easy answers won’t fix?

This isn’t a story about one senator making one mistake. It’s about how smart people, facing enormous pressure to act and limited time to analyze, end up solving the wrong problem while the real crisis goes unaddressed. It’s about the forces that lead even brilliant decision-makers astray.

And it’s about why the most challenging problems demand that we resist our instincts and ask better questions.

Why Smart People Solve Wrong Problems: The Forces That Lead Even Brilliant Leaders Astray

In November 2025, Senator Eric Schmitt pointed to physics graduates’ high unemployment rate as evidence that foreign workers are taking American jobs.[2] He’s not wrong to be concerned—American graduates genuinely are struggling. But he’s looking at the wrong cause.

The senator isn’t acting in bad faith. He graduated cum laude, earned a law degree, served as Missouri’s Attorney General, and now represents millions of constituents.[4] He’s an intelligent person facing what all leaders face: a genuinely challenging situation, public pressure to do something, a complex system most experts don’t fully understand, and limited time to become an expert himself.

That’s the human condition of leadership. It’s also precisely why we should demand better analysis.

Four Systematic Forces Push Leaders Toward Wrong Solutions

Several powerful forces push even intelligent leaders toward wrong conclusions:

- The Story-Over-Data Trap: A vivid narrative, such as “my constituent lost a job to an H-1B worker,” feels more real than a large and abstract statistical pattern you haven’t seen visualized. We evolved to learn from stories. But policy should be built on facts, analysis, and statistical patterns, not anecdotes.

- The Visibility Bias: Foreign workers are visible and easy tp target. The broken university system that steers 130,000 students annually into psychology (when the market needs only 12,000, most of whom require expensive graduate degrees)[5] is invisible and diffuse. Politicians get credit for visible action, not for fixing invisible systems.

- Ideology Over Analysis: For some politicians, opposing immigration is a core principle. For others, defending free markets is foundational. Both camps have investments that make dispassionate analysis difficult. When your worldview already suggests visa programs are bad (or good), confirming evidence attracts attention while disconfirming evidence gets dismissed.

- The Analyst Gap: Most senators have limited analytical infrastructure for deep policy work. A good senator has 3-5 expert staffers who genuinely know visa programs or higher-ed economics. They’re competing for attention with a hundred other issues. There is not enough capacity to conduct the rigorous root-cause analysis this kind of problem requires.

The result? Smart people point at physics unemployment without understanding what’s actually happening in physics labor markets. They propose solutions that help 4% of affected graduates while potentially undermining American competitiveness in a global talent war.

This isn’t unique to this senator, his followers, or this issue. It’s systemic and rampant in critical decision-making.

H-1B and OPT Programs Aren’t Broken, They’re Rigorous, Adjudicated Processes With Real Oversight

Before we can evaluate whether H-1B and OPT programs are “broken,” we need to understand what they actually are. Most public debate skips this part entirely.

H-1B and OPT are not unstructured, unregulated channels. They are adjudicated legal processes with multiple layers of government review, specific evidentiary requirements, and denial mechanisms. A government official reviews every single approval in accordance with statutory criteria. Understanding this process and its rigor is foundational to intelligent policy discussion.

H-1B Applicants Face Three Separate Gates, And Two-Thirds Are Rejected Before Review Even Begins

To understand how selective the H-1B process actually is, walk through what an employer must accomplish:

H-1B Registration for the Lottery

Before diving into the full H-1B petition process, there’s a crucial preliminary step for cap-subject petitions: online registration.[6] This electronic system, implemented by USCIS, streamlines the initial selection process.

- Employer creates a myUSCIS account (if they don’t already have one)

- During the registration period, the employer submits an electronic registration for each prospective H-1B worker

- USCIS conducts a lottery to select registrations for further consideration

- Selected registrants are notified and invited to continue the process and file a full H-1B petition.

Labor Condition Application (LCA) with the Department of Labor

Before even filing an H-1B petition with USCIS, an employer must file a Labor Condition Application (Form ETA-9035) with the Department of Labor.[7] This isn’t pro forma. The employer must make specific legal attestations:[7][8]

- The job qualifies as a “specialty occupation”, defined as requiring a bachelor’s degree in a specific field, or equivalent specialized knowledge.

- The employer will pay the higher of: (a) the prevailing wage for that occupation in that geographic area, or (b) the actual wage paid to similarly employed U.S. workers.

- Hiring the H-1B worker will not adversely affect the working conditions and wages of U.S. workers similarly employed.

DOL reviews the LCA for internal consistency and flags obvious problems. The attestation becomes enforceable. If violated, the employer faces substantial penalties, including back wages for U.S. workers, civil fines, and potential visa revocation. More importantly for this discussion: this is where the first substantive gate sits. Weak applications often get challenged or rejected at the LCA stage.[9]

Lottery Selection

Even before USCIS evaluates a single petition, most applications must survive a numerical cap:[9]

- Regular cap: 65,000 visas

- Advanced degree exemption (Master’s degree or higher from a U.S. institution): 20,000 additional visas

- Universities, research institutions, and specific nonprofits: exempt from cap

For fiscal year 2026, USCIS received 358,737 electronic registrations. USCIS conducts preliminary checks to remove duplicates, invalid passports or travel documents, or failed payments. Eligible unique registrations were 336,153, of which 120,141 were selected to apply for approximately 85,000 available cap slots.[9] The selection rate was only 33% of registrants. 30% of the selected did not get an approved slot.

That bears emphasis: two out of three would-be H-1B hires were rejected at the lottery stage, before any petition was even fully prepared. Not because of fraud or abuse, but because demand dramatically exceeds legal supply.

This is the second gate, and it’s incredibly tight.

USCIS Adjudication of Form I-129

Only after surviving the lottery does the complete petition go to USCIS for detailed review. This is where the most rigorous gate sits.

USCIS adjudicators must evaluate two distinct legal questions, each with its own evidentiary burden:[10]

USCIS Officers Demand Detailed Evidence That Jobs Require Specialized Degrees, It’s Not Rubber-Stamping

The occupation must require a bachelor’s degree in a specific field as a minimum entry requirement. USCIS is instructed not to rely solely on generic occupational descriptions (like the Occupational Outlook Handbook). Instead, officers examine detailed documentation: the actual job description, organizational charts, prior hiring practices for similar roles, evidence of past work performed by others in equivalent positions, educational requirements specific to this employer’s industry, and sometimes expert letters from academics or industry practitioners.

The regulation is specific: If a job description shows that the alien is to perform tasks that are not usually performed by a specialty occupation worker, or includes job functions that are not traditionally associated with the claimed specialty occupation, the position is not a specialty occupation.”

This is real scrutiny. It’s the opposite of rubber-stamping.

Does this particular individual actually possess the required qualifications?

