A good leader takes a little more than his share of the blame, a little less than his share of the credit.

Arnold H. Glasow

Leadership and decision-making lessons based on examining the discussion we should have had about Afghanistan.

TLDR: The ongoing exit from Afghanistan presents many lessons for leaders about how we make decisions, the importance of dissent, the facts we use, the alternatives we explore, and the thought we put into implementation. My hope in writing this was twofold:

- To illustrate the gap between political thought and reality, and

- To draw out some lessons that each of you decision-makers or decision supporters can reflect on.

Like many of you, I watch the daily challenges faced as we exit Afghanistan with great concern.

The Situation

For the first time in President Biden’s term, we find the Democrat embracing a policy or strategy started under the Trump presidency. The premise is that America has spent too much treasure in Afghanistan, money and lives, and the mission accomplished.

President Biden described the costs in an interview on 8/2/2021: (SIC) “Look, I had a basic decision to make. I either withdraw America from a 20-year war that, depending on who’s analysis you accept, cost us $150 million a day for 20 years or $300 million a day for 20 years. And you know I carry this card with me every day. And who, in fact, where we lost 2,448 Americans dead and 20,722 wounded. I either increase the number of forces we keep there and keep that going or I end the war. And I decided to end the war.“

Both Presidents describe that mission as the capture or death of Bin Laden and eliminating Al Quaeda’s capability to inflict harm on U.S. soil.

Both articulated the view that Afghanistan no longer represents a national security interest.

Both had strategies to withdraw from Afghanistan.

Trump had previously set a target of May 1, 2021, which he now describes as a conditional plan and argues he would not have executed under current circumstances. We will never know if such a strategy was viable.

We know that President Biden embraced an exit and set his administration’s plan to accomplish this withdrawal from Afghanistan by 9/11/2021. That date is crucial as it represents the 20th anniversary of the event that triggered U.S. forces to enter Afghanistan in the first place.

Implementing President Bidens’ plan has led us to the point we are today, with thousands of Americans, allies, and Afghans in danger and surrounded by the Taliban.

The Biden administration argues that no one “foresaw the collapse of the Afghan government and the hasty retreat of the Afghan forces.

Poll-tested decision-making?

Anchoring every discussion about the critical and dangerous situation on the ground is the polled sentiment that Americans overwhelmingly support a withdrawal from Afghanistan.

In April 2021, an Economist/YouGov poll of 1,499 adults nationwide found that 58% of those polled approved a Biden plan for withdrawal by September 11.

One supportive pollster elaborated further that 61% of military households, 52% of those currently serving, and 53% of those who previously served support the withdrawal.

By May, a Quinnipiac poll of 1,316 adults found 62% approving President Biden’s decision to withdraw all U.S. troops from Afghanistan by September 11, 2021. Of the military households polled, 59% agreed.

Then on August 9, 2021, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs reported that in their survey of 2,086 adults, 70% of Americans support the decision to withdraw forces from Afghanistan by September 11, 2021. Moreover, they found the support to be bipartisan. 77% of Democrats, 73% of Independents, and even 56% of Republicans agree.

It would certainly appear from the polling that most Americans and an increasing proportion supported this decision.

I would probably have added my agreement based simply on those facts if I had been polled and asked the question.

What if the question is wrong?

But what if the question was wrong?

What if our understanding of Afghanistan and the underlying details were flawed?

What if we were all wrong about what was happening and what was really at stake?

I am not a politician, have never worked in foreign policy, and have never served in the military. However, I am in the business of transformations (turn-around). As a shareholder in the world’s largest corporation (the USA), I know that the presentation by the current CEO and the previous one does not have the relevant facts to support the decision.

In conversations with CEOs about complex businesses, their sunk costs have little to do with business prospects. Instead, in my experience, those numbers create implicit management bias. Unfortunately, far too many business leaders want to hang on to businesses they have sunk a lot into.

In transformations, facts around the current reality and questions of the potential future are much more relevant. Therefore, I would instead focus on current expenditures, cash flow, and future potential.

The average invested over a long period or the total investment sunk are not the critical factors in the decision. In my experience only affects management bias toward the business. I would be more focused on the current expenditures and a projection of how those will change, related to the expected benefits.

