This is a story about how we make choices, and why we frequently get them wrong. It’s a story about experts who, like us, do the same. It also addresses how experts criticize those who offer correct solutions and how to tell who actually deserves your trust.

Sometimes we stare so long at a door that is closing that we see too late the one that is open.

Alexander Graham Bell

- The Monty Hall Problem Explains Our Worst Decisions

- The Problem That Broke Mathematics

- Why Smart People Got It Wrong

- The Cost of Wrong Doors

- Why We Keep Choosing Wrong

- The Pattern Behind the Mistakes

- The Hardest Question: Who Do You Trust?

- What the Experts Missed

- The Lesson Nobody Wanted to Learn

- Reference Sources

The Monty Hall Problem Explains Our Worst Decisions

In 1990, a magazine columnist named Marilyn vos Savant answered a simple probability puzzle. She was right. But 10,000 people wrote to tell her she was wrong.[1]

Many of them had PhDs. Some were mathematics professors. One Georgetown professor wrote: “How many irate mathematicians are needed to get you to change your mind?”[1]

The remarkable thing: Marilyn vos Savant had the highest measured IQ on record at the time. Yet that credential meant nothing. The PhDs were unmoved by the source. They only cared about the conclusion, which they thought was absurd.

Even Paul Erdős—one of history’s greatest mathematicians—couldn’t accept the correct answer until he saw a computer proof.[2][3]

The problem was simple. The solution was simple. But brilliant people couldn’t see it.

This tells us something important about how we make decisions. And why so many of those decisions turn out badly. It also teaches us the hardest lesson of all: credentials are not the same as correctness, and expertise without transparency is just authority.

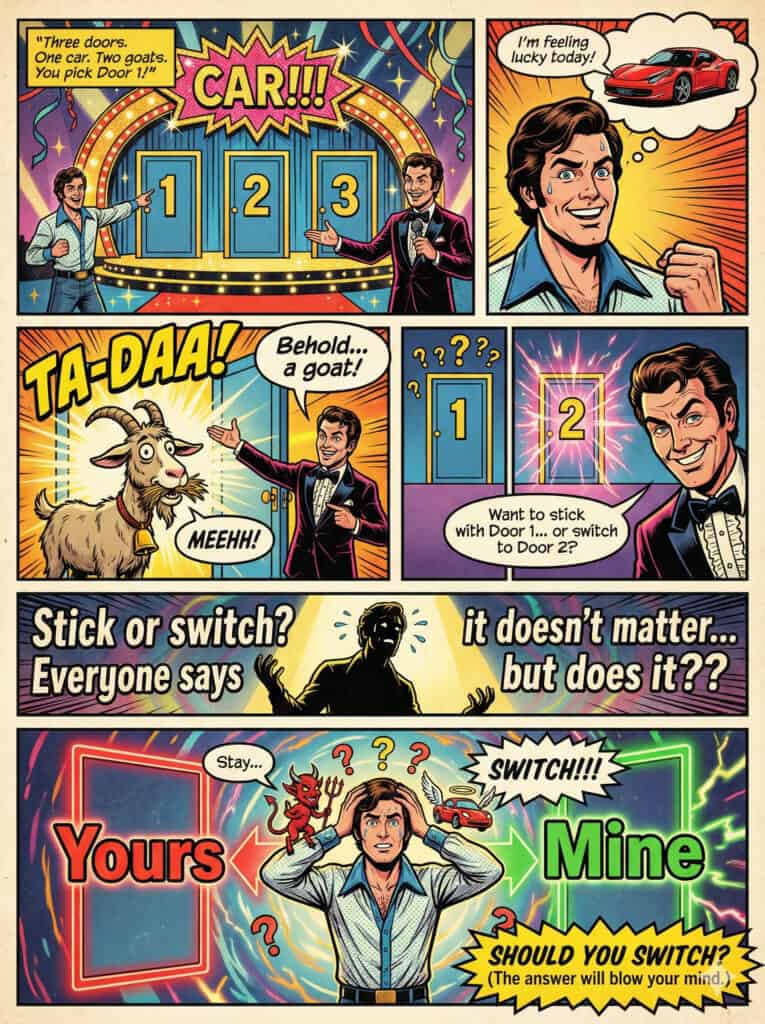

The Problem That Broke Mathematics

Here’s what Marilyn answered:

You’re on a game show. You are presented with three doors. Behind one is a car. Behind the others are goats.