Even if the job qualifies, does the candidate have the proper credentials? USCIS examines:

- Educational transcripts and degree certificates

- Work experience documentation

- Whether experience is directly related to the specialty occupation

- Whether the candidate’s background demonstrates the specific knowledge the job requires

An employer cannot simply claim, “We need this person,” and get approval. They must document that this specific person has the particular qualifications for this specific role.

Approval Rates Tell the Story

After all gates, what percentage of H-1B petitions actually get approved?

According to USCIS data for 2026, only 24% of registrants made it through the lottery to the official cap. The denial rates for H-1B petitions (post-lottery) are approximately 2.5–2.8%.[11] That sounds low, but the denominator matters: by the time a petition reaches USCIS for full adjudication, weak applications have often been screened out, withdrawn, or never filed by employers who knew they wouldn’t survive scrutiny.

The more instructive number is the Requests for Evidence (RFE) rate, the percentage of petitions USCIS asks employers to supplement or clarify. This runs between 20–30% for initial H-1B petitions.[12] That means USCIS is actively questioning, scrutinizing, and demanding better documentation on roughly one in four cases.[^10]

That’s not a rubber-stamp approval process. That’s active government oversight.

OPT Requires Full-Time Enrollment, Formal School Approval, and Government Adjudication, Not a Loophole

Optional Practical Training requires students to maintain a valid F-1 status, be enrolled full-time for at least one academic year, get a formal recommendation from their school, and file detailed applications with immigration officials.[13]

For STEM OPT extensions (which allow up to 36 months instead of 12), the requirements tighten further: the job must be directly related to the STEM degree field, the employer must use E-Verify (an automated work authorization system), and the employer must provide a formal training plan detailing how the position develops the student’s knowledge in the STEM field.

Again, this is an adjudicated government process, not an honor system or a free-for-all.

Real Abuse Exists, But It Clusters in Body-Shop Firms, Not the Majority of H-1B Use

This is important: acknowledging that H-1B and OPT are rigorous processes doesn’t mean there’s no abuse. It means abuse is a subset problem, not a systemic one.

Documented abuses cluster in specific segments of the economy:

- Outsourcing and Body-Shopping Firms: Some labor contractors use H-1B explicitly as a cost-arbitrage strategy. They hire foreign workers on H-1B, place them as contractors at client companies, pay them $50,000-$70,000 annually, and bill clients $120,000-$150,000, pocketing substantial margins while undercutting the wages U.S. engineers would command. This is wage theft disguised as visa sponsorship. It’s real, it’s documented, and it deserves enforcement.[14]

- Wage Violations: Some employers attest to prevailing wage requirements but actually pay substantially less, creating a de facto two-tier wage system. Again, real and documented.[14]

- Misclassification: Some employers claim jobs are specialty occupations when they’re not, or claim qualifications the candidate doesn’t possess, betting that adjudicators won’t catch the gap or USCIS will lack resources to vet thoroughly.[14]

- The Economic Policy Institute, a labor-focused research organization, found evidence of widespread wage violations in specific H-1B-heavy sectors and occupations. The evidence is compelling enough to justify enforcement and tighter oversight.[14]

But here’s the critical nuance: Most H-1B approvals are not in these abuse-prone sectors. Roughly half of new H-1B approvals in FY 2024-2025 went to professional, scientific, and technical services roles, not labor contractors and body shops. Universities, which account for a significant share of H-1B use, have strong compliance records and institutional oversight that make wage violations unlikely.

So we have a situation where:

- The dominant use of H-1B aligns with statutory intent (attracting or retaining specialized talent in genuine specialty occupations).

- A meaningful subset of uses, primarily in certain outsourcing and staffing models, reflects systemic misuse.

- The adjudication process itself is rigorous, but enforcement and penalty mechanisms could be tighter.

That’s not “the program is fundamentally broken.” That’s “some abuse occurs in certain sectors and deserves targeted enforcement.”

It’s also not the same as “foreign workers are taking American jobs from the general college graduate population.”

The Senator’s Dilemma, And Why Our Leadership Needs Better Support

Let’s return to that senator and have genuine empathy for the position he’s in.

He represents millions of constituents. Some have lost jobs or struggled with underemployment. Some are recent graduates with expensive degrees and disappointing employment prospects. Some are parents terrified that their children’s college investment won’t pay off. These are real people with real problems, and a good senator feels the weight of that.

He also knows that his job depends partly on being seen as doing something. The public wants action on problems they perceive as urgent. If a senator says, “This is actually a complex systemic issue in higher education that will take 10-15 years to reform,” voters think he’s doing nothing. If he proposes restricting H-1B visas, he’s shown leadership, even if the policy doesn’t solve the underlying problem.

He’s also constrained by what economists and policy experts tell him. If the dominant narrative among economists and immigration analysts is “H-1B and OPT are terrible for American workers,” he feels justified in acting on that narrative. If he’s not an expert in visa programs himself (and few senators are), he’s dependent on advisors, hearing testimony, and prevailing expert consensus.

Here’s where the system breaks down: the expert consensus on H-1B and OPT is genuinely contested, but the political framing treats it as settled.

Some economists argue that H-1B visas depress wages for some American workers, particularly in specific occupations or geographic areas. Other economists argue that the evidence for broad wage depression is weak and that H-1B workers fill skill gaps rather than replace Americans. Some research suggests companies use H-1B to avoid training and developing American talent; other research suggests American universities aren’t producing enough specialists in certain domains, making H-1B a necessity rather than a choice.[15]

A responsible senator faced with contested expert opinion should do several things:

First: Commission deeper analysis. Before proposing a significant policy change, have your staff (or the Congressional Research Service) produce a genuinely comprehensive assessment. What’s the actual scale of harm from H-1B/OPT? Where does it concentrate? What are the counterfactuals? What happens if we eliminate these programs?

Second: Demand root-cause analysis, not symptom-level thinking. Don’t ask, “Are foreign workers hurting American graduates?” Ask “what’s causing 23.8 million college graduates to be unemployed or underemployed, and what role do foreign visa holders play in that?” The first question leads to visa restrictions. The second might lead to very different conclusions.

Third: Consider unintended consequences. America does not have a monopoly on talent, nor does it produce nearly the level of advanced skills it needs to compete. We need to weigh the benefits and costs of every policy. If we eliminate H-1B and OPT:

- What happens to American universities’ ability to attract international students and faculty? (Many come expecting potential pathways to work authorization after graduation.)

- What happens to American companies’ competitiveness in global talent markets?

- What happens to specific sectors (like biotech, quantum computing, and advanced manufacturing) that depend on accessing specialized talent?

- Do the economic benefits to America outweigh the costs, or the opposite?

- Are there better ways to address abuse than abolishing the entire mechanism?