In other words, how much the United States had already spent in Afghanistan and the lives already lost were not the most critical factors in deciding what to do about Afghanistan. Instead, current costs are much more relevant.

The problem with Polls

We make decisions based on the best and most relevant facts. So it’s worth exploring those in this case.

Politicians like to make decisions that are poll-tested. So perhaps they should be called Poll-iticians. But polls can be quite problematic.

Polls are not facts. They are opinion sentiments. Any severe policy decision buoyed with polls is as good as the poll itself. We would want to know that the pollsters asked the right questions of an informed audience.

I have spent almost a decade living in the Middle East. As a CEO, I had an Afghan-based communication business in my conglomerate portfolio for some time. It was an exciting business but a tiny part of my remit. So, I never visited Afghanistan and learned what I could about the country through conversations with the team that led that business, their reviews, and the experiences of those most recently there.

I would argue that my knowledge of Afghanistan is above that of the average American citizen. But I would also tell you that my knowledge of Afghanistan was woefully inadequate to answer the strategy question.

As a result, I undertook to find answers to the current reality and essential facts missing in any conversation I have heard on Afghanistan recently.

That’s the first problem with using polls to anchor a vital decision—especially regarding the USA’s strategy and future role in Afghanistan.

The first clue we may have a problem is found in this caveat by the Chicago Pollsters:

“American attitudes toward Afghanistan are somewhat sensitive to wording as well as policy. An April 2021 Fox News poll found that more Americans said the United States should keep some troops in the country for counterterrorism operations (50%) than said that the U.S. should remove all troops from the country (37%). And even though a solid majority of Americans in the 2021 Chicago Council Survey support the troop withdrawal, as recently as last January a Chicago Council poll showed that Americans were equally divided on whether the United States should have (48%) or should not have (49%) long term bases there. However, at the same time, two-thirds said that the war in Afghanistan had not been worth the costs (65%, 32% worth it).“

The Economist/YouGov poll referenced earlier asks the polled about their knowledge of Afghanistan. Specifically, they asked, “How closely are you following the news about the war in Afghanistan?”

Eleven percent (11%) of 1496 polled said they were following the news closely, thirty-five percent (35%) somewhat closely. Thirty-eight percent (38%) were not very close, and sixteen percent (16%) were not at all.

What facts are relevant?

Having been confronted recently with the reality that my understanding of Afghanistan, although better than the average American, was woefully inadequate, I wondered about those polled.

Let me say that again.

I would consider myself someone who has followed the Afghanistan war closely, and I would be the first to tell you I did not know the facts.

The fundamental question is whether the most relevant data would have driven different decisions.

Let’s explore that.

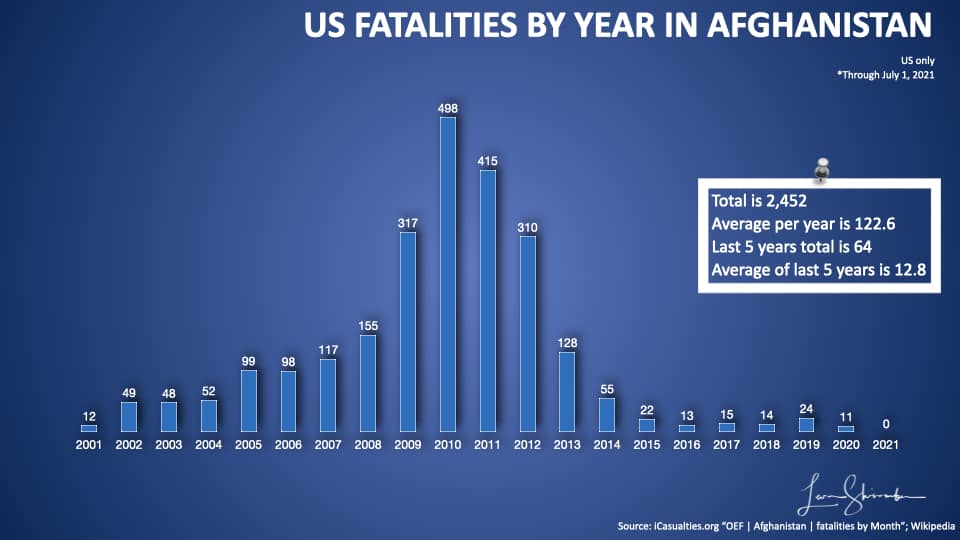

U.S. Fatalities in Afghanistan

The President says 2,448 have died. He also says we have spent $150 to $300 million per day.