You pick Door 1. The host opens Door 3, revealing a goat. He asks: “Want to switch to Door 2?”

Should you?

Let’s assume there’s nothing nefarious going on. Monty is playing a fair game and always offers to switch. So do not assume the offer to switch is psychological pressure to switch a winning hand. [See Note at bottom]

Would you?

Most people say it doesn’t matter. Two doors left. Fifty-fifty odds. Why switch?

But that’s wrong. You should always switch. It doubles your chances from 1 in 3 to 2 in 3. [1][4][5]

The math is simple. When you first picked, you had a 1-in-3 shot. That hasn’t changed. The host can’t open the door with the car. He must show you a goat. His action gives you information.[5][6]

If you were initially wrong, which happens 2 out of 3 times, switching wins. If you were initially right, which occurs 1 out of 3 times, switching loses. Simple.

Here’s another way of thinking about it. Now that you have picked your door, Monty asks if you want to switch it for his two. Who wouldn’t want two chances rather than one? Of course you would!

That is precisely what is happening above, you are trading your door for the two Monty has, except Monty knows what’s behind every door, and is making it more dramatic by revealing a door that has a goat in one of his two.

Still struggling? Assume there are 10 doors; you pick one, and Monty opens 8 with goats. Would you stick with yours or switch to Montys?

Why Smart People Got It Wrong

The mathematicians who disagreed with Marilyn shared the same mistake. They assumed the two remaining doors meant equal odds.[1][5]

Dr. Robert Sachs from George Mason University explained it this way: “Since you seem to enjoy coming straight to the point, I’ll do the same. You blew it! If one door is shown to be a loser, that information changes the probability of either remaining choice, neither of which has any reason to be more likely, to 1/2.”[1]

He was confident. He was credentialed. And he was completely wrong.

Notice what Sachs did not do: he did not walk through the sample space. He did not ask what happens in each of the three equally likely scenarios. He did not show his work. He just restated his intuition and signed it with his title.

The problem tricks our brains. We see two options and assume equal probability for each. This is called equiprobability bias. It feels right. It’s intuitive. And it leads us astray.[5]

Even Paul Erdős—who published over 1,500 mathematical papers—fell for it. When shown the solution, he said: “No. That is impossible.”[2][3]

His friend tried to convince him three different ways. First with decision trees. Then with Bayes’ Theorem. Neither worked. Only after running 100,000 computer simulations did Erdős grudgingly accept the truth.[2][3]

Why did he struggle? One theory: “Erdős had this idea of probability as being attached to physical things.” He saw probability as a property of objects, not as information that changes based on evidence.[5]

This is how most of us think about probability. And it explains why we make terrible financial decisions.

The Cost of Wrong Doors

Every day, millions face choices that look like the Monty Hall problem. They see what appears to be equal options. They rely on intuition. And they pick the wrong door.

Consider the lottery.

Americans spent $103 billion on lottery tickets in 2023, and industry analysts project the market will reach $194 billion in 2025. That’s more than most Americans spend on movies, music, sports tickets, and books combined.[7]

The poorest Americans spend the most. People making under $10,000 spend an average of $597 per year, or 6% of their income. Those in the lowest fifth of earners play the lottery 26 days per year. Everyone else plays 10 days or fewer.[7][8]

The math is brutal. Scratch tickets return about 50 cents on the dollar. Powerball and Mega Millions are worse. You’re more likely to be struck by lightning than to win.[7][8]

Yet 40 million American households play habitually, spending about $2,500 per year. For low-income families, this often represents a large fraction of discretionary income. One in five Americans thinks the lottery is the only way to accumulate significant savings. [7][8]

They’re switching to the wrong door. Every single time.

The Payday Loan Trap

Twelve million Americans use payday loans each year. The average borrower takes out eight loans of $375 each. They spend $520 on interest alone.[9]

The average APR? 391%.[10]

In Texas, it’s 664%, more than 40 times the average credit card rate.[11]

Most borrowers use payday loans not for emergencies, but for ordinary living expenses over months. They’re in debt about five months of the year. More than 80% of payday loans are rolled over or followed by another within two weeks.[9][12]

Who uses them? People without four-year degrees. Renters. Those earning under $40,000. People who are separated or divorced. And 81% have full-time jobs.[9]

They see an immediate need. They see an available solution. They don’t calculate the real cost. They switch to the most expensive door available.