Fourth: Push back against ideological constraints. For senators predisposed to oppose immigration, resisting H-1B restrictions is uncomfortable. For senators predisposed to support immigration, acknowledging program abuses is uncomfortable. But serious solutions require confronting discomfort. It requires being willing to say things your political base doesn’t want to hear.

The senator we’re discussing would be doing the American public a service if he said something like this:

“I’m genuinely concerned about American college graduates struggling to find work. But the evidence suggests the problem is primarily structural; we’re producing far more graduates in low-demand fields than the labor market needs, while simultaneously failing to steer enough students into high-demand fields. Foreign workers on H-1B and OPT account for roughly 1 million jobs in an economy of 160 million workers, and evidence suggests they’re concentrated in roles that complement rather than directly replace American workers. There are abuses in the visa programs, particularly in certain outsourcing sectors, and those need enforcement. But abolishing the programs wholesale would hurt America’s long-term competitiveness without solving the real problem: a higher-education system with broken incentives. Let me propose a comprehensive approach that addresses both visa program abuses and the structural education and employment issues affecting 25 million Americans.”

That’s harder politically. It requires resisting easy answers. It means defending the value of necessary foreign workers while still taking American concerns seriously. It requires admitting the problem is partly domestic and partly requires long-term structural reform, not just legislative action.

But that’s what serious policy leadership looks like.

Visa Workers Account for 1 Million Jobs, The Crisis Affects 25 Million Graduates

Before any other analysis, we need to establish a baseline scale. Because scale determines everything about how seriously we should take a policy lever.

Nearly 25 Million College Graduates Face Unemployment or Underemployment

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey for September 2025, the United States has 163.65 million employed workers.[16] Of these, 67.51 million hold bachelor’s degrees or higher.[17]

Of that 67.51 million:

- 1.92 million are actively unemployed and searching for work.[17]

- 22.75 million are underemployed, working in jobs that don’t require a college degree.[18]

Combined, 24.67 million college graduates are facing employment challenges.

Think about that number. Nearly 25 million people invested years and often tens of thousands of dollars in degrees, only to find themselves unable to use them. That’s the population affected that we need to help.

Even Eliminating Every Visa Worker Would Address Only 4% of Affected Graduates

H-1B and OPT programs together account for approximately 1.024 million foreign workers in the U.S. labor market:[^18][^19]

- H-1B: ~730,000 workers[19]

- OPT: ~294,000 workers[20]

Now do the math:

1 million foreign workers: 25 million struggling American graduates = 1 to 25

Even if you could eliminate every single visa position tomorrow and perfectly replace each one with an American graduate (economically impossible, as we’ll see), you’d address only 4.1% of affected graduates.

Where do the other 23.65 million go?

This is not rhetorical. This is the fundamental policy question Washington should be pursuing.

Even Narrowing to STEM Fields, Visa Workers Explain Only 12% of Graduate Struggles

The strongest counterargument to the scale analysis is: “H-1B and OPT aren’t evenly distributed. They concentrate in STEM fields where the domestic supply is tightest. Maybe the impact is bigger there?”

It’s a fair point. Let’s test it.

STEM Workforce: According to NSF data, approximately 17.55 million American workers with bachelor’s degrees or higher work in STEM fields. Out of a total U.S. workforce of 163.65 million employed, that’s about 10.7%.[21]

STEM Unemployment/Underemployment: Recent STEM graduates (ages 22-27) unemployment varies dramatically:[3]

- Physics: 7.8% unemployment

- Computer Science: 6.1% unemployment

- Mathematics: 3.8% unemployment

- Civil Engineering: 1.0% unemployment

Averaging STEM fields, recent graduate unemployment is roughly 3.8%, compared to 4.8% for all recent college graduates. STEM graduates also face underemployment, working in roles that don’t require a degree, though at lower rates than non-STEM graduates (approximately 28.9% for technical fields vs. 41.4% overall recent graduates).[22]

Rough estimation of total STEM graduates affected:

- Recent STEM graduate unemployment: ~667,000 (3.8% of 17.55M)[22]

- STEM graduate underemployment (28.9% of 17.55 million): ~5.07 million[22]

- Total affected STEM graduates: ~5.74 million

STEM Visa Concentration: H-1B and OPT workers are heavily concentrated in STEM:

- H-1B in STEM fields: ~511,000 (~70% of total H-1B)[23]

- OPT in STEM fields: ~176,000 (60% of total OPT)[24]

- Combined in STEM: ~687,000

Now the STEM-only ratio:

687,000 visa workers in STEM to 5.74 million affected STEM graduates = 1 to 8.4

Even narrowing to STEM, visa workers represent only 12.0% of the affected population. Seven out of eight affected STEM graduates face employment challenges unrelated to visa competition.

If OPT STEM Visas are keeping Americans from STEM jobs, then eliminating them addresses 3% of America’s STEM unemployment and Underemployment! Why does anyone think this is the source of our problem?

But here’s where it gets fascinating.

Even when we examine categories where H-1B and OPT could be crowding out domestic workers, we don’t see elevated unemployment rates to support that argument.

The CS Paradox: 3.55x More Visa Workers Than Affected Graduates, Yet Only 6.1% Unemployment

Zoom in further to just computer science and IT, the epicenter of the visa debate:

CS Recent Graduates Affected:

- Unemployed (at 6.1% unemployment rate): ~42,000[3]

- Underemployed (at 16.5% underemployment rate): ~115,000[3]

- Total: ~157,000

Visa Workers in IT/CS:

- H-1B in computer occupations: ~467,000 (63.9% of all H-1B)[25]

- OPT in computer science: ~91,000 (31% of all OPT)[26]

- Combined in IT/CS: ~558,000

There are 3.55 times more visa workers in IT/CS than there are affected recent American CS graduates combined.

This creates a genuine paradox: if visa workers so dramatically outnumber the affected CS graduate population and are indeed crowding out Americans, why do CS graduates have only 6.1% unemployment? It’s not even the peak of STEM categories.

The answer to this paradox reveals what’s actually happening. And it has almost nothing to do with visa competition.

Domestic Oversupply and AI Automation, Not Visa Competition, Explain CS Graduate Unemployment

The computer science paradox, that visa workers vastly outnumber affected graduates, yet unemployment remains around normal for STEM, points to structural problems that no visa policy can address.

CS Degree Production Exploded 238% Since 2001 While H-1B Numbers Stayed Flat

Computer science degree production has exploded over the past 20 years. In 2001-02, the USA conferred 68,290 Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctor’s degrees. BY 2021-22 that number grew to 162,631. [21]

Between 2001 and 2021, CS degree production increased by 238%.