The deaths are a factual statistic, and the expenditures are two broad estimates. Most would not argue with those assertions – too many casualties and a lot of cash over the last 20 years.

But what does that tell us about what is happening? Are we still incurring an average of 102 deaths a year? Are we still spending an average of $150 to $300 million daily?

Let’s unpack the Biden administration’s Afghanistan situation using facts and the best estimates we can find.

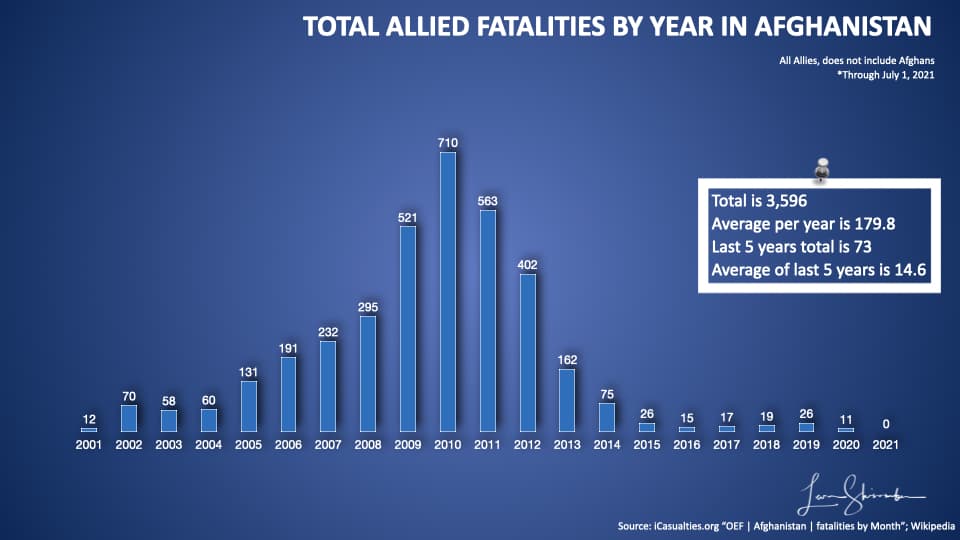

First, here is a chart that identifies the U.S. fatalities related to the war in Afghanistan since 2001 by year.

Identified on the chart are 2,452 American fatalities in and outside of Afghanistan. That number corresponds to the total referenced by the President.

What the President didn’t mention is that fatalities have plummeted since 2015. In the last five years, there were 64 fatalities, 2.7 percent of the total, and fatalities averaged 12.8 per year.

In the last five years, the average American yearly fatalities had dropped 92 percent from the first 15 years.

Last year, there were no American fatalities related to the Afghanistan war!

Let’s shift to the costs incurred in Afghanistan.