This is equiprobability bias in action again. They see two doors: “Crisis” or “Cash.” They assume the risks are manageable. They don’t calculate the real cost. They switch to the most expensive door available.

The College Calculation

Higher education works the same way. Students see college as a good choice. Many assume all degrees offer similar returns.

The reality is different.

The median bachelor’s degree has an ROI of $160,000. But 23% of bachelor’s programs yield negative ROI. Nearly half of master’s degree programs leave students financially worse off.[13]

The gap between doors is massive:

Table – Example Lifetime ROI by Degree Path [14]

| Degree Path | Lifetime ROI |

|---|---|

| Finance | 1,842% |

| Computer Science | 1,753% |

| Electrical Engineering | 1,515% |

| Family & Consumer Science | -38.95% (Loss) |

| Liberal Arts/Humanities | -42.78% (Loss) |

| Education | -55.43% (Loss) |

Students borrow tens of thousands to open doors that lead nowhere. They trust intuition over information. They assume their personal exception will overcome statistical reality.

Around 30% of all federal Pell Grant and student loan funding supports programs that yield no return on investment.[13]

This is where the Monty Hall lesson becomes most urgent. Many education experts insist that college is always worth it. But they rarely show you the first-principles calculation. They ignore the time value of money, treating a dollar earned 30 years from now as equal to a dollar today. They ignore opportunity cost—the wages you’re giving up by sitting in class instead of working.

A serious evaluation requires an assessment of the actual cash flows over time. At what discount rate? Which realistic alternative are you comparing against? If an expert cannot answer those questions clearly, their conclusion is not yet decision-grade, no matter how prestigious the institution.

For the last 30 years, a third of college graduates have been working in jobs that do not require a degree. Read The Damage When Smart People Miss Critical Insights? A $1.6 Trillion Blind Spot[32]

The Retirement Gamble

58% of American workers say they’re behind on their retirement savings. More than one in four families nearing retirement have nothing saved at all.[15][16]

For those who have saved something, the median balance is $87,000.[15]

Nearly half of American households have no retirement savings accounts. Among low-income workers, 75% lack access to any retirement plan.[17][18]

And 31.9 million 401(k) accounts have been left behind or neglected, with an average balance of $66,691. That’s $2.1 trillion sitting forgotten.[19]

They had the right door open. They walked away anyway.

The Credit Card Spiral

Total U.S. credit card debt reached $1.233 trillion in 2025. The average American with credit card debt carries a balance of $6,523 to $7,321, depending on the source. [20][21][22][23]

What is the average APR on cards with balances? 22.76%. Some cardholders pay much higher rates.[20]

Credit card delinquency rates hit 3.05% in 2025, the highest since 2012. This means millions are struggling to make even minimum payments.[22]

Nearly 57% of Americans say bad online financial advice led them to make regrettable decisions. Thirty-nine percent lost $250 or more. Eighteen percent lost over $1,000.[24]

Why do people struggle with credit cards? Behavioral economics has answers. When we use plastic instead of cash, our brains don’t register the money as really spent. We hand over the card. The clerk gives it right back. The result feels invisible until the bill arrives a month later.[25]

“The mind is almost saying ‘I’m getting it for free,'” one researcher explains.[25]

Think of it like the game show. We focus on the immediate purchase or the rewards points, the visible goat, and ignore the compounding interest hidden behind the door. We pick the door that feels the least painful. Then we’re shocked when it costs more than we imagined.

Why We Keep Choosing Wrong

Research reveals Americans struggle with basic financial literacy. About half of U.S. adults lack financial literacy, and this number has held steady for eight consecutive years.[26]

Many don’t understand compound interest or inflation. This was a factor in the financial crisis. Households took on debt they couldn’t afford. Even today, improper use of household debt continues to explain the slow economic recovery.[27]

But the problem isn’t just knowledge. It’s psychology.

We exhibit confirmation bias, seeking information that confirms our existing beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. We fall for the bandwagon effect, supporting things simply because others do. We assume our views are more common than they actually are due to the false consensus effect.[28][29][30]

We make decisions based on how choices are presented, not their inherent quality. We procrastinate. We lack self-control. We don’t adequately value the future relative to today. [27][31]

We exhibit overconfidence, thinking we can beat the market when few can. We feel loss more intensely than gain. We sell winners but keep losers. We assume the past predicts the future. [27]

All of these biases make us vulnerable to bad decisions. And unlike the Monty Hall problem, these decisions cost us real money.