Universities, seeing student demand and tuition revenue, expanded CS programs dramatically. Every school, from elite research universities to regional colleges, now offers computer science degrees, regardless of whether they have the faculty expertise, industry connections, or placement success to justify the investment.

The result is a degree production machine far exceeding market absorption capacity.

Berkeley computer science professor Hany Farid documented this transformation directly. “Our students typically had five internship offers throughout their first four years of college. They would graduate with exceedingly high salaries, multiple offers. They had the run of the place. That is not happening today. They’re happy to get one job offer.”[27]

This shift from scarcity to surplus occurred despite H-1B and OPT numbers remaining relatively stable since 2015. The dramatic employment deterioration for CS graduates wasn’t driven by visa policy; it was driven by domestic degree production, flooding the market with more graduates than available positions.

Think about the economics. If there were 50,000 entry-level CS positions annually and America were producing 50,000 CS graduates while importing 10,000 via OPT, visa competition would explain unemployment. But if there are 50,000 positions and America is producing 180,000+ CS graduates domestically while 10,000 arrive via OPT, the visa workers aren’t the constraint, domestic oversupply is.

AI Tools Are Eliminating Entry-Level Developer Roles That New Graduates Traditionally Filled

The specific jobs entry-level CS graduates traditionally filled are precisely the roles most vulnerable to AI automation.

GitHub Copilot writes basic code. ChatGPT debugs programs. Claude handles API documentation. Companies that previously needed 10 junior developers to build features now need two mid-level developers armed with AI tools.

Bureau of Labor Statistics projections show 10.1% growth in computer and mathematical occupations through 2034, but this growth is concentrated in specialized roles, such as AI/ML engineers and cybersecurity specialists, rather than entry-level positions.[28]

Andrew Ng, the former Google Brain scientist and Stanford professor, recently broke down what he’s observing in the talent markets. And his insights reveal a crucial aspect of how AI is reshaping hiring.[29]

Ng describes a clear hierarchy of engineering talent in the AI era:

The Bottom Tier: Computer science graduates who never learned AI or modern productivity tools. These are people entering the job market without exposure to cloud computing, AI tools, or how to leverage productivity technologies.

Ng is blunt: “I just don’t hire people like that anymore. Those people may get into trouble at some point.” He points out that universities are graduating cohorts of computer science students who have never heard of cloud computing, essentially graduates without the foundational tools of modern work.

This happened while H-1B and OPT numbers stayed relatively constant. The entry-level jobs aren’t going to foreign workers; they’re disappearing entirely.

H-1B Workers Earn $125K Median, 64% More Than New Grad Starting Salaries of $76K

Here’s a critical point that gets lost in political rhetoric: H-1B visa workers typically don’t compete for entry-level positions.

The median H-1B salary in computer occupations is approximately $125,000.[30]

The BLS says the median wage of all US workers in Computer and Mathematics is $105,850.[31] Median H-1B is 18% higher.

The overall projection for the Class of 2025 Bachelor’s in Computer Science graduates is $76,251.[32] That’s a 64% gap, not a slight difference.

Why? H-1B workers fill specific, specialized roles, project-based work, and mid- to senior-level positions. Many require 3-5 years of experience, which recent graduates don’t have.

The economics reveal this clearly: Companies don’t sponsor expensive H-1B visas, with legal costs, paperwork, uncertainty, and timing delays, if they could hire fresh American graduates more cheaply and easily. The economics only make sense if the visa worker fills a genuinely different market need.

Companies sponsor H-1B visas when they genuinely can’t find domestic workers with specific expertise, when they’re retaining someone who proved valuable during OPT, when they need specialists in emerging technologies, or when they’re competing internationally for talent.

This market segmentation is crucial because it means H-1B workers are not directly competing for the entry-level positions where recent graduates face unemployment.

The Senator’s Key Evidence Rests on 75 Survey Responses, With a 1.7% to 13.9% Confidence Interval

Remember that senator’s physics statistic? This example perfectly shows how emotion overrides data in policy thinking.

The New York Fed figure showing physics graduates with 7.8% unemployment, the second-highest of all majors, comes from the American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS is massive and valuable, but it uses a 1% sampling rate across the entire U.S. population.[33]

For large populations, 1% sampling provides excellent statistical reliability. For tiny subgroups like physics majors, it creates severe problems.

Physics Degrees Are 0.37% of All Bachelors—Too Small for Reliable ACS Sampling

Physics awards approximately 7,500 bachelor’s degrees annually. Out of 2 million bachelor’s degrees awarded in the U.S., that’s just 0.37%. [34]

With ACS’s 1% sampling rate, the expected number of recent physics graduates in the survey is approximately 75 individuals per year across a rolling 5-year window.[^25][^26]

With a sample size of 75 and a measured unemployment rate of 7.8%, the 95% confidence interval ranges from roughly 1.7% to 13.9%.

That’s not a small margin of error. That’s a canyon.

Year-to-year fluctuations of 1–2 percentage points are entirely consistent with sampling variance alone, meaning they tell us nothing about actual labor market changes.

A senator making major policy based on this statistic is making policy based on data that could easily be sampling noise rather than a real phenomenon.

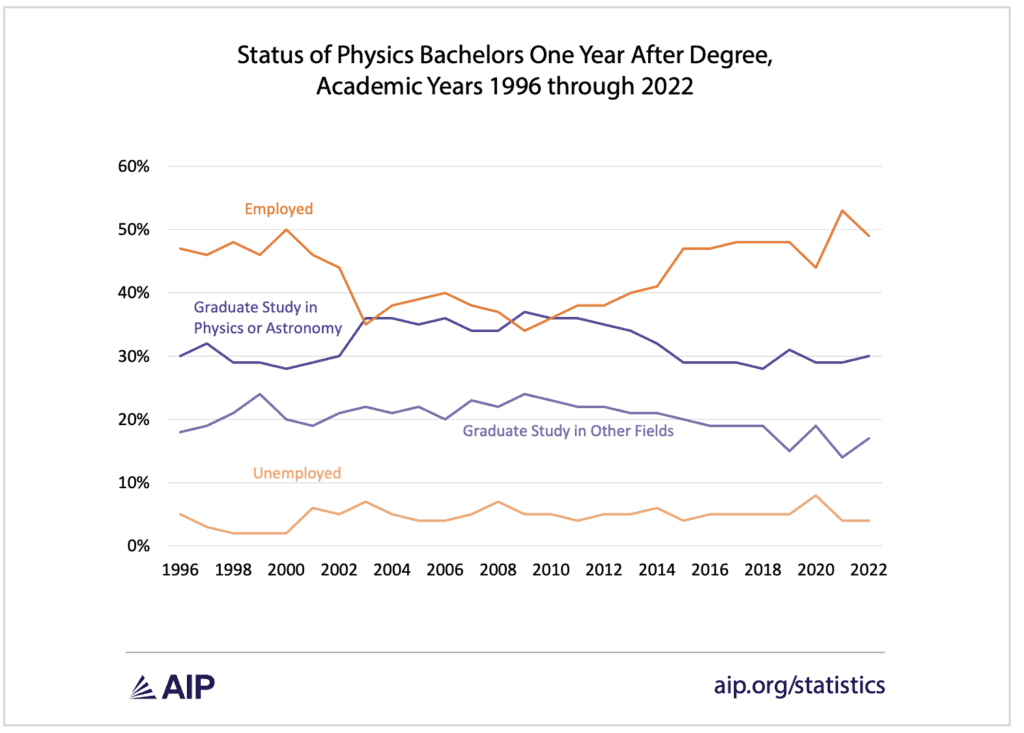

Higher-Quality AIP Data Shows Physics Unemployment Stable at 4-6% for 25 Years, Regardless of Visa Policy