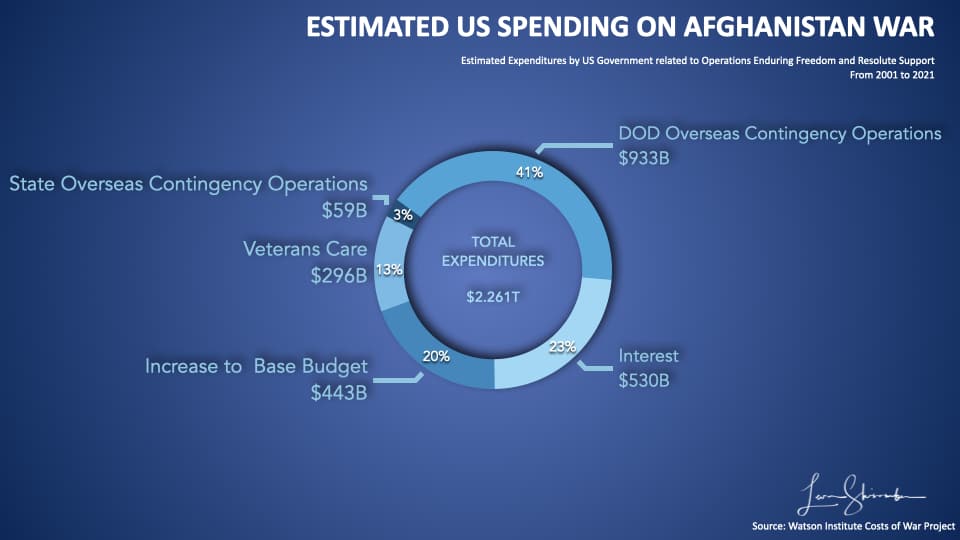

Expenditure on the Afghanistan War

There are wide variations in estimates of the cost of the Afghanistan war. However, the Costs of War Project provide one of the more rigorous and highest estimates of those costs at over $ 2.261 trillion, as identified in the following chart.

The $2.26T works out to approximately $300 Million per day, matching the upper end of President Bidens’ estimates.

I could not find any databases that break out these expenditures over time, so it’s challenging to pinpoint recent spending. Nevertheless, that is the most relevant information we need to understand.

Fortunately, we can use a proxy of deployments to get a sense of the spending over time.

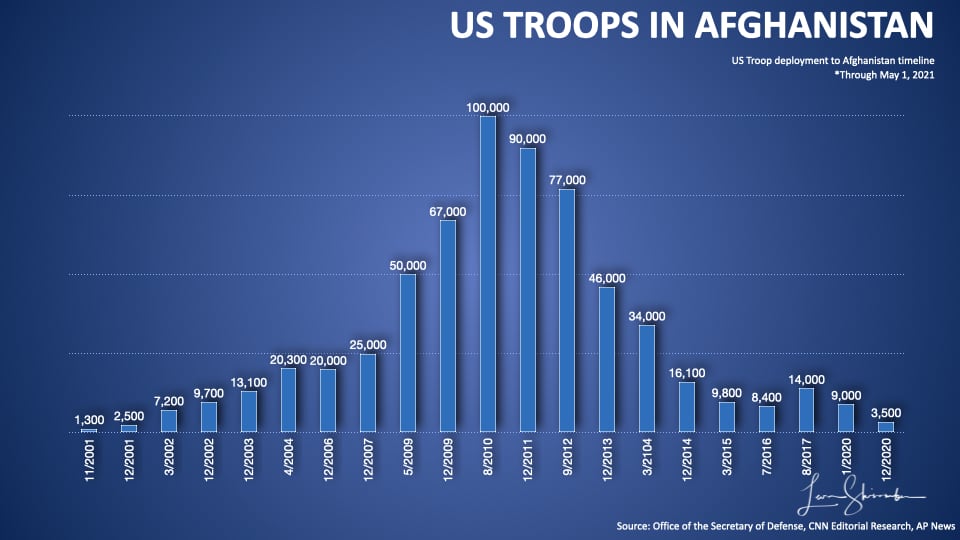

Troop Deployment to Afghanistan over time

We have credible data showing the number of troops deployed into Afghanistan over time, as identified in the following chart.

Identified on the chart are deployments that averaged approximately 28,500 per year for the last 20.

The deployed troop force averaged 7,480 per year in the last five years.

Our yearly deployment had dropped 80 percent from the first 15 years to the latest five years.

In the last year, our deployment was between 2,500 and 3,500, or a stunning 90 percent below the average!

In October 2013, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments reported the average cost per year per soldier deployed, averaging $1.3 Million before 2013 and rising to $2.1 Million in 2014.

These estimates are not just personnel salaries and benefits. They also include the other costs associated with supporting the deployment.

We would explain most of the expenditures using those estimated costs per soldier and extrapolating using actual deployment.

In the absence of year-by-year expenditures, I would suggest a strong hypothesis, supported by the deployment trends above, that recent expenses are dramatically lower than historically.

The importance of projections

The progress achieved is only half of the equation. The other half requires answering the question of sustainability.