The Pattern Behind the Mistakes

Look at the common thread. In every case, equiprobability bias blinds us to the real odds:

- The lottery player sees two doors, win big or lose $2, and misjudges the odds.

- The payday loan borrower sees two doors: solve today’s crisis or default on rent, and ignores long-term costs.

- The college student sees two doors: a degree or no degree, without calculating which degree matters.

- The worker sees two doors: save for retirement someday or spend today, and picks the immediate reward.

- The credit card user sees two doors: buy now with plastic or wait to save cash, and chooses invisible pain over visible sacrifice.

In every case, we make the same error that the mathematicians made with Marilyn’s puzzle. We see what appears to be equal choices. We trust our intuition. We ignore the information available to us.

The Hardest Question: Who Do You Trust?

The Monty Hall story leaves us with an uncomfortable problem.

If world-class mathematicians can be confidently wrong about a three-door puzzle, how are the rest of us supposed to judge who to believe?

When Marilyn gave the correct answer, almost all the visible authorities lined up against her. Professors with PhDs wrote on university letterhead to say she had “blown it,” and they used their credentials as proof.

They rarely showed their whole reasoning. They mostly repeated an intuition: “Two doors left means 50–50.”

That is the core danger. The problem is not that experts exist. The problem is that we often treat a résumé as a substitute for thinking. We must distinguish between authority (trust me because of my title) and expertise (trust me because I can show you the proof).

Trust the Explanation, Not the Résumé

So how do you decide between Marilyn and the math department?

You start by flipping the default rule: explanations first, credentials second.

Ask a few simple questions:

Do they restate the problem clearly? Marilyn made sure the rules were explicit: Monty always opens a goat door and always offers a switch. Many critics quietly changed the rules to match their intuition.

Do they show their work in plain language? You do not need equations to understand that switching wins whenever your first guess was wrong, which happens 2 out of 3 times. Good experts can walk you through that. They can make it clear enough that you could teach it to someone else.

Do they face the obvious tradeoffs? In Monty Hall, the tradeoff is simple: stick with your 1-in-3 door or trade it for Monty’s 2-in-3. In real life, the tradeoffs are money, time, risk, and alternatives.

If an expert will not spell those things out or makes you feel silly for asking, that is a warning sign.

The most trustworthy experts behave the opposite way. They slow down. They define terms. They welcome challenges.

First Principles Beat Vague Authority

This matters most where the stakes are highest, for example, college, debt, and retirement.

Take college ROI. Many expert reports sound impressive. They talk about “lifetime earnings premiums” and “college wage gaps.” Few start from first principles: cash in, cash out, and what else you could have done with your time and money instead.

A basic first-principles checklist looks like this:

Time value of money. A dollar earned 30 years from now is not worth a dollar today. Serious ROI work discounts future earnings to present value; many optimistic narratives do not.

Opportunity cost. Four years in school means four years not earning full-time wages. For many students, that foregone income is as significant as the tuition bill.

Real alternatives. The proper comparison is not “college vs. nothing.” It is “this program vs. working now, a cheaper program, or a shorter credential.”

When an “expert” says, “College is always a good investment,” you can now ask: Over what time frame? At what discount rate? Including which costs? Compared to what path? If they cannot answer, they have not solved the problem. They have just picked a door.

A Simple Rule for Ordinary Decisions

You do not need to become a statistician to protect yourself. You only need one habit:

Trust the explanation you can trace, not the expert you have to take on faith.

In practice, that means:

- When you read advice on loans, degrees, or investments, look for the math you can sketch on a napkin: cash flows over time, interest rates, probabilities. If you cannot see it, be cautious.

- When someone with a big title makes a strong claim, ask yourself, “What are they leaving out?” Time, risk, opportunity cost, or alternatives are the usual missing doors.

- When two authorities disagree, side with the one who helps you understand the structure of the problem well enough that you could explain it to a friend.

Monty Hall was never really about goats and cars. It was a stress test of how we handle expertise.

The people who passed were not the ones with the most letters after their names. They were the ones who could slow down, do the simple math, and change their mind when the numbers told them to.

What the Experts Missed

The mathematicians who attacked Marilyn shared another trait: they trusted their expertise so completely that they stopped thinking.

They had PhDs. They taught at universities. They published papers. Surely a magazine columnist couldn’t know better.