The American Institute of Physics (AIP) conducts surveys with much higher response rates and sample sizes, approximately 2,000–3,000 physics degree holders annually. Their historical data covering 1996 through 2020 shows physics bachelor’s unemployment consistently hovering around 4–6%.[35]

Most critically, this shows remarkable stability over 25 years, through the dot-com boom and bust, the post-9/11 recession, the 2008 financial crisis, multiple H-1B policy changes, OPT extensions, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

If H-1B and OPT were primary drivers of physics unemployment, this pattern should show clear spikes when visa policies expanded. It doesn’t. Unemployment wobbles between 4-6% regardless of visa policy changes.

That’s not the signature of foreign worker competition. That’s the signature of structural characteristics specific to physics labor markets.

Physics Unemployment Reflects Field-Specific Dynamics, 50% Pursue Grad School, Many Choose Non-Physics Careers

Physics has unique labor market characteristics that explain persistently elevated unemployment:

Graduate School Self-Selection: Approximately 50% of physics bachelors immediately pursue graduate degrees. This self-selects the strongest academic performers into PhD programs, leaving a less competitive pool in the immediate job market. Physics PhD programs take 5–7 years, creating cyclical effects where simultaneous gluts and shortages occur depending on timing.[35]

Field Leakage: Physics bachelor’s degree holders who go on to employment rather than continue to graduate school are not predominantly entering careers in physics. They choose a variety of careers, including finance (quantitative analysis), software engineering, data science, teaching, policy, and business.[35]

When the BLS classifies a physics graduate working as “underemployed,” that’s technically accurate by their methodology. But it’s misleading; many represent deliberate career choices leveraging physics training, not labor market failures.

Small Absolute Numbers Mean Minimal Policy Impact: Even if you eliminated 100% of physics unemployment through visa restrictions (impossible given structural factors), you’d affect approximately 300 people annually, 0.001% of the 25 million college graduates affected nationwide.

Using physics unemployment to justify broad visa restrictions is policy analysis by anecdote. It’s like diagnosing a heart attack based on a hangnail. The symptom is visible, but it’s fundamentally unrelated to the actual patient’s condition.

And it exemplifies a broader problem: **the loudest voices in policy are rarely well-informed enough to understand root causes, and when we rush to adopt solutions that address symptoms, we end up breaking other, far more important goals. ****

China Graduates 4.5x More STEM Students Annually, Visa Programs Are How America Retains Competitive Advantage

Here’s what the visa debate almost entirely overlooks: the strategic context in which these programs operate.

The U.S. is in an intensifying, long-term competition with China and other nations for advanced talent in critical fields.

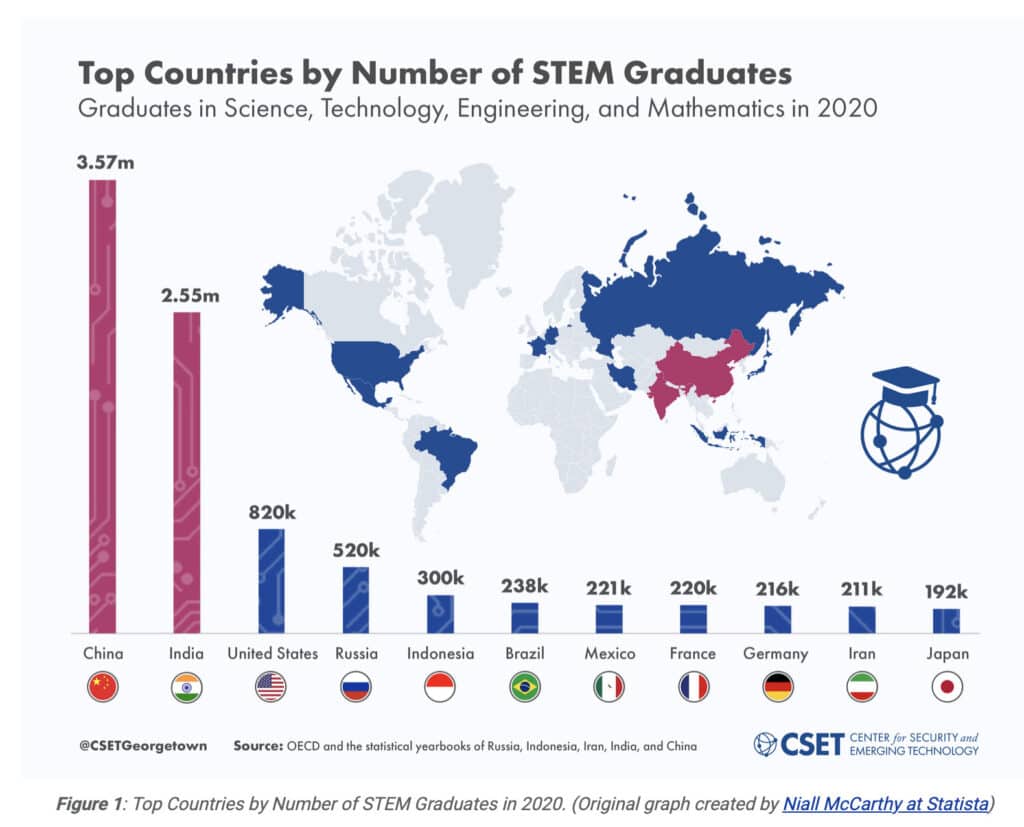

China Produces 3.6 Million STEM Grads Annually; America Produces 820,000

China now graduates approximately 3.6 million STEM students annually. India graduates approximately 2.6 million. The United States graduates approximately 820,000.[36]

China produces 4.5 times more STEM graduates than America every single year.

Quality matters; American universities remain globally prestigious; our research infrastructure is unmatched; and, on a per-capita basis, adjusting for population, we’re more productive than China.[37] But when you’re competing in quantum computing, artificial intelligence, hypersonics, biotechnology, and other domains where national security depends on technical leadership, sheer numbers start to matter enormously.