Understanding possibilities and carving a strategy for the future requires a vision of operations, a clear articulation of the mission, relevant KPIs, using game theory to evaluate alternative competitive behavior, and so on. Rigorous analysis of options allows for better strategies than merely claiming the only choices were to exit entirely or increase troop strength dramatically.

We will push on without the ability to review the landscape of possibilities.

So, two of the four central pillars, namely the high fatalities, and expenditures, used in the rationale for exiting are shaky based on recent trends.

What are we trying to achieve?

The third and fourth pillars supporting an exit are that we completed the mission long ago, and there is no national security interest in Afghanistan.

Yes, we killed Bin Laden some time ago. And yes, we had significantly reduced the potential for Al Qaida to launch attacks in the USA.

According to a December 2020 Department of Defense (DOD) report, “A.Q.’s remaining core leaders pose a limited threat to U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan because they are focused primarily on survival.”

But I don’t recall a single presentation until now that our allied forces had eliminated the danger or that we could handle the risks better using over-the-horizon capabilities.

On the 10th anniversary of Bin Laden’s death, CNN interviewed Al Qaeda leaders via intermediaries. Here is what they said: “War against the U.S. will be continuing on all other fronts unless they are expelled from the rest of the Islamic world.“

The U.N. Security Council report dated May 20, 2021, has this to say about Al Qaida in Afghanistan:

“The Taliban and Al-Qaida remain closely aligned and show no indication of breaking ties. ”

“Al-Qaida is resident in at least 15 Afghan provinces.”

“Al-Qaida maintains contact with the Taliban but has minimized overt communications with Taliban leadership in an effort to “lay low” and not jeopardize the Taliban’s diplomatic position vis-à-vis the Doha agreement.”

“Al-Qaida’s own strategy in the near term is assessed as maintaining its traditional safe haven in Afghanistan for the Al-Qaida core leadership.“

The Brookings think tank, generally left-leaning, said the following on May 14 regarding the risks: “The U.S. withdrawal will limit the U.S. ability to strike the al-Qaida core in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The lack of U.S. troops is likely to hinder efforts to strike al-Qaida directly — but also make it difficult to determine whether the Taliban is cheating on its commitment to halt al-Qaida from conducting international attacks.“

As to the national security interest, I am not a policy expert, but I wonder why an air force base in Afghanistan is no longer necessary. We know it takes multiple hours to deploy drone assets from their base in the middle east to Afghanistan.

Yes, we will have over-the-horizon capabilities, but those will be dramatically less effective than being based in Bagram. In addition, long-distance crewed overflights will be extremely risky without the ability to rescue crews shot down or experiencing malfunctions behind enemy lines.

Anyone who claims that we were in Afghanistan for 20 years merely for that mission will have significantly understated our efforts.

Other Strategic Interests?

John F. Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), issued a report in August 2021 titled “What we need to learn: Lessons from Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction.“

Yes, that’s right, for a long time, the USA has been nation-building and reconstructing Afghanistan.

The report says the following:

“The U.S. government has now spent 20 years and $145 billion trying to rebuild Afghanistan, its security forces, civilian government institutions, economy, and civil society. The Department of Defense (DOD) has also spent $837 billion on warfighting, during which 2,443 American troops and 1,144 allied troops have been killed and 20,666 U.S. troops injured. Afghans, meanwhile, have faced an even greater toll. At least 66,000 Afghan troops have been killed. More than 48,000 Afghan civilians have been killed, and at least 75,000 have been injured since 2001—both likely significant underestimations.“

“The extraordinary costs were meant to serve a purpose—though the definition of that purpose evolved over time. At various points, the U.S. government hoped to eliminate al-Qaeda, decimate the Taliban movement that hosted it, deny all terrorist groups a safe haven in Afghanistan, build Afghan security forces so they could deny terrorists a safe haven in the future, and help the civilian government become legitimate and capable enough to win the trust of Afghans. Each goal, once accomplished, was thought to move the U.S. government one step closer to being able to depart.“

The statements above suggest a far broader mandate than the President is using.

I know we stubbornly believe that the USA is not good at nation-building. History belies this assumption. Japan, Germany, Iraq, and Korea have all been messy but hugely successful nation-building missions. I will come back to this momentarily.

I need to point out that the Biden plan did not contemplate a complete withdrawal. Instead, the planners assumed we would continue to have an embassy supporting a functioning Afghanistan government.

