When the smart people you know give you an unconditional recommendation, you should pay attention.

My friend Terrence Burns doesn’t recommend books lightly. When he handed me Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, I knew I was in for serious intellectual stimulation.

Terrence is smart and successful.[1] He operates in a completely different league. He’s the guy who shaped Global sports marketing and who countries call when they want to win Olympic bids. China hired his firm, and they won.

So when someone like that says, “Read this,” the book went to the top of my reading list.

It’s a book I will read slowly. I have completed Dan Brown’s Secret of Secrets (689 pages), during which I have only covered 56 pages of Breakneck. It’s not exactly a breakneck pace, but here’s why.

The author Dan Wang spent years working as a consultant in China, watching the country transform in real time. Right in the first chapter, Wang made a claim that stopped me cold:

China is run by engineers. Lawyers run America.[2]

Eight words that could reframe everything about global competition.

I sat back in my seat and thought: Is that actually true? And if it is, what does it mean for America’s future?

“When I was growing up, my parents told me, ‘Finish your dinner. People in China and India are starving.’ I tell my daughters, ‘Finish your homework. People in India and China are starving for your job.”

Thomas Friedman

- The Filters That Change Everything

- The Numbers Nobody Wants To Talk About

- The PhD Pipeline: Where The Future Gets Built

- Hold On, Here’s The Plot Twist – Quality Still Matters

- The Real Problem: Where Does Talent Flow?

- What Makers Do vs. What Regulators Do

- The Strategic Advantage We’re Squandering

- Why This Is A National Security Crisis

- How We Got Here (And Why It Matters)

- What’s At Stake

- Two Big Ideas to Rebalance America’s Talent

- What You Can Do

- The Bottom Line

- Postscript

- Reference Sources

The Filters That Change Everything

I’ve written before about my four-filter system for deciding what deserves my time: Is it true? Is it kind? Is it necessary? Is it consequential?

Wang’s claim screamed “consequential” from every angle. If China systematically develops a different type of talent than America, that’s more than an education story. It’s an economic story, a national security story, and a story about which country will lead the century we’re living in.

But first, I needed to know: Is it actually true?

Wang had credibility. He grew up in Canada and studied in the USA. From 2017 to 2023, he lived in China, where he published his observations on the country’s economy, technological development, and culture.[3] He witnessed their transformation firsthand. That gave him ethos, credibility based on direct experience. But credibility without data is just compelling storytelling. I needed numbers. Would the data back up this observation?

So I did what I always do: I went looking for the numbers.

What I found shocked me.

The Numbers Nobody Wants To Talk About

Let me show you something that should be front-page news but isn’t.

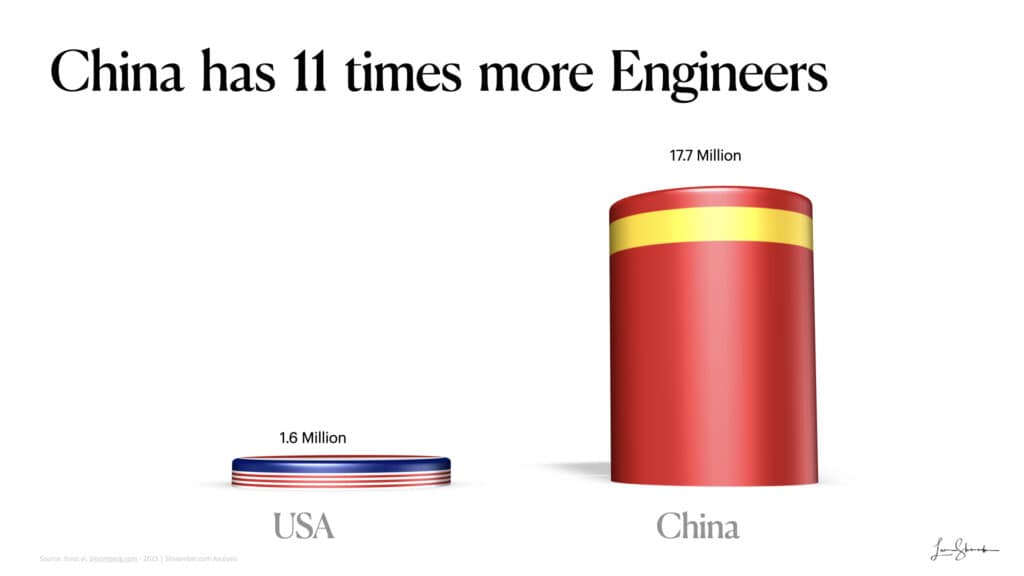

China has 17.7 million engineers. America has 1.6 million.[4][5]

Stop and absorb that.