America’s Competitive Edge Is Attracting and Retaining World-Class Talent

The single biggest advantage America has maintained in this competition is our ability to attract and retain world-class scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs from around the globe.[37] Please read: America’s Talent Crisis: The War America Is Losing (And Doesn’t Even Know It’s Fighting)

The best students from China, India, Europe, Latin America, and Africa want to study in American universities. Many want to stay and contribute to American innovation. H-1B and OPT programs are mechanisms for converting that educational advantage into a sustained competitive advantage by keeping talented people here after we’ve trained them.[37]

When we treat H-1B and OPT primarily as political punching bags rather than strategic talent-retention tools, we risk undermining one of the few clear advantages America still holds over competitors with vastly larger populations.

Restricting Visas Sends American-Trained Talent Back to China, India, and Europe, With Their Skills

When we make it harder for international students to work in America after graduation or create a hostile atmosphere suggesting they’re unwelcome, they return home. And they take their American training with them.

That physics PhD who studied quantum computing at MIT? If they can’t work in America, they work in Shanghai, advancing Chinese quantum capabilities.

That computer science graduate who trained in AI/ML at Carnegie Mellon? If they face hostile rhetoric about “stealing American jobs,” they return to Seoul or Singapore, building their countries’ AI sectors.

The notion that restricting these visas “protects American jobs” ignores reality: these programs are how America maintains technological leadership against vastly larger competitors determined to overtake us.[37]

It’s the policy equivalent of poisoning our own well to keep others from drinking from it.

America Faces Critical STEM Shortages While 25 Million Graduates Struggle, Because We Train for the Wrong Fields

Here’s the brutal irony that exposes the incomplete framing of the visa debate:

The National Science Board of NSF says, “The United States is facing an accelerating STEM talent crisis that increasingly puts our economic and national security at risk.” [38]

While we have 25 million college graduates struggling with unemployment or underemployment, we simultaneously face critical skills shortages in areas essential to national security and economic competitiveness.

These aren’t jobs that visa workers are stealing.” These jobs are going unfilled because we don’t have enough Americans with the proper training, and we’re not training enough Americans for these fields.

Why?

Because of the exact structural dysfunction we’ve been discussing. We are producing significant numbers of degrees in low-demand skills.

The result is a terrible misallocation of human capital:

- Millions of college-educated Americans are struggling to find appropriate employment

- Hundreds of thousands of critical jobs are going unfilled

- America is systematically losing competitive ground in fields essential to national security and economic leadership

This is not a problem that visa restrictions solve. This requires fixing how we guide students into fields of study.

And yet, political energy goes into restricting the number of needed foreign workers rather than reforming higher education incentives.

Restricting Visas Sacrifices Talent Retention and Competitive Advantage, For 4% of the Problem

When we look at the whole landscape, the structural dysfunction in higher education producing 25 million underemployed/unemployed graduates, the critical unfilled positions in national security-critical fields, and the competition for talent from China and India, restricting H-1B and OPT visas, represents a specific strategic choice with foreseeable consequences.

Eliminating Visa Programs Would Leave Critical Jobs Unfilled and American Innovation Offshored

Domestic Consequences:

- Fewer International students come to American universities (that’s a genuine advantage we lose – their full cost fees or exceptional talent).

- Many of the top ones, after graduating with American training, return home rather than face visa restrictions.

- This reduces the efficiency of our educational investment; we’ve trained them, but don’t retain their talent.

- Over time, international enrollment declines as students realize they can’t stay post-graduation; American universities lose revenue and prestige.

Competitive Consequences:

- American companies lose flexibility to bring in or retain specialized talent for a competitive advantage.

- Critical positions in AI, quantum, advanced manufacturing, and cybersecurity remain unfilled.

- American innovation slows in fields where we compete directly with China and other nations.

- American companies increasingly offshore their R&D and strategic functions because they can’t access talent domestically.

Employment Consequences for American Graduates:

- The 25 million underemployed/unemployed college graduates are not hired en masse to fill the cybersecurity, AI/ML, and advanced manufacturing roles.

- Why? Because they don’t have the proper training, and restricting visa workers doesn’t create that training retroactively.

- The jobs remain unfilled or go offshore.

- The college employment crisis continues unchecked because the actual problem, structural dysfunction in higher education, remains unfixed.

55% of Billion-Dollar Startups and 65% of Top AI Companies Have Immigrant Founders

Here are some facts worth considering:

- 55% of America’s startup companies valued at $1 billion or more have at least one immigrant founder.[11]

- Immigrants have founded or cofounded nearly two-thirds (65% or 28 of 43) of the top AI companies in the United States.[11]

- 70% of full-time graduate students in fields related to artificial intelligence are international students.[11]

- Get rid of these visas and run the risk of missing the next Elon Musk, Jensen Huang, Satya Nadella, or Sundar Pichai. There are many more…

By focusing political capital on visa restrictions rather than structural higher-ed reform, we sacrifice:

- Talent retention: The ability to keep exceptional international talent in America after we’ve educated them.

- Competitive advantage in critical fields: The flexibility to bring in or retain specialists when domestic supply is insufficient.

- University prestige and revenue: International students and faculty are crucial to top-tier institutions’ research and educational missions.

- Innovation in emerging fields: Where first-mover advantage matters (AI, quantum, biotech), restricted talent access directly impacts innovation speed and quality.

All in exchange for addressing approximately 4.1% of the college employment crisis.

Solving the Crisis Requires Visa Program Fixes, Not Elimination, Plus Comprehensive Higher-Ed Reform

If the goal is genuinely to improve outcomes for American college graduates while maintaining America’s competitive position in global talent competition, the policy approach should be:

Target Documented Abuse Through Wage-Based Selection and Enforcement, Keep Talent Retention Mechanisms

Target documented abuses without eliminating talent retention mechanisms: shift H-1B allocation from lottery to wage-based selection, prioritizing higher salaries; strengthen prevailing wage enforcement with meaningful penalties; increase Department of Labor auditing resources; restrict body-shop and staffing-firm usage operating primarily for cost arbitrage; and fast-track advanced degree holders from U.S. institutions in critical shortage fields.

For OPT: maintain STEM extensions with tighter direct-employment oversight, require training plans demonstrating actual skill development, tighten restrictions on staffing firms, and expand for critical shortage fields.

These reforms address real abuse without eliminating talent retention.

Require Outcome Transparency, Gainful Employment Standards, and Strategic Workforce Development

Remember psychology? If the BLS projects 12k jobs over the next 10 years, with 130k bachelor’s degrees and 40k graduate degrees produced each year, a significant number of those graduates will end up underemployed. They will have given up four or more years of earnings, paid out-of-pocket costs to attend college, and graduate with a degree that is not necessary for the job they end up filling. That job may often start with lower salaries than a peer who graduated from high school and went off to work.