The exit of Bagram is explained as a rational decision based on a preference for using HKIA, which is closer to the embassy.

Despite public proclamations that the planners considered every possibility, it would appear that no one believed a rout of Afghanistan by the Taliban was probable.

Do we understand the stakeholders?

Emerging from the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban is a fifth pillar to explain the “right” decision to exit. That pillar is, “If they are not willing to stand up and fight for their country, why should we.”

When our officials stand at a podium and make this shameful statement, they suggest that Afghans were unwilling to die for their country. That is far from the truth and bears an examination of the facts.

The Afghan Military

Let me repeat a statement from SIGAR that you may have casually scanned a few paragraphs earlier.

“Afghans, meanwhile, have faced an even greater toll. At least 66,000 Afghan troops have been killed. More than 48,000 Afghan civilians have been killed, and at least 75,000 have been injured since 2001—both likely significant underestimations.”

The Afghan military has suffered 20 times as many fatalities as the Allied forces.

The Afghans may not be great fighters as the well-trained Allied forces, but they were not cowards.

So why did the Afghanistan armed forces fold so easily?

One might argue that in agreeing to negotiate with the Taliban directly and without the ruling Afghanistan government, Trump elevated the importance of the Taliban and undermined the government’s legitimacy.

But there’s more to the collapse than this diplomatic blunder.

To shed light on the real catalyst, we need to reflect on the stated views of our closest ally in the Afghanistan fight.

Our Allies

Let me remind you that the USA was not alone in fighting in Afghanistan. We had an allied team.

The preceding chart shows that the total number of Allied fatalities, not counting the Afghans, was 3,596 versus 2,452 Americans.

Of the additional 1,144 fatalities, the United Kingdom paid the heavy price of 40% of those (486 deaths).

The United Kingdom has been a stalwart partner and shouldered a heavy burden in the Afghanistan war.

Here is how Tony Blair, the former U.K. Prime Minister that wholeheartedly supported the U.S. War on Terror, interprets the turn of events:

“America acted unilaterally over Afghanistan – actually maybe that should be Joe Biden acted unilaterally. The administration was not much interested in what the U.K. thought. Mr Biden, from what I have been told, was not much interested in the red flags being raised by his intel community and military top brass, or by the warnings delivered from London. He wanted out. The warnings of H.M. Government – and my understanding is they were made strenuously – fell on deaf, indifferent ears in Washington.”

“In those circumstances – and let me depersonalise this – what is a British prime minister to do? If the 800lb gorilla is going to leave the room, what is the much smaller primate meant to do? The idea that the British armed forces could have swarmed in to fill the vacuum left by a U.S. withdrawal is unrealistic.“

“The Ministry of Defence (MoD) with the number of British servicemen and women in situ would have little option but to withdraw – or face heavy casualties that would have in all probability failed to stem the Taliban advance. In American football terms, the U.S. had called the play; there was little for the British to do but fall into line.“

Our closest, bravest, most capable ally would not fill the vacuum left by the U.S. decision. So why on earth should we expect the Afghans to commit suicide?

So there we are. We have explored the facts and found the prevailing arguments short of credible.

Let’s ask the question again. Given these facts, should the American public support an Afghanistan withdrawal?

But before you answer, let me leave you with this final thought. A picture of Afghanistan since we first got there.