Dr. Everett Harman from the U.S. Army Research Institute wrote: “You made a mistake, but look at the positive side. If all those Ph.D.’s were wrong, the country would be in some very serious trouble.”[1][4]

Turns out, the PhDs were wrong. And the country is in very serious trouble.

Americans collectively hold $1.233 trillion in credit card debt. We’ve abandoned $2.1 trillion in retirement accounts. We spend $194 billion yearly on lottery tickets with negative expected value. We pay $2.4 billion in payday loan fees in a single year.[31]

We fund college degrees that guarantee financial loss.

We make economic decisions based on misleading online information.

We struggle to pay for basic expenses while spending thousands on statistical impossibilities.

The pattern is clear. When faced with probability, we trust our feelings over math. When offered good advice, we ignore it if it contradicts intuition. When presented with evidence, we double down on being wrong.

The Lesson Nobody Wanted to Learn

Marilyn vos Savant later reflected on the controversy: “It promotes a dandy demonstration of a human frailty, the disbelief that we could be wrong and the tenacity, sometimes aggrieved, with which we hold our earlier judgments, especially when we feel certain.”[5]

This frailty costs Americans dearly.

It’s not that we lack information. We have access to compound interest calculators, ROI data for every college major, odds for every lottery game, and APR disclosures for every loan.

The information exists. We don’t use it.

We trust our gut. We follow the crowd. We believe we’re exceptions to statistical rules. We assume visible options carry equal probability.

And we keep picking the wrong door.

The solution isn’t more complex. It’s actually simpler than we want to admit. When facing a decision with financial consequences, do the math. Ignore intuition. Look at actual data. Calculate real costs.

Switch doors when the evidence says to switch.

But that requires something harder than solving a probability puzzle. It requires admitting we might be wrong. It requires valuing evidence over feeling. It requires accepting that our initial choice might be mistaken.

Even brilliant mathematicians struggled with that, even after seeing the proof.

Marilyn vos Savant proved that being right often feels like being wrong.

The real question isn’t whether we can learn to pick the right door. It’s whether we’re willing to accept we’ve been wrong about which door to choose.

To stop walking away with the goat, we have to be brave enough to look at the math, ignore the authority figures shouting at us, and switch doors.

Notes

The way Marilyn originally phrased the question, there was no clarity that Monty played a fair game. In that case, Monty Hall could reveal the goat if that was picked, or offer you the chance to switch when you had a winning hand. That changes the math problem.

The experts’ objections were not based on this potential complication. In every case, they based it on a misunderstanding of the probability. I chose to clarify above for precision and for you to explore the probability problem, without psychological considerations.

The predecessor to the “Monty Hall Problem” is the “Three Prisoner Problem,” which Martin Gardner analyzed in 1959 for Scientific American.[1]

Throughout this article I have used American examples. However, the problem of picking the wrong doors is not limited to Americans. It is a global problem.