This crisis is not isolated. It’s the challenge causing the lion’s share of our problem.

Fixing this is harder politically, but infinitely more important:

Transparency on Outcomes: Mandate that universities publish detailed employment-outcome data by major, including underemployment rates, earnings distributions, debt-service ratios, and net present value calculations. Make poor outcomes visible and create reputational pressure.

Gainful Employment Standards: Require programs to demonstrate that graduates earn enough to repay student debt in a reasonable time. Programs consistently failing this test lose access to federal student aid, creating institutional incentive to (a) control costs, (b) improve placement, and (c) limit enrollment in oversupplied fields.

Strategic Workforce Development: Subsidize education in critical shortage fields, cybersecurity, AI/ML, advanced manufacturing, biotech, quantum, and semiconductor engineering. Provide free or heavily subsidized tuition, accelerated loan forgiveness, and employer tax credits for hiring graduates in these fields.

No Major Policy Vote Without Comprehensive Analysis of Scale, Root Causes, and Unintended Consequences

Here’s where I’m most sympathetic but also most demanding of our senators:

Require comprehensive analysis before major policy votes: Before supporting visa restrictions, demand staff produce a detailed analysis of the actual impact scale (not anecdotes), a root-cause analysis of the problem being solved, an analysis of unintended consequences, a comparison of different policy levers and their impacts, and evidence for proposed solution effectiveness.

Create incentive for honest discussion: Build political space where senators can acknowledge complexity without losing credibility. “This is more complicated than initially thought” shouldn’t be a political weakness.

Demand iterative evaluation: Major policy changes should include mechanisms for evaluation. If we restrict H-1B visas and graduate unemployment doesn’t improve, we should reverse course without losing face.

Restricting Visas Won’t Solve the College Employment Crisis; It Requires Harder Work: Higher-Ed Reform

Restricting H-1B and OPT visas will not solve the college employment crisis.

If we restrict them to zero, the 25 million underemployed graduates won’t automatically get hired for positions currently filled by visa workers. Why? Most visa workers and college graduates occupy different market segments—visa workers do specialized technical roles; recent graduates seek entry-level work.

Critical positions in emerging fields will remain unfilled or go offshore. The real problem—structural dysfunction producing graduates in oversupplied fields—remains unchanged.

Visa reforms can address abuses and improve program integrity. But they’re not solutions to the main crisis. That requires harder work: higher-education reform, better workforce planning, and skills-based assessment.

Smart Leaders Deserve Better Analytical Support—And Political Space to Change Their Minds

That senator I mentioned at the beginning? He’s not a villain. He’s an intelligent person trying to address a real problem: millions of Americans struggling with college employment outcomes. His instinct to “do something” is correct.

His error wasn’t in caring; it was in analyzing too quickly, letting visible politics override rigorous root-cause thinking, and focusing on a symptom (visa workers) that explains only a tiny fraction of the actual problem.

This is an American tendency: we’re drawn to visible, concrete scapegoats. They’re easier to address than diffuse structural dysfunction. They generate political credit for “taking action.”

But when we make major policy decisions based on incomplete analysis, we end up solving the wrong problems while breaking other vital things.

The college employment crisis is real and urgent. So is America’s need to maintain a competitive advantage in talent competition against rivals with far larger populations. These aren’t necessarily in conflict, but they are if we waste political capital and policy creativity on the wrong levers.

Our leaders deserve better analytical support. They should have research staff and expert advisors saying: “Yes, this is a real problem. No, visa programs aren’t the root cause. Here’s what the data actually shows. Here’s what would actually solve this. Here are the unintended consequences if we go down that path instead.”

And they should have cover to say publicly: “I care deeply about this problem, but the solution isn’t what I initially thought. Here’s what the data shows we should do.”

That’s not a weakness. That’s integrity. It’s also what good governance requires.

The question is whether our political system—with its pressure for visible action, ideological constraints, and limited analytical infrastructure—can support that kind of thinking.

The stakes are high enough that we have to try.

This Isn’t Just Policy; Every Organization Faces the Same Wrong-Problem Risk Without Dissent Culture

This essay has been mostly about policy and politicians. But if you think your CEO, VP, or manager is exempt from wrong framing and going down rabbit holes, you are likely ignoring reality.

At McKinsey and Company, we had an obligation to dissent. That means that everyone had to assist in redirecting the conversation to the facts and what was important. That simple cultural expectation reduced framing error. Still, it occurred frequently.

When leadership is hierarchical, without room for diverse points of view and opportunities for dissent, you will find significant opportunities for misframing and the resultant misallocation of focus and resources!

Reference Sources

- McKinsey & Company. “Bias busters: When the question, not the answer, is the mistake.” Strategy & Corporate Finance, September 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/bias-busters-when-the-question-not-the-answer-is-the-mistake

- Schmitt, Eric (@Eric_Schmitt). “The Optional Practical Training program is a cheap foreign-labor program…” and related posts on immigration policy. X (formerly Twitter), October 2025. https://x.com/Eric_Schmitt/status/1989741493595308461 and https://x.com/Eric_Schmitt/status/1993035234812838338 and https://x.com/Eric_Schmitt/status/1989741410137108558

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates.” Interactive data tool showing unemployment rates by major. Accessed November 2025. https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market

- U.S. Senate. “About Senator Eric Schmitt.” Official biography and committee assignments. Accessed November 2025. https://www.schmitt.senate.gov/about/

- Shivamber, Leon. “Warning: This Degree Could Be Hazardous To Your Wealth!” Analysis of the college wealth premium. Shivamber.com, September 3, 2025. https://shivamber.com/warning-this-degree-could-be-hazardous-to-your-wealth/

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “H-1B Electronic Registration Process.” Overview of the registration requirement for cap-subject petitions. Accessed November 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations/h-1b-electronic-registration-process

- U.S. Department of Labor. “Form ETA-9035: Labor Condition Application for H-1B Filings.” LCA requirements and attestations. Accessed November 2025. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/foreign-labor/programs/h-1b and https://flag.dol.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/ETA_Form_9035.pdf

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “H-1B Specialty Occupations.” Defines specialty occupation requirements and adjudication standards. Accessed November 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/h-1b-specialty-occupations

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “H-1B Electronic Registration Process.” Overview of the registration requirement for cap-subject petitions. Accessed November 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations/h-1b-electronic-registration-process

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Adjudication of Form I-129, Petition for Nonimmigrant Worker.” USCIS Adjudicator’s Field Manual. Accessed November 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/policy-manual-afm/afm31-external.pdf

- National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP). “H-1B Petitions and Denial Rates for FY 2025.” Policy brief on H-1B adjudication trends. November 2025. https://nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/H-1B-Petitions-and-Denial-Rates-For-FY-2025.NFAP-Policy-Brief.2025.pdf

- DavidsonMorris. “H-1B Visa Data.” Overview of cap usage and processing trends. Accessed November 2025. https://www.davidsonmorris.com/h1b-data/

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “OPT Process at a Glance” and “Optional Practical Training (OPT) for F-1 Students.” SEVIS Help Hub and USCIS guidelines. Accessed November 2025. https://studyinthestates.dhs.gov/sevis-help-hub/student-records/fm-student-employment/f-1-optional-practical-training-opt and https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/students-and-exchange-visitors/optional-practical-training-opt-for-f-1-students#:~:text=Pre%2Dcompletion%20OPT:%20You%20may,per%20week)%20or%20full%20time.