The Afghan citizens

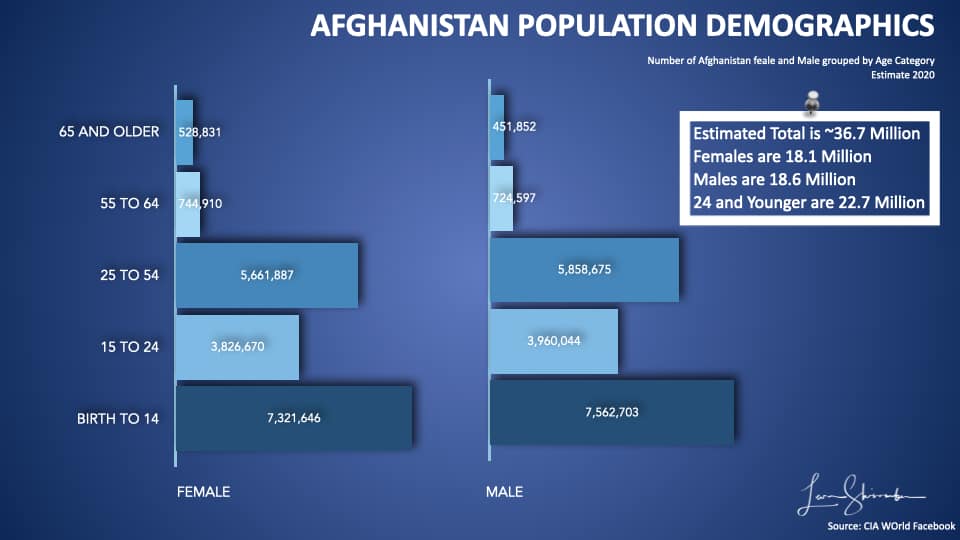

In 2001 Afghanistan was a country of 21.6 Million citizens. In 2021 the population of Afghanistan has grown by 18.3 million to approximately 39.9 Million. Below is a recent chart of the population pyramid of Afghans by gender and age groups.

A stunning 22.7 million (62%) Afghan population is 24 years and younger. This group has no memory or experience of life under the Taliban.

The UNHCR tells us that since 2002, nearly 5.3 million Afghan refugees have returned to Afghanistan. Only 2 million registered Afghan refugees remain in Pakistan and Iran.

Literacy has risen from 8% in 2001 to 43%.

39% of girls were attending school in 2017 versus the compared to the estimated 50,000 in 2001.

Would relevant facts change your decision?

I know my answer to the question of support for a complete exit from Afghanistan.

President Biden has claimed depth in foreign policy and intends to bring back American diplomacy and allied collaboration to cherished relationships. If there were any Trump policies that Biden should ignore, this one bears the most merit.

Now it’s your turn. So let me ask you:

Do you feel the world is safer from terrorism now than two weeks ago?

What should we invest in protecting the lives of 11.1 million Afghan women 24 years and younger from the Taliban?

Given the facts, would you have supported a September 11, 2021, complete withdrawal from Afghanistan?

Is Afghanistan Lost? The German View

Postscript: These are conversations we never had and should have had earlier. Sadly, instead of the USA celebrating a withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan by 9/11/2021, it is more likely that the Taliban will be celebrating its return to power in Afghanistan on the 20th anniversary of a day many of us will never forget.

Hope is not a strategy, yet we hope the Taliban allow the Allies to evacuate their personnel and endangered Afghans. And, here we are, hoping that other nefarious forces don’t act on the opportunity to attack those helpless trying to evacuate.

I would encourage all to support the private and public efforts to assist those behind Taliban lines and pray for a safe evacuation of those wishing to leave.

As always, please let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

Sources:

President Biden 8/2/2021 Transcript from Whitehouse.Gov

April 2021 Economist/YouGov Poll

August 2021 Chicago Council Survey

Watson Institute Cost of War Project

Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments Assessment of Costs Per Soldier

December 2020 Department of Defense (DOD) report

CNN April 2021 interview of Al Qaeda leaders

U.N. Security Council report dated May 20, 2021

Brookings May Comments on Al Qaeda

SIGAR Report What we need to learn: Lessons from Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction

Tony Blair’s Comments on Afghanistan Exit

Another fascinating and insightful essay, Leon. I don’t think anyone believes anything a politician says (unless it supports their preexisting ideas). The plight of the young people with no memory of Taliban rule is both scary and promising if, like water, they can find and take advantage of weaknesses and cracks and gradually lead change from the inside. I’m curious if you considered the thoughts of Julian Assange, ten years ago or so, “US goal is an endless war, not a successful war”? He suggested that the goal was to extract taxpayer money to support a transnational military-industrial complex for as long as possible.

Mark, as always, you are spot-on: The problem is the unwavering loyalty shown to parties that are not interested in what’s right for the average American. To be sure there is an economic rationale for some, but it’s even more interesting how often people are loyal despite the policies against their self-interest.

Hope we will be able to catch up in person soon.