Reference Sources

- Tierney, John. “Behind Monty Hall’s Doors: Puzzle, Debate and Answer?” The New York Times, 21 July 1991, https://www.nytimes.com/1991/07/21/us/behind-monty-hall-s-doors-puzzle-debate-and-answer.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Ananthaswamy, Anil. “The Monty Hall Problem: Could an LLM Have Convinced Paul Erdős?” Why Machines Learn, 28 Sept. 2024, https://anilananthaswamy.com/why-machines-learn-codebook-blog/monty-hall. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Vazsonyi, Andrew. “Monty Hall, Paul Erdős, and Monte Carlo.” Midwest SAS Users Group Proceedings, 2010, https://www.mwsug.org/proceedings/2010/stats/MWSUG-2010-87.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Institute of Mathematics and its Applications. “Don’t Switch! Why Mathematicians’ Answer to the Monty Hall Problem is Wrong.” IMA, 6 Oct. 2022, https://ima.org.uk/4552/dont-switch-mathematicians-answer-monty-hall-problem-wrong/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Bellows, Allen. “Why Almost Everyone Gets the Monty Hall Probability Puzzle Wrong.” Scientific American, 1 Oct. 2019, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-almost-everyone-gets-the-monty-hall-probability-puzzle-wrong/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Frost, Jim. “Monty Hall Problem: Solution Explained Simply.” Statistics How To, 12 May 2024, https://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-and-statistics/monty-hall-problem/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Lottery Statistics: How Many People Play Lottery In The U.S.?” Search Logistics, 27 Mar. 2025, https://www.searchlogistics.com/learn/statistics/lottery-statistics/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Bernal, Les. “Lottery Tickets: Poor Rich Income Powerball Mega Millions Jackpot Odds.” Fortune, 4 Apr. 2024, https://fortune.com/2024/04/04/lottery-tickets-poor-rich-income-powerball-mega-millions-jackpot-odds-les-bernal-stop-predatory-gambling/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Payday Loan Industry Statistics 2025: Market Size, Growth, and Consumer Behavior.” CoinLaw, 15 Aug. 2025, https://coinlaw.io/payday-loan-industry-statistics/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “How Payday Loans Work.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 31 July 2019, https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2019/july/how-payday-loans-work. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Map Shows Typical Payday Loan Rate in Each State.” CNBC, 16 Feb. 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/02/16/map-shows-typical-payday-loan-rate-in-each-state.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “2025 US Payday Loan Debt Statistics.” DebtHammer, 11 June 2023, https://debthammer.org/payday-loan-debt-statistics/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Goudreau, Jenna. “Does College Pay Off? A Comprehensive Return On Investment Analysis.” Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, 2023, https://freopp.org/whitepapers/does-college-pay-off-a-comprehensive-return-on-investment-analysis/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Is College Worth it? | Return on Investment Analysis of College Degree.” EducationData.org, 30 Dec. 2024, https://educationdata.org/college-degree-roi. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Federal Reserve. “Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, 1989 – 2022, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scf/dataviz/scf/chart/#series:Retirement_Accounts;demographic:all;population:1;units:median Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Bankrate’s 2025 Retirement Savings Report.” Bankrate, 2025, https://www.bankrate.com/retirement/retirement-savings-report/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Economic Innovation Group. “Who’s Left Out of America’s Retirement Savings System?” EIG, 2023, https://eig.org/whos-left-out-of-americas-retirement-savings-system/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Retirement Savings.” USA Facts, 2024, https://usafacts.org/data-projects/retirement-savings/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Americans Have Abandoned 31.9 Million 401(k)s, with Average Balances of $66,691.” Yahoo Finance, 15 Oct. 2025, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/americans-abandoned-31-9-million-101600271.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “2025 Credit Card Debt Statistics.” LendingTree, 6 Nov. 2025, https://www.lendingtree.com/credit-cards/study/credit-card-debt-statistics/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Average American Credit Card Debt in 2025.” The Motley Fool, 17 Nov. 2025, https://www.fool.com/money/research/credit-card-debt-statistics/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Credit Card Statistics.” Ramp, 2025, https://ramp.com/blog/credit-card-statistics. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Household Debt and Credit Report.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2025, https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Bad Online Advice Leads Majority of Americans to Make Regrettable Financial Decisions.” CFP Board, 10 June 2025, https://www.cfp.net/news/2025/06/bad-online-advice-leads-majority-of-americans-to-make-regrettable-financial-decisions. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “How Behavioral Economics Explains 6 Common Money Mistakes.” Nasdaq, 7 Jan. 2014, https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/how-behavioral-economics-explains-6-common-money-mistakes-2014-01-07. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “How Financially Literate Is America – Key Stats by Age (2025).” Carry, 21 Oct. 2025, https://carry.com/learn/how-financially-literate-is-america-key-stats. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “The Behavioral Economics Behind Americans’ Paltry Nest Eggs.” Quartz, 2014, https://qz.com/165894/the-behavioral-economics-behind-americans-paltry-nest-eggs. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Cognitive Biases in Voting.” Sustainability Directory, https://climate.sustainability-directory.com/term/cognitive-biases-in-voting/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “11 Cognitive Biases That Influence Political Outcomes.” World Economic Forum, 12 Aug. 2020, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2020/08/11-cognitive-biases-that-influence-political-outcomes/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Cognitive Biases in Politics.” St. Louis Community College Highlander, 2023, https://www.stlcch.com/blog/cognitive-biases-in-politics. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Behavioral Economics and Financial Well-Being.” Social Security Administration, Aug. 2000, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v70n4/v70n4p1.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- “Down the Drain: Payday Lenders Take $2.4 Billion in Fees from Borrowers in One Year.” Center for Responsible Lending, 2023, https://www.responsiblelending.org/research-publication/down-drain-payday-lenders-take-24-billion-fees-borrowers-one-year. Accessed 4 Dec. 2025.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York Underemployment rates for Recent College Graduates https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market#–:explore:underemployment Accessed 4 Dec. 2025