China doesn’t have slightly more engineers. They don’t have double. They have 11 times more engineers than America in absolute terms.

“Well, sure,” you might think, “China has a bigger population.”

Fair point. Let’s adjust for population.

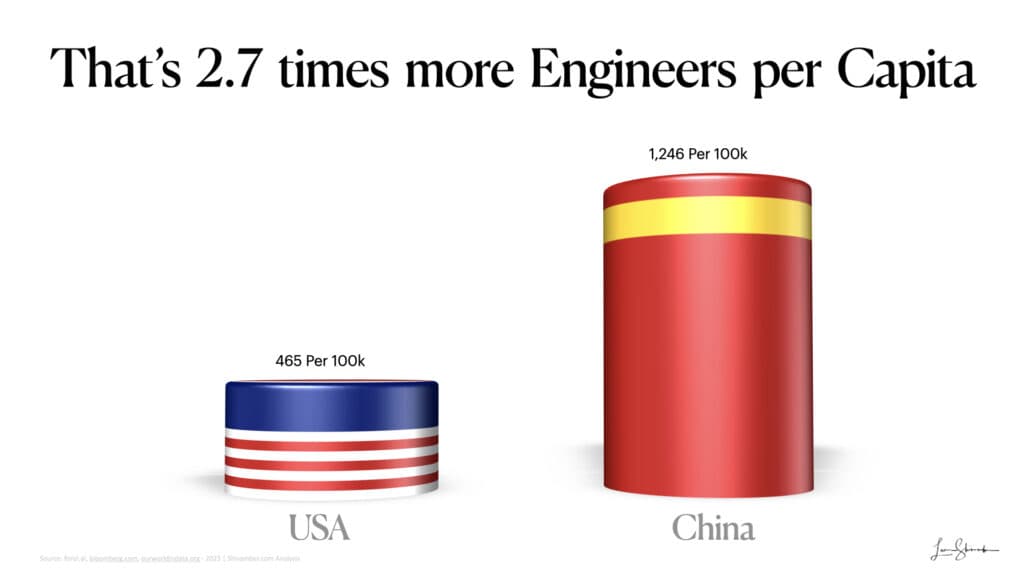

China produces 2.7 times more engineers per capita than America does.[6]

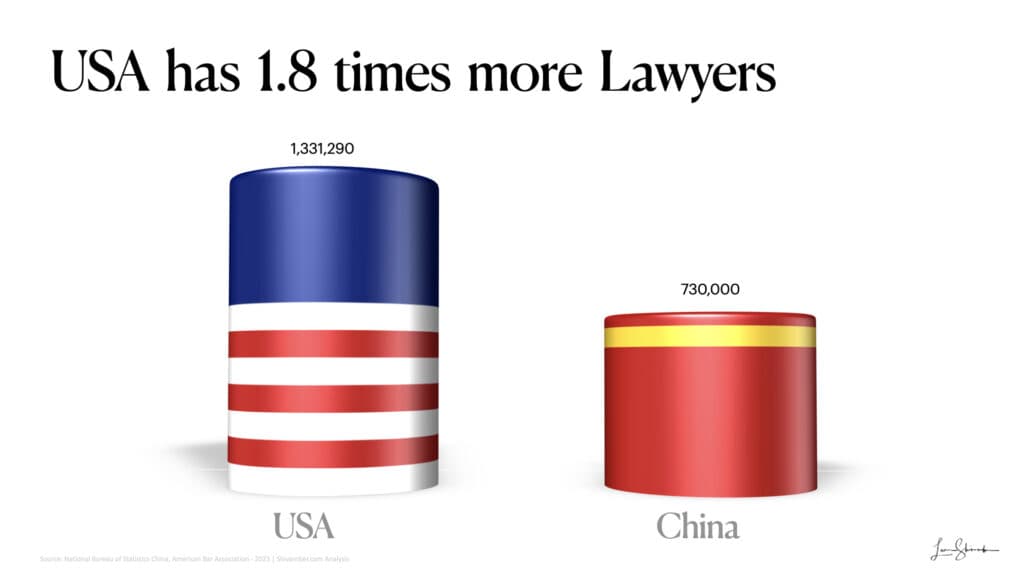

Now look at the legal profession:

America has 1.33 million lawyers. China has 730,000. [7][8]

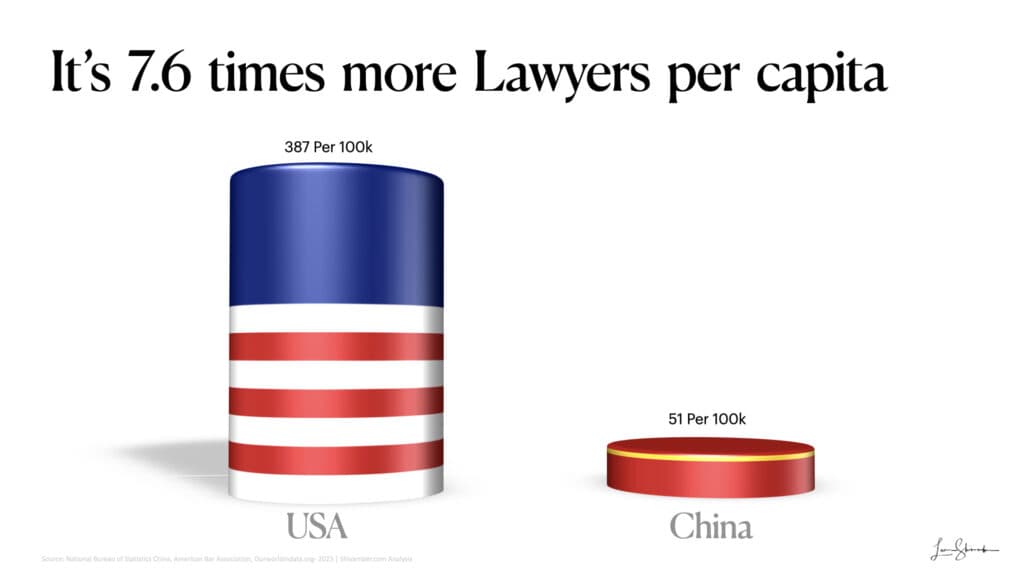

We have 1.8 times more lawyers than China in absolute numbers. But here’s where it gets interesting: Per capita, we produce 7.6 times more lawyers for every 100,000 people than China.

Let that sink in for a moment.

America produces nearly eight times more lawyers per person than China. China produces almost three times as many engineers per person as America.

We’re tilted in different directions. We are influencing and shaping fundamentally different societies.

The PhD Pipeline: Where The Future Gets Built

If you think the engineering gap is concerning, wait until you see what’s happening at the doctoral level. That’s where we can see the future of breakthrough innovation.

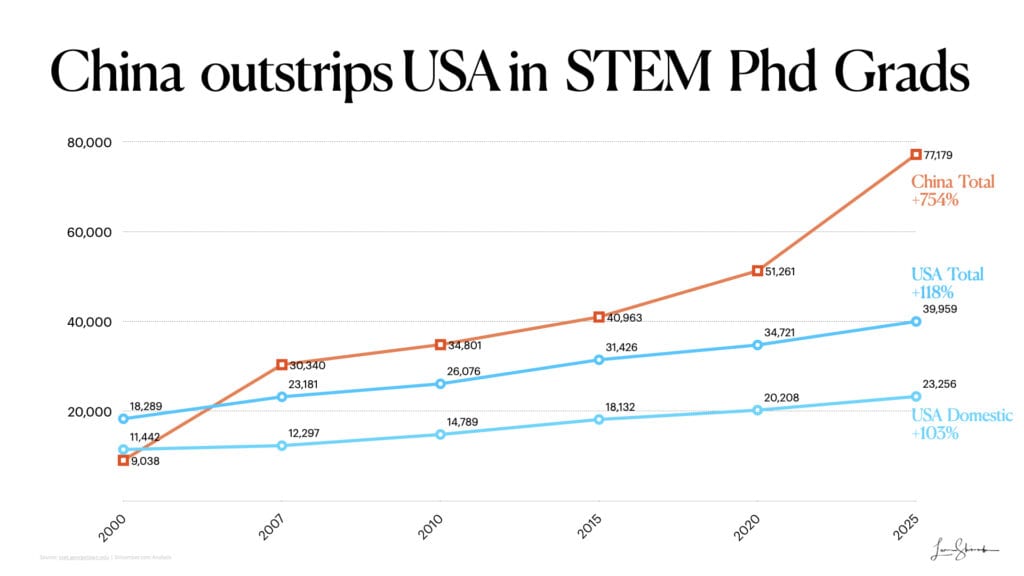

In 2025, China is expected to produce approximately 77,179 STEM PhDs, while the United States is projected to produce about 39,959, including international students who study here.[9]

China is producing nearly twice as many advanced STEM researchers as America.

But here’s the really challenging part: the trend line. Since 2000, China’s STEM PhD production has grown at a rate of nine percent annually. America’s growth rate? Just three percent.[10]

China overtook America around 2007, and the gap has widened every year since. If these trends persist, China is expected to produce three times more STEM PhDs than America within a decade.[9]

Three times more people are doing cutting-edge research in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, biotechnology, and advanced materials.

That’s not a skills gap. That’s a consequential civilizational shift.

Hold On, Here’s The Plot Twist – Quality Still Matters

Before we panic, let’s add critical context.

Not all PhDs are equal, and not all universities produce the same quality graduates. This is where the story gets more nuanced and interesting.

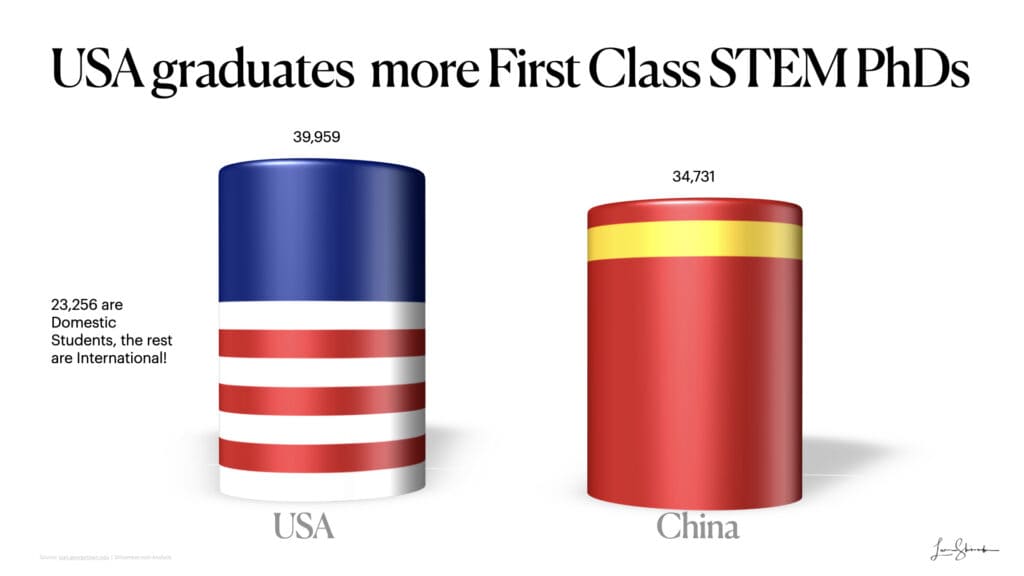

China has a tier system for universities. At the top are 42 “Double First Class” institutions, the equivalent of the Ivy League plus top public research universities.[11]

Thirty-six of the 42 universities were ranked among the top 500 universities globally, and 21 were ranked among the top 200. These elite schools produce approximately 45 percent of China’s STEM PhDs, resulting in roughly 34,731 graduates.[9]

The other 55 percent? They come from universities that would not rank in the global top 500.

Now look at America’s system. We have 55 universities in the global top 200. We hold seven of the top 10 spots worldwide.[12] Every American university granting STEM PhDs ranks well.

When you adjust for both quality and population, something remarkable emerges:

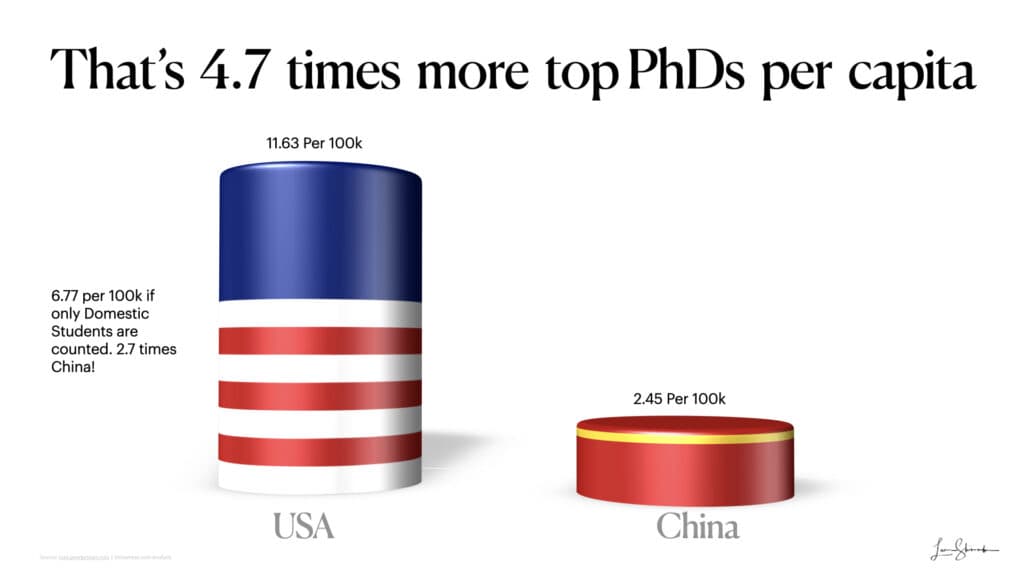

Per 100,000 people:

- US total STEM PhDs: 11.63

- China’s elite university PhDs: 2.45

America produces 4.7 times more STEM PhDs per capita than the best universities in China. Even if we only count American citizens, excluding international students, we still produce 2.76 times more than China’s top tier.

So we’re not losing the PhD race. Not yet.

But we’re losing something more important.

The Real Problem: Where Does Talent Flow?

Here’s what the data actually reveals: Both countries are educating talented people. But they’re pointing that talent in completely different directions.

America is funneling many of our best minds into law, finance, consulting, and regulatory work. Into managing complexity. Into navigating the rules around what gets built.

Both professions matter. I’m not here to bash lawyers—we absolutely need them. They protect rights. They enable commerce. They make civil society function.

But ask yourself this: When was the last time a brilliant legal argument built a bridge? When did regulatory compliance create a manufacturing ecosystem? When did litigation solve an infrastructure crisis?

The problem isn’t that we have lawyers. The problem is that we’ve forgotten how to celebrate the people who build things.

What Makers Do vs. What Regulators Do

Engineers build, design bridges, create manufacturing systems, develop new technologies, and turn ideas into physical reality.

China has over 30,000 miles of high-speed railway, more than the rest of the world combined. Terrence’s work in bringing the Olympics to China had a significant impact on this expansive strategy. In the 2000s, the country committed to building high-speed lines in preparation for the 2008 Summer Olympics. The line between Beijing and Tianjin was operating one week before the Olympics began. In 15 years, they went from zero to two-thirds of the world’s high-speed rail.[13]

In Shenzhen, I can design a new product in the morning, walk to a factory three blocks away to get the prototype made, pick it up in the afternoon, and have a revised version ready the next day. The entire supply chain, from raw materials, specialized molds, electronics, assembly, and packaging, exists within a few square miles.

An engineer in China can iterate more quickly than one anywhere else on Earth. This is not because Chinese engineers are smarter, but because they’ve built an entire physical ecosystem optimized for making things.

Meanwhile, back in America, Amtrak’s Acela, our fastest train, takes 4 hours to travel from New York to Boston, a route it has been running since December 11, 2000. While it can reach a maximum speed of 160 mph, the average speed for this route is around 66 mph.[14]

The American Society of Civil Engineers gives our infrastructure a C grade. There are 623,000 bridges in the country; 49.1% are in fair condition, and 6.8% are in poor condition.[15]

We passed a $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill in 2021, and the funds are available. But we face a workforce crisis. Twenty percent of current engineers are over 55 and headed for retirement, and we’re not training enough replacements.[16] Every year, the US will need about 400,000 new engineers.[17]

Lawyers don’t build physical infrastructure. They create legal infrastructure. They write contracts, navigate regulations, and resolve disputes, all necessary functions.

But one creates tangible economic output. The other manages the rules around that output.

We’ve tilted heavily toward the managers and away from the builders.

The Strategic Advantage We’re Squandering

Here’s the good news: America has one decisive structural advantage that has kept us ahead despite everything else.

We retain 77% of international STEM PhD graduates in the long term. For Chinese nationals specifically, that number jumps to 90 percent. [18]

Think about what that means. China educates brilliant students. They come to America for graduate school, and then nine out of ten decide to stay here permanently.

They join American companies, start American businesses, file patents in the US, teach at our universities, and become Americans.

This brain drain from China to America has been one of our most significant strategic advantages for decades. It’s one of the pillars of Silicon Valley success. It’s how we stayed ahead in technology even as our universities graduated fewer STEM PhDs.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: How long will the world’s best talent continue to choose America?

It depends on our immigration system remaining functional, our universities staying world-class, and America remaining the most attractive place on Earth for ambitious technical people.

We’re currently testing all three of those dependencies.

Why This Is A National Security Crisis

The Department of Defense has been sounding the alarm about this for years, but it somehow never gains mainstream attention.

Modern warfare isn’t merely about who has more hardware; it’s far more complex than that. It’s about artificial intelligence, cyber capabilities, autonomous systems, hypersonic missiles, and quantum computing. Every single one requires advanced STEM talent.

The DoD is one of America’s largest employers of scientists and engineers. However, it is often unable to fill critical positions because qualified candidates are not available in sufficient numbers.

Meanwhile, China’s military leverages its massive engineering talent pool to develop unmanned combat systems and battlefield AI. They’re not waiting for us to catch up.

Here’s the stat that should terrify every policymaker: China now leads America in 57 out of 64 critical technology categories.[19]

Not some. Not many. Fifty-seven out of sixty-four.

This isn’t about pride. It’s about who controls the technology that defines power in the 21st century.

This isn’t an abstract concern. It’s a national security imperative.

How We Got Here (And Why It Matters)

This didn’t happen by accident. Several forces converged over the course of decades to create this imbalance.

We glorified the wrong careers. In the 1980s and 1990s, the most prestigious paths for brilliant students led to Wall Street, McKinsey, and elite law schools. Engineering was what you did if you couldn’t get into Harvard Business School. We told an entire generation that real success meant corner offices and six-figure consulting fees, not construction sites or building things.

We made technical careers unnecessarily complex. Engineering degrees take longer to complete. The courses are more challenging, and the grading is harsher. Students graduate with the same debt as their business school peers but with fewer networking opportunities and sometimes lower starting salaries. As I’ve documented extensively, engineering degrees deliver some of the highest returns on investment; however, that message has never broken through culturally.

We stopped selling the romance of building things. We forgot to tell young people that engineers solve humanity’s most significant problems, design Mars rovers, cardiac stents, and renewable energy systems, literally shape the physical world future generations will inherit, and change lives through their work.

China made a different choice. They made engineering a national priority, celebrated engineers as heroes, paid them well, and built university systems designed to crank out technical talent at scale.

And it worked.

What’s At Stake

If current trends continue, America risks losing several critical advantages:

Innovation leadership. The countries that produce technology set the standards, shape the rules, and control the supply chains.

Economic competitiveness. Manufacturing expertise drives productivity growth. Countries that build things learn how to make them better. That knowledge compounds over time.

National security. Modern defense depends on advanced technology. You can’t defend what you can’t build. You certainly can’t maintain what you don’t understand.

Middle-class opportunity. Engineering and skilled trades provide pathways to prosperity. We need those pathways multiplied, not diminished.

Two Big Ideas to Rebalance America’s Talent

The good news? We’re not lost yet. Our universities remain world-class. When adjusted for quality, our per capita PhD production still exceeds China’s elite institutions. We retain global talent better than anyone.

But we need action. Here are the two big ideas that matter most:

1. Fix the Education Pipeline

Support STEM teachers aggressively. We have a severe shortage of physics and chemistry teachers. Millions of high school students can’t take these courses because we don’t have qualified teachers. Programs like the NSF’s Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship help, but we need them scaled 10 times.

Improve retention rates. Only 40 percent of students who start in STEM majors graduate with a STEM degree.[20] Better mentoring, paid research opportunities, and financial support would help. We’re losing talent we’ve already recruited.

Expand apprenticeships dramatically. Not everyone needs a PhD. We need skilled technicians, welders, and electricians. These roles are well-paid and critical to infrastructure. To be on par with the top 10 OECD countries, the USA would need to increase its number of registered apprenticeships from 600,000 per year to 4.3 million.[21] That’s a policy choice that requires leadership, not an inevitability.

2. Rebalance Incentives and Keep Global Talent

Make America irresistible to global STEM talent. Our 90 percent retention rate of Chinese STEM PhDs is our secret weapon. But it requires functional immigration systems, competitive compensation, and research freedom. We’re testing all three right now with bureaucratic delays and visa uncertainty.

Reduce regulatory barriers that shift talent from building to compliance. Every new regulation requires lawyers to interpret it and engineers to comply with it. Some regulation protects us. But excessive regulation shifts talent from creating value to navigating complexity. We need a rigorous cost-benefit analysis before adding layers.

Reward building over credentialing. We need to value demonstrated skills over degrees alone. Competency-based assessments enable talented individuals to advance more quickly. This will not lower standards; it recognizes that a 22-year-old who’s built three successful apps might know more than someone with a freshly minted degree and no portfolio.

What You Can Do

This may seem like abstract policy discussion. It’s not.

If you’re a parent: Talk to your kids about engineering and skilled trades as noble professions, not fallback options. Show them that building things matters. Engineering is already one of the highest ROI degrees, but we must celebrate it culturally.

If you’re an educator: Advocate for better STEM teacher compensation and training. Push for hands-on learning experiences. Connect students with mentors in technical fields.

If you’re a business leader: Create apprenticeship programs. Partner with community colleges. Stop requiring bachelor’s degrees for jobs that don’t need them. Fund STEM scholarships without strings attached. We send scouts out to find and cultivate promising athletes. Similarly, support the building of a STEM youth pipeline.

If you’re a policymaker: Streamline STEM immigration. Expand apprenticeship funding. Rigorously evaluate which regulations protect people versus which create compliance jobs. Tie education funding to outcomes.

If you’re a young person choosing a career: Consider that building things has a tangible impact. Engineering, skilled trades, and technical roles let you see your work change the world. That matters more than you think.

The Bottom Line

Dan Wang was right. China has systematically developed an engineering culture, whereas America has leaned toward regulations.

But here’s the nuance: America still has advantages. Our universities are better. We produce more high-quality STEM PhDs per capita. We attract and retain global talent better than anyone.

The question isn’t whether we’re currently behind. The question is whether we maintain these advantages.

That depends on the choices we make right now, including those regarding education funding, immigration policy, cultural values, and what we celebrate and reward.

These aren’t abstract policy debates. They are questions about what kind of country we want to be.

Do we want to be the country that builds the future? Or the country that manages what others build?

We can do both. But right now, we’re dangerously out of balance.

And in a world where China produces three times more engineers per capita, while we produce eight times more lawyers, balance isn’t optional.

It’s survival.

The makers are building the 21st century. The question is: where will they be?

Postscript

I can hear you saying, “Leon, AI changes everything. Why does any of this matter when AI can do engineering work?”

Let me say that AI only exacerbates this problem. We may not sustainably lead in AI if we don’t address the above issues. This piece is already much longer than I intended, so I will follow up on that question later.

Reference Sources

- “Terrence Burns, Chairman & CEO.” Tburnssports.Com, www.tburnssports.com/about. Accessed 31 Oct. 2025.

- “Breakneck: China’S Quest to Engineer the Future.” Danwang.Co, 25 Jul. 2025, danwang.co. Accessed 31 Oct. 2025.

- “Dan Wang: Research Fellow.” Hoover Institution, www.hoover.org/profiles/dan-wang. Accessed 31 Oct. 2025.

- Ren, Shuli. “China’s ‘Engineer Dividend’ Is Paying Off Big Time.” Bloomberg.Com, 24 Mar. 2025, www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2025-03-24/china-s-engineer-dividend-is-paying-off-big-time. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Fujiwara, Liz. “How Many Engineers Are in the U.S. in 2025?” Fonzi.Ai, 22 Jul. 2025, fonzi.ai/blog/engineers-in-us. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- “Population and Demography Data Explorer.” Ourworldindata.Org, ourworldindata.org/explorers/population-and-demography?country=CHN~USA&indicator=Population&Sex=Both+sexes&Age=Total&Projection+scenario=None. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- “Profile of The Legal Profession.” American Bar Association, www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/news/2023/potlp-2023.pdf. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- “No Time To Rest.” China Business Law Journal, 9 Oct. 2025, law.asia/china/chinese-law-firms-data-highlights-revenue-struggles/#:~:text=Has%20this%20goal%20been%20attained,(CAGR)%20of%2011.5%25. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Remco Zwetsloot, Jack Corrigan, Emily Weinstein, Dahlia Peterson, Diana Gehlhaus, and Ryan Fedasiuk, “China is Fast Outpacing U.S. STEM PhD Growth” (Center for Security and Emerging Technology, August 2021). https://doi.org/10.51593/20210018 Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Long, Trelysa. “America’S Innovation Future Is at Risk Without STEM Growth.” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF), 10 Sept. 2025, itif.org/publications/2025/09/10/americas-innovation-future-at-risk-without-stem-growth/. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Peters, M. A., & Besley, T. (2018). China’s double first-class university strategy: 双一流. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(12), 1075–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1438822

- “World University Rankings 2026.” Times Higher Education, www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/latest/world-ranking. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Alvarez, Antonio. “The Global Rise of China’s High-SPeed Rail Network.” China Today, 17 Oct. 2025, www.chinatoday.com.cn/ctenglish/2018/commentaries/202510/t20251017_800418146.html#:~:text=China’s%20economic%20ascent%20is%20often,tourism%2C%20and%20stimulating%20regional%20industries. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- “Acela.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acela. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- “A Comprehensive Assessment of America’s Infrastructure 2025 Report Card.” American Society of Civil Engineers, infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Executive-Summary-2025-Natl-IRC-WEB.pdf. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Augustine, Norman R. “The Uncapped Potential: Engineering an Opportunity of a Lifetime.” National Academy of Engineering, 26 Sept. 2024, www.nae.edu/323243/The-Uncapped-Potential-Engineering-an-Opportunity-of-a-Lifetime#:~:text=In%20many%20of%20these%20instances,will%20need%20to%20be%20replaced. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Kodey, Abhi, et al. “The US Needs More Engineers. What’S the Solution?” Boston Consulting Group, 13 Dec. 2023, www.bcg.com/publications/2023/addressing-the-engineering-talent-shortage. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Jack Corrigan, James Dunham, and Remco Zwetsloot, “The Long-Term Stay Rates of International STEM PhD Graduates” (Center for Security and Emerging Technology, April 2022). https://doi.org/10.51593/20210023

- Riggi, Justin. “How China Is Outperforming the United States in Critical Technologies.” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 23 Sept. 2025, itif.org/publications/2025/09/23/how-china-is-outperforming-the-united-states-in-critical-technologies/. Accessed 2 Nov. 2025.

- Stevens Institute of Technology. “Why Don’t Students Stick with STEM Degrees?” Phys.Org, 11 Jan. 2023, phys.org/news/2023-01-dont-students-stem-degrees.html. Accessed 3 Nov. 2025.

- McSwigan, Curran. “America’s Apprenticeship Gap in Two Charts.” Third Way, 23 Feb. 2024, www.thirdway.org/memo/americas-apprenticeship-gap-in-two-charts. Accessed 3 Nov. 2025.

Fascinating insights—thought-provoking, indeed!