- Costa, Daniel and Hira, Ron. “New Evidence of Widespread Wage Theft in the H-1B Program.” Economic Policy Institute, December 2021. https://www.epi.org/publication/new-evidence-widespread-wage-theft-in-the-h-1b-program/

- National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). “Working Papers on H-1B and Labor Market Wage Effects.” Compilation of research by Bound et al. (2017), Mayda et al. (2017), and Hunt & Gauthier-Loiselle (2008). Accessed November 2025. John Bound, Gaurav Khanna, and Nicolas Morales, “Understanding the Economic Impact of the H-1B Program on the U.S.,” NBER Working Paper 23153 (2017), https://doi.org/10.3386/w23153. and Anna Maria Mayda, Francesc Ortega, Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber, “The Effect of the H-1B Quota on Employment and Selection of Foreign-Born Labor,” NBER Working Paper 23902 (2017), https://doi.org/10.3386/w23902 and Jennifer Hunt and Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle, “How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation?,” NBER Working Paper 14312 (2008), https://doi.org/10.3386/w14312.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “The Employment Situation.” Monthly economic news release, September 2025. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table A-4. Employment status of the civilian population 25 years and over by educational attainment.” Current Population Survey, September 2025. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t04.htm

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates: Underemployment Rates.” Data showing 33.7% underemployment as of June 2025. https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market#–:explore:underemployment

- FWD.us. “H-1B Visa Program.” Policy brief on legal immigration and workforce needs. Accessed November 2025. https://www.fwd.us/news/h1b-visa-program/

- Institute of International Education (IIE). “Open Doors 2025 International Student Census Tables.” Annual data on international student enrollment. November 2025. https://opendoorsdata.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/OD25_Intl-Student-Census_Tables.xlsx

- National Science Foundation. “The STEM Labor Force: Scientists, Engineers, and Skilled Technical Workers (NSB-2024-5).” Science and Engineering Indicators 2024. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20245/ Table SLBR-23 and https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_325.35.asp

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates.” Unemployment rates by major derived from NCES and ACS data (2023). Accessed November 2025. https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market Weights were derived from NCES bachelor’s degree data (2021-22), which reports approximately 435,000 total STEM degrees annually. Individual major breakdowns were estimated using NCES aggregate categories and subfield data from ASEE and College Factual. The NY Fed unemployment and underemployment rates are based on 2023 American Community Survey data for early-career graduates ages 22-27

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers: Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report to Congress.” October 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/reports/ola_signed_h1b_characteristics_congressional_report_FY24.pdf

- Anderson, Stuart. “New Immigration Rule Will End Or Restrict Student Practical Training.” Forbes, November 11, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/stuartanderson/2025/11/11/new-immigration-rule-will-end-or-restrict-student-practical-training/

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers: Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report to Congress.” October 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/reports/ola_signed_h1b_characteristics_congressional_report_FY24.pdf

- NAFSA: Association of International Educators. “CRS Focus Report: Optional Practical Training (OPT) for Foreign Students.” Regulatory information brief. Accessed November 2025. https://www.nafsa.org/regulatory-information/crs-focus-report-optional-practical-training-opt-foreign-students-united

- Mokhtari, Zahra. “Leading computer science professor says ‘everybody’ is struggling to get jobs: ‘Something is happening in the industry’.” Business Insider, September 2025. https://www.businessinsider.com/computer-science-students-job-search-ai-hany-farid-2025-9

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment Projections: 2024-2034.” News release on occupational growth and AI automation. August 2025. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.nr0.htm

- Hughes, Jordan. “Andrew Ng lays out a hierarchy of engineering talent — including who’s in trouble and who he refuses to hire.” Business Insider, November 2025. https://www.businessinsider.com/andrew-ng-talent-engineer-ai-hire-college-graduates-computer-science-2025-11

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers: Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Report to Congress.” October 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/reports/ola_signed_h1b_characteristics_congressional_report_FY24.pdf

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Occupational Projections and Characteristics.” Employment Projections program data. Accessed November 2025. https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/occupational-projections-and-characteristics.htm

- National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). “Salary Survey, 2024-2025.” Projections for Class of 2025 bachelor’s graduates. Accessed November 2025. https://www.naceweb.org/about-us/press/engineering-computer-sciences-top-salary-projections-for-class-of-2025-bachelors-grads

- U.S. Census Bureau. “American Community Survey: Sample Size and Data Quality.” Methodology and variance documentation. Accessed November 2025. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/methodology/sample-size-and-data-quality/ and https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/Search?query=bachelors%20degree%20conferred&query2=bachelors%20degree%20conferred&resultType=all&page=1&sortBy=relevance&overlayDigestTableId=202328

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). “IPEDS Data: Physics Bachelor’s Degrees.” Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. Accessed November 2025. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/Search

- American Institute of Physics (AIP). “Physics Bachelors Initial Employment.” Statistical Research Center data (1996-2020). Accessed November 2025. https://aip.brightspotcdn.com/f6/e4/2a07108a4456aad9e6483afb26eb/0037-employment-booklet-2021and2022-bach-i1.pdf

- Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). “The Global Distribution of STEM Graduates: Which Countries Lead the Way?” Georgetown University, Accessed November 2025. https://cset.georgetown.edu/article/the-global-distribution-of-stem-graduates-which-countries-lead-the-way/

- Shivamber, Leon. “America’s Talent Crisis: The War America Is Losing (And Doesn’t Even Know It’s Fighting).” Shivamber.com, November 4, 2025. https://shivamber.com/americas-talent-crisis-the-war-america-is-losing-and-doesnt-even-know-its-fighting/

- National Science Board. “The Talent Treasure.” National Science Foundation, 2024. https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/files/nsb-talent-treasure-2024.pdf

- Various Organizations. “Policy Proposals for H-1B Reform.” Summary of legislative and regulatory proposals from NFAP, AILA, and other stakeholders. 